The body of former U.S Sen. Ernest “Fritz” Hollings lay in repose at the S.C. State House Monday. He died last week at the age of 97.

Bright. Bold. Blunt.

That’s how former S.C. Rep. James Felder remembers Ernest “Fritz” Hollings, the former U.S. senator and South Carolina governor who died April 6 at the age of 97.

“I remember him as a great statesman; he spoke his mind,” said Felder, president of the SC Voter Education Project. “South Carolina is better today because of Fritz Hollings, singlehandedly.”

Hollings’ body lay in repose Monday on the second floor of the S.C. State House, where his Democratic colleagues along with ordinary South Carolina citizens passed by his flag-draped coffin to pay their respects and remember a man known for his progressive, bipartisan politics and loyalty to South Carolina.

“That’s the way it ought to be. A man who lived the kind of life he did and did the kind of things he did needs to be remembered,” said Gov. Henry McMaster, who unsuccessfully challenged Hollings in 1986 for the U.S. Senate seat Hollings won in a special election in 1966.

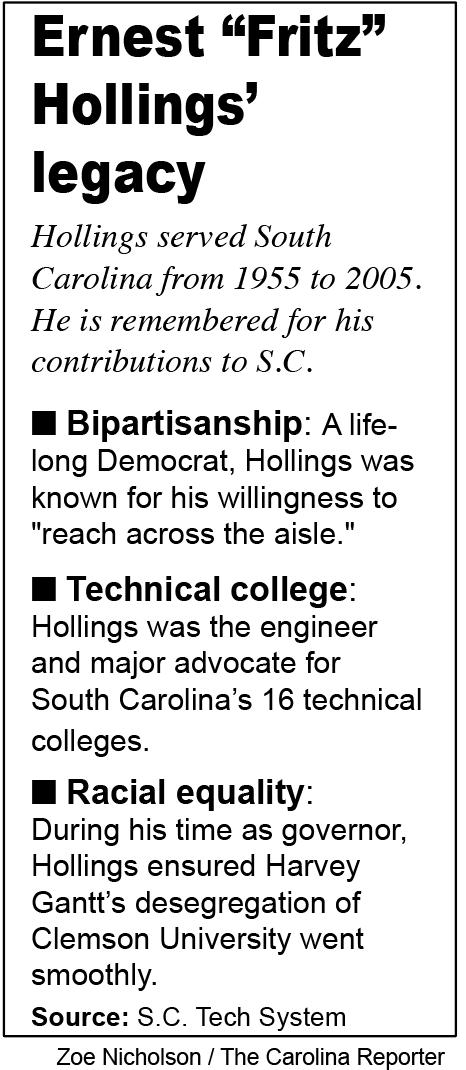

Hollings, a native Charlestonian, served as a state representative, lieutenant governor and governor at the mid-point of the 20th century before being elected to the U.S. Senate. He won six full terms, retiring in 2005 after 38 years.

“He believed in government, and making the government work for the benefit of the people,” Jerry D. Pate of Columbia said of Hollings.

Pate worked as a lobbyist for years, and said he “called upon Senator Hollings” often during the Democrat’s time in the Senate. Pate, who is also a former State House reporter, emphasized Hollings’ willingness to work across the aisle.

“He [Hollings] worked across the aisles. He thought that it was important to talk with everyone in order to get projects done, unlike today where there is so much partisan bickering,” Ralph Everett of Alexandria, Virginia, said. Everett was the former chief counselor and staff director of the Senate Commerce Committee, of which Hollings was the chair for 13 years.

Aubrey Davis, who worked as a staffer for the Senate Commerce Committee with Everett, said Hollings’ brand of politics is a rarity.

“He’s a bit of a vanishing breed, in that he had the capacity to work with Republicans as well as Democrats. Unfortunately, things have become more polarized since he was in the Senate,” he said.

Hollings used his time in the Senate and as governor to promote industry, tourism and education in South Carolina. Hollings is credited with creating and advocating for the South Carolina technical college system. He embarked on a hunger tour of his native state in 1968, finding pockets of such deep poverty and malnutrition that he created a national war on hunger, instituting such programs as the Special Supplemental Food Program for Women, Infants and Children, or WIC program.

Don Fowler, a USC professor and former Democratic National Committee chairman, said Hollings’ hand in technical education was one way he helped to “transform South Carolina from a pre-World War Two state to a modern state.”

“I’ll always remember him as a senator who put education first,” Felder said.

Hollings, who began his career as a segregationist, evolved in his politics, insisting that South Carolina turn its back on the old segregationist past and integrate without violence. When a federal court ordered Clemson University in 1963 to admit Harvey Gantt, a black Charlestonian, Hollings told the legislature, “We have run out of courts.”

“He went on to explain that we would not have, here in South Carolina, the kind of violence and disturbances that they had in Alabama and other places,” Fowler said.

Felder worked with Hollings to register black South Carolinians in the 1960s, and got Felder’s blessing to vote “no” on Thurgood Marshall’s nomination to the Supreme Court in order to win reelection.

“He [Hollings] reminded me that a majority of white South Carolinians had not forgotten Marshall’s role in Briggs v. Elliott,” Felder said. Briggs v. Elliott was a 1952 South Carolina case that challenged segregation in the public schools. The Briggs case was joined with four others to become the landmark 1954 U.S. Supreme Court case that overturned segregation in public schools. Marshall argued the case in South Carolina and before the Supreme Court.

“He won his reelection and became a progressive voice for South Carolina,” Felder said.

Hollings’ legacy morphed from a conservative Democrat to a progressive one during his nearly 40 years in the Senate.

“He made decisions based upon his conscience, not politics,” Katrina Riley of Summerville said.

Hollings was known as an outspoken family man, who enjoyed spending time with his children and grandchildren.

“I would talk to Senator Hollings at least once a month after he retired,” Everett said. “We always laughed, talked about family, children, grandchildren. And that was very important to him.”

McMaster remembered Hollings’ commitment to family.

“Politics is a part of life, but it’s not all of life,” McMaster said. “He’s among the best of us.”