A crumbling church in Hampton County.

Seemingly endless fields of cotton and bare land where trees once stood tall. Houses crumbling under their infrastructure, with caving roofs and overgrown yards. An agricultural and lumber-based community plagued by poverty, divided by race.

The rural Lowcountry of South Carolina is home to tens of thousands of people, and the lack of industry affects all aspects of life and all ages. Driving through the Lowcountry, you won’t see big box stores, but rather abandoned buildings with shattered windows, a haunting reminder of the life that once existed.

Transporting Industry to the Rural Community

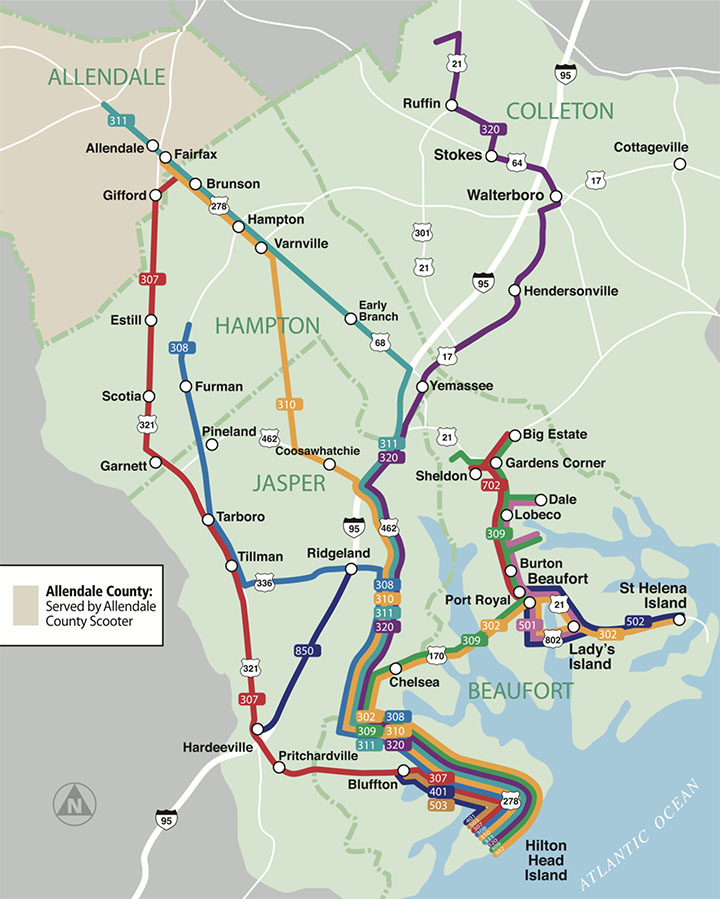

Each morning, starting at 4:30 a.m., a Palmetto Breeze bus shuttles rural residents to where there is work. The passengers arrive on picturesque Hilton Head Island between 6:15-6:45 a.m. and are dropped off at vacation resorts where they work in the service industry. There are also stops in Beaufort for the same reason. Then, in the evening, there are bus trips back home to the rural communities.

The Palmetto Breeze Transit has multiple routes to transport workers from rural Lowcountry areas, like Allendale, Colleton, Hampton, and Jasper counties, to Hilton Head Island to work in the resort service industry. Credit: Palmetto Breeze Transit

Industry and School Funding

South Carolina’s K-12 education system has been under national scrutiny for decades. Many are critical of the educational standard of minimally adequate. The struggle for high-quality schools for all the children in the Palmetto State continues, especially in rural areas. Poverty and lack of industry go hand in hand, factors that have a detrimental impact on school funding. Businesses are taxed and have been left paying a larger share of the cost of operating the schools. There’s also a higher sales tax. But in rural areas where there are no jobs and no stores to shop to collect those taxes, how are the schools getting the money they need to operate?

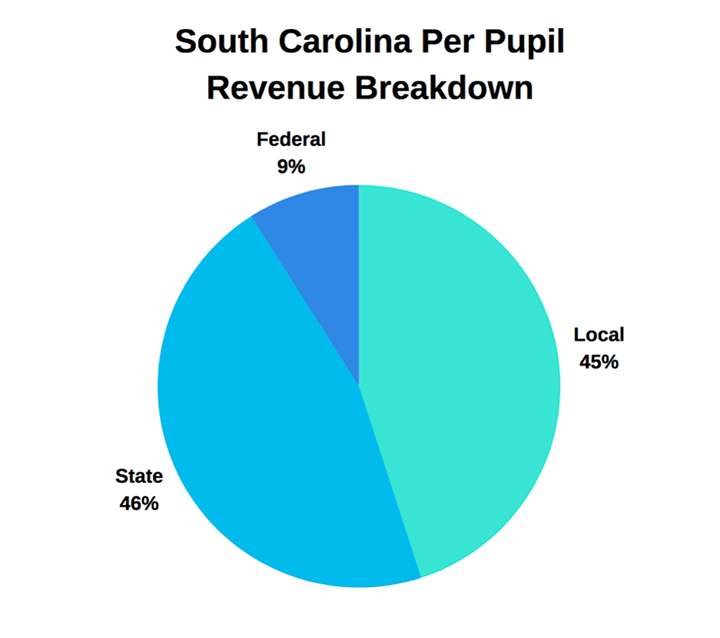

The standard measurement for school funding in South Carolina is per pupil revenue. However, it only covers operational costs, like turning on the lights, hiring teachers and principals. Nearly half the per pupil revenue comes from the local economy, but the state supplements areas with high poverty. That’s why some poor counties have higher per pupil revenue than wealthy counties. For example, in the 2016-2017 fiscal year, Hampton School District Two got $18,689 per pupil, with the Poverty Report Card Index reporting it at 90% poverty. McCormick County School District was funded at the highest in the state as a rate of $20,173 per pupil with 81.68% poverty. By comparison, Dillon School District Three only received $9,144 per pupil with 69.83% poverty. But there’s a catch when it comes to how schools can spend that money.

South Carolina public school funding breakdown. Per pupil revenue covers operational costs only, such as turning on the lights and hiring teachers and principals. It does not include building maintenance or technology.

“When I’m talking about these per pupil revenues, it does not include debt service, it doesn’t include building buildings, it doesn’t include repair to buildings, it doesn’t include maintenance,” said Melanie Barton, the executive director of South Carolina’s Education Oversight Committee. “That is generally a local issue, that’s where a lot of the disparity has come from, is that locals may not be able to generate the money to build a new school or address some of the structural problems especially if they are a small district where the tax base is very small, so that’s an issue for school districts the financing of structures.”

Interactive Map – mouse over the map to view statistics on poverty levels and teacher info for elementary schools.

In rural areas it’s also hard to find teachers for the classroom. If you look at the numbers in the map above, teacher salaries are lower where poverty levels are higher. But look where there are jobs. That’s where teacher pay is higher and so is the revenue stream. Beaufort County School District is able to offer a $5,000 signing bonus because it can keep the taxable income from Hilton Head’s tourism industry. That money then pays for new construction and most classrooms are brimming with technology. All students in third grade and above have laptops. Kindergarten to second grade students have personal iPads. Even though there are large pockets of poverty, the schools are well funded, buildings new and filled with technology. In areas with little to no industry it is difficult, if not impossible to update schools. Instead many schools in impoverished areas go without repairs. That’s the case in Hampton School District One were many of the buildings are nearly 70 years old.

“Most of our schools are old and we have to work constantly and be on guard constantly or they are going to deteriorate to an environment that is not conducive to learning,” said Ronald Wilcox, superintendent of Hampton School District One.

Dilapidated air conditioning units outside of classrooms at Varnville Elementary School in Hampton District One.

Struggles of the Rural Teacher

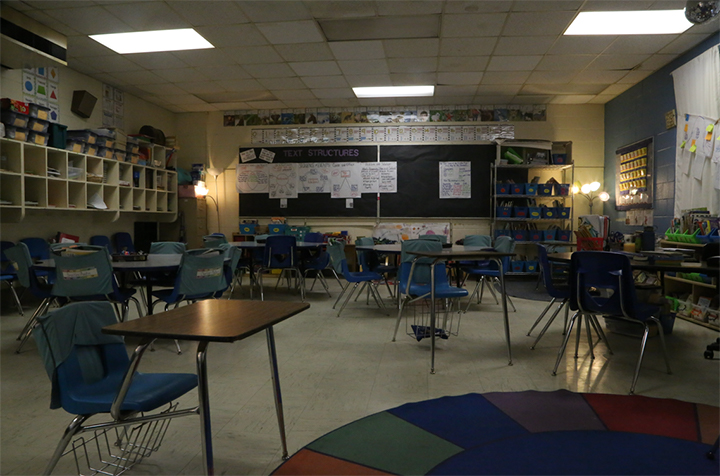

Just minutes after the last school bus pulled away at Varnville Elementary School in Hampton School District One, the school hallways were quiet and dark. By lamp light, second grade teacher Amber Marshall sorts through papers, preparing for tomorrow’s school day. Marshall noted that the teachers have made a conscious effort to turn off hall and classroom lights after the students leave to save on electricity costs. The money saved either goes to other schools in Hampton One who went over budget, or is distributed back to teachers at Varnville Elementary to purchase more classroom supplies.

In some years, teachers at Varnville have an extra $200 to buy classroom supplies. However in the 2017-2018 fiscal year, the money was given to schools in Hampton One School District that did not meet budget. At the beginning of each school year, every teacher is given a stipend of $275 to purchase items for their classroom such as organizational supplies, office supplies, chart paper, dry erase markers, pens, and a text set for the classroom. Teachers are expected to buy books for the classroom, and often times the stipend doesn’t stretch enough to fill their in-class libraries. With hungry readers, ready to devour new content that they can’t get at home, teachers are expected to fill their libraries with an array of books at all different reading levels. They scour through old classrooms, yard sales or books that libraries are getting rid of, but still their libraries need more.

Amber Marshall’s second grade classroom at Varnville Elementary School. Marshall noted that teachers try to keep the lights off after students leave to help save on electricity costs. The money saved either goes to other schools in Hampton District One that are over budget or to purchase more classroom supplies.

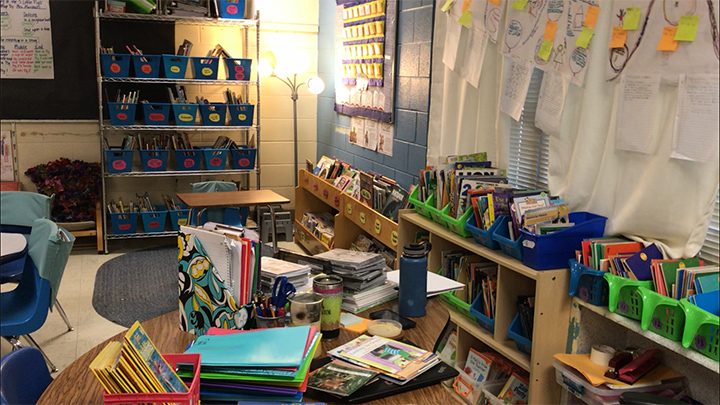

“I opened up an Amazon credit card and I just went ahead and spent like 900 bucks, put that on the credit card and maxed it out, for those books,” said Amber Marshall, a second grade teacher in Hampton One.

Marshall likes to keep a well-stocked library, so her students always have something new to read at their level. She said it can be difficult as her students reading levels range from B to S on the Fountas and Pinnell reading levels. Books at a the lower level B range are filled with illustrations and repetitive patterns, while upper level texts in the S range are more complex, they require the reader to understand the text and make inferences beyond the text itself. Marshall said that more than half of the students in her class read below a second grade level. Finding ways to provide adequate reading materials for students is just one of the many hidden costs of being a teacher in rural Lowcountry South Carolina.

Marshall’s in class library, which she purchased with personal funds.

The Fight for Adequate Funding: Abbeville County School District v. State

The fight over education funding goes back decades in South Carolina. In 1993, 40 school districts of the state’s then 91 districts banded together to sue the state seeking equity in education funding for the poorest, rural schools. In Abbeville County School District v. State of South Carolina, the school districts challenged the equal protection clauses of the state and federal constitutions, claiming that the statutory “scheme” of public funding for education lacked uniformity and imposed unlawful tax burdens on the school districts. They argues this resulted in a disparity in educational opportunities for students throughout the state, with schools in impoverished areas not being funded at the level mandated by the Education Finance Act (EFA) and the Education Improvement Act (EIA). Circuit Judge Thomas W. Cooper Jr. argued that under the South Carolina Constitution, the General Assembly had an obligation to provide a system of free public schools. Cooper realized that when the lawsuit was filed in 1993, there was no qualitative measurement for education, and he dismissed the case. The case made its way to the South Carolina Supreme Court where, in 1999, the justices developed the “minimally adequate” standard to provide a qualitative measurement for education.

“We hold today that the South Carolina Constitution’s education clause requires the General Assembly to provide the opportunity for each child to receive a minimally adequate education.”

The minimally adequate standard:

- the ability to read, write and speak the English language, and knowledge of mathematics and physical science;

- a fundamental knowledge of economic, social, and political systems, and a history of governmental processes; and

- academic and vocational skills.

Abbeville II

Twelve years later in 2005, Circuit Judge Thomas Cooper Jr. ruled in the case. In the court’s decision, it states that students in South Carolina school districts were not receiving the constitutionally required educational opportunity, but only because of “the lack effective and adequately funded early childhood intervention programs designed to address the impact of poverty on their educational abilities and achievements.” Cooper found that other aspects of the public school system, including teacher quality and facilities, were minimally adequate.

The playground at Varnville Elementary School in Hampton District One. The majority of the items in the playground were covered in rust.

Act 388

In 2006, while this case was in limbo, state lawmakers made a move that had a major impact on education funding. They approved Act 388, which swapped a portion of property taxes for a 1-cent increase in state sales tax, redistributing funding for education. They also increased taxes on businesses, including hotel tax levied to state tourists.

This impacted school funding across the board. Beaufort County School District was able to maintain steady funding, since they could benefit from the increased hotel accommodations tax at the Hilton Head resorts and elsewhere. But areas with few or no hotels or other businesses were hurt by their inability to generals tax revenue.

Abbeville II Continued

Meanwhile, in 2008, the landmark court fight over funding in South Carolina’s schools had moved to the state Supreme Court. But it wasn’t until 2012, when lawyers on both sides made their case before the justices. The state’s highest court issued a ruling in favor of the districts in 2014.

The justices also found the entire public education system to be constitutionally lacking and ordered the General Assembly to remedy the situation. After the consolidation of some school districts, some also received a payout to help bring their districts up to the minimally adequate standard. But in 2017, the court reversed the decision, stating that Abbeville II was wrongly decided as it was a violation of the separation of powers. The South Carolina Supreme Court, under a new chief justice, believed that it was not within the court’s power to modify the educational system.

The justices believed that anything regarding the South Carolina education system should be handled by the General Assembly. The decision is leaving some school officials wishing for more.

“The legislature ruled that the Abbeville case, that they had done their part that they had fulfilled their obligation according to the intent of the case, so to speak and that we wouldn’t be receiving any more funds,” said Wilcox, the Hampton District One school superintendent. “And I wish they would continue to give us some funds for a few years until we were able to get the schools fixed up because not only is our school district in need of funds there are other districts in the Lowcountry that needs these funds as well.”

Now it is up to Gov. Henry McMaster and the General Assembly to make any decisions regarding the quality of education that is being provided to students across in the state of South Carolina. While the court battle is over, the debate continues as lawmakers make K-12 education the top priority of the 2019 session.