By Shayla Nidever and Mary Ramsey

Over three months have passed since deadly carbon monoxide poisoning left two dead in an aged apartment complex owned by the Columbia Housing Authority.

Since then, the CHA has shuttered the 244-unit Allen Benedict Court, brought in new leadership and responded to lawsuits claiming that the lack of carbon monoxide detectors contributed to the deaths of Calvin Witherspoon, Jr. and Derrick Caldwell Roper and sickened dozens of others.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development has reacted to the deaths as well, announcing that it will soon require carbon monoxide detectors in public subsidized housing.

According to NBC News, 13 residents of public housing have died since 2003 because of hazardous gas.

According to an April 18 press release, HUD sent a notice to property owners to “remind and encourage them to install working CO detectors in their properties.” HUD also says it will propose new laws to require CO detectors nationwide.

Those new laws, HUD said, will also apply to the voucher-style housing that has largely replaced post-World War II era public housing complexes that dotted the Columbia landscape for decades. Many displaced Allen Benedict residents now reside in apartments or homes that require vouchers.

“A simple, inexpensive, widely available device can be the difference between life and death,” said HUD Secretary Ben Carson in a statement. “Given the unevenness of state and local law, we intend to make certain that CO detectors are required in all our housing programs, just as we require smoke detectors, no matter where our HUD-assisted families live.”

HUD did not offer a timeline for when the new rules would be officially proposed or implemented.

Executive director Gilbert Walker announced his retirement shortly after the deaths and emergency evacuation at Allen Benedict, and the authority’s board has not yet named a successor.

CHA is also working to clean house after the deaths of Witherspoon and Roper.

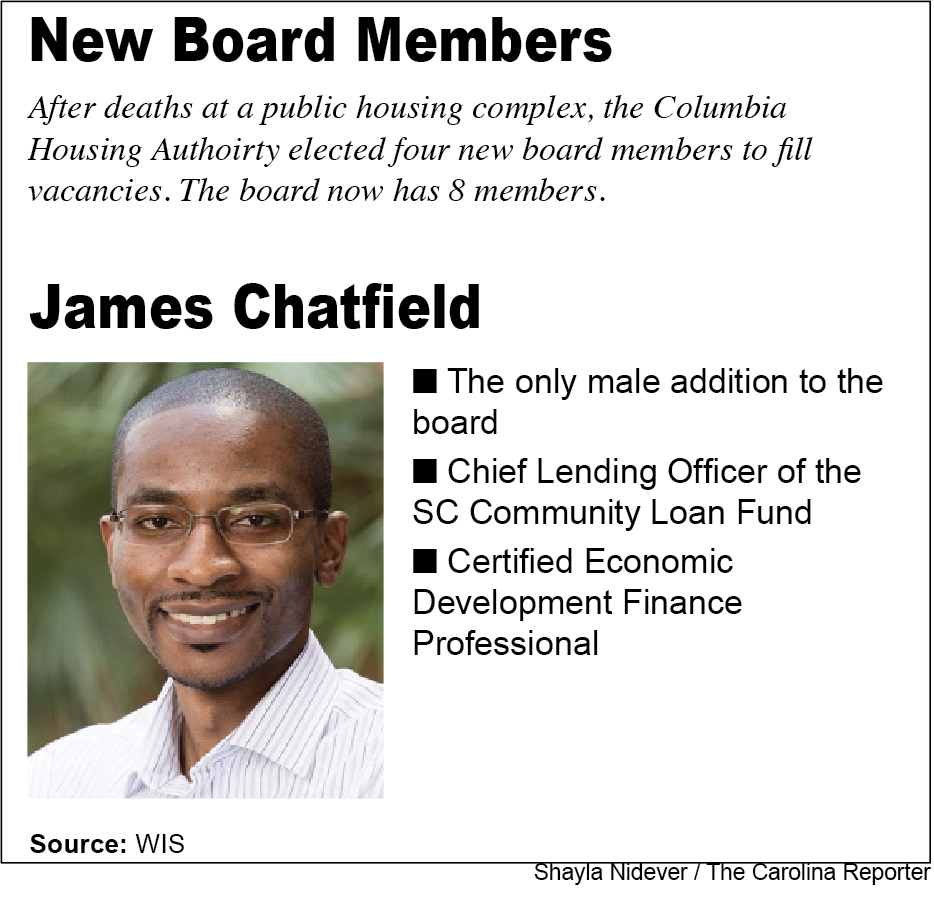

Four new board members were appointed by the Columbia City Council last month. James Chatfield, Georgia Mjartan, Kara Simmons and Anne Sinclair began serving as the newest members on March 5. Of these new board members, none are residents of public housing, something that doesn’t sit well with Columbia lawyer Hemphill Pride.

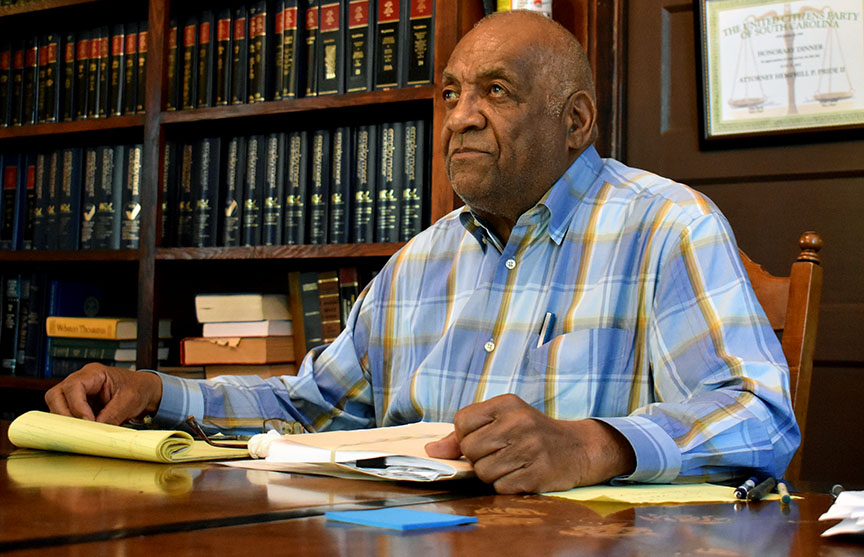

“My point about the agency … It was not run to the benefit of the residents. They elected a new board and didn’t even consult with the damn residents,” he said.

Pride is representing a couple that lived at Allen Benedict Court. After having to evacuate their home in the middle of the night, Pride’s clients lived in a hotel for a “considerable period of time,” and have finally found a permanent residence using a voucher.

The lawsuit is pending, but Pride is adamant in his pursuit of holding the CHA accountable.

He said the newest failure of the organization, which Pride called a “cash cow,” is the election of a board that does not reflect the community.

Pride’s clients are paying more for the second-story duplex they currently live in than they paid at Allen Benedict. The stairs they climb to get to their home are causing more problems for them, as the wife is overweight and husband has cancer among a slew of other medical issues, he said.

Many former ABC residents, Pride says, are struggling financially while the organization profits.

“If that’s the plan over there, I’m going to adamantly oppose that by any means necessary. That’s how strongly I feel about that,” said Pride.

Pride, who spent time around the historic public housing complex when it was a Columbia institution, is looking for holistic change within the organization.

“A perfect world for me would be for people in authority and that have power to realize that we’re judged by how we treat the least of us, and keep that in the forefront at all times,” said Pride.

Multiple former residents have also signed onto a class action suit.

Columbia attorney Ron Cox represents the two named clients in that case, former Allen Benedict residents Tammy Basinger and Khaylis Scott.

“There are several different legal theories that are advanced in [the case], but they all revolve around the same thing, which is that the housing authority didn’t live up to its obligations to provide habitable living conditions,” he said.

Cox is optimistic that the class action case will not only help the displaced residents of Allen Benedict but also bring awareness to other failures in the public housing system.

“Certainly I hope that this suit, and the issues that occurred with Allen Benedict, will lead to some change and reform in the housing authority so they can provide better services to everybody,” he said.

Still, Cox stressed that, based on his experience, it will take time for the suit to move through the courts.

“It would not be unusual for the case to play out over a period of months and maybe even more than a year.” he said. “That wouldn’t be unusual at all. It’s not something that’s expected to necessarily come to a quick resolution.”

The CHA did not respond to requests for comments. There are currently no public plans regarding what will happen to the vacant housing complex, which has sat empty for months.

In numbers recently shared by WLTX, 26 families are still displaced.

Columbia attorney Ron Cox is representing two displaced residents of Allen Benedict Court in a class action lawsuit against the Columbia Housing Authority.

Apartment N9 in Allen Benedict Court, a housing complex that was evacuated in the middle of the night, shows a few remaining personal touches and a notice reading “NO TRESPASSING.”

Months after hundreds of residents were abruptly displaced from Allen Benedict Court after two men died from gas leaks, children’s toys and household items still sit outside the vacant buildings.

Hemphil Pride, a lawyer native to Columbia, has a suit against the Columbia Housing Authority that is still pending.