Sani Abacha, the late Nigerian Army officer and politician accused of stealing funds from his country, is the face of scamming and his picture is often used in memes about fraud. His name, along with those of his wife and son, are frequently used in Nigerian Prince scams.

Steffi Marti, a student at the University of South Carolina, knew the email she received in September seemed a little fishy. But looking to make money to supplement her student budget, she answered it and almost fell victim to a notorious scam targeting college students.

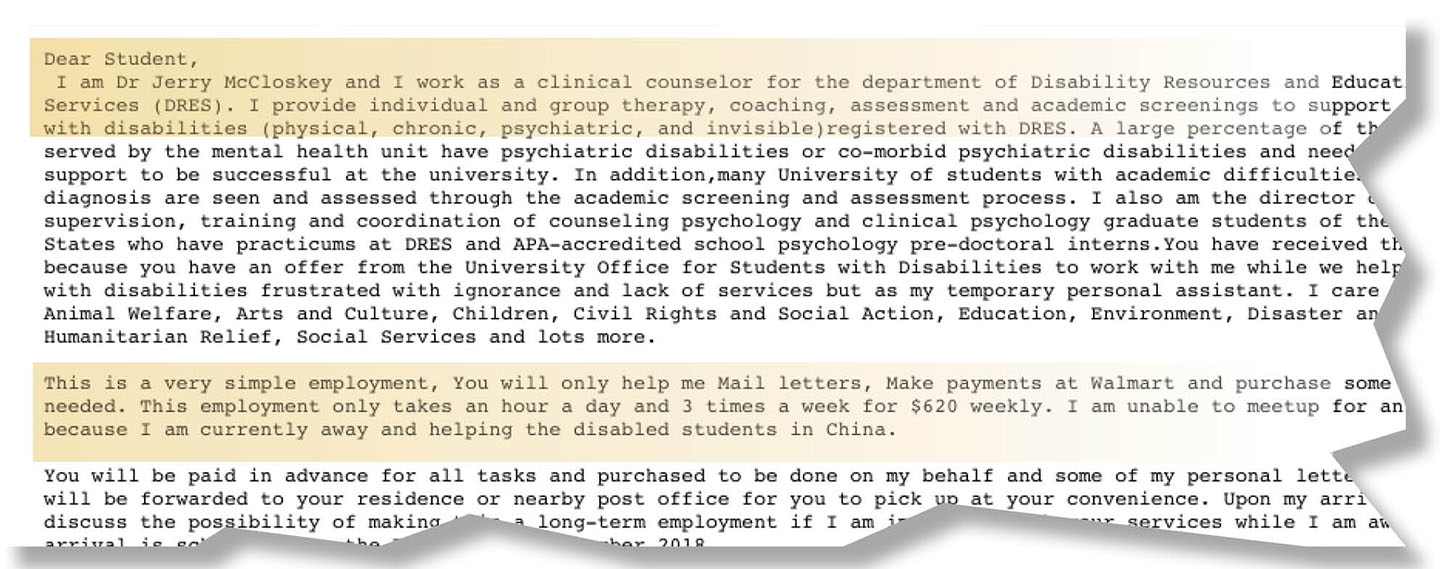

The email from a man who called himself Dr. Jerry McCloskey offered a quick way to earn money: “This is a very simple employment, you will only help me mail letters, make payments at Walmart and purchase some items when needed. This employment only takes an hour a day and 3 times a week for $620 weekly.”

The man who posed as a doctor said he worked as a clinical counselor for the Department of Disability Resources and Educational Services and would be unavailable to meet in person for an interview because he was helping disabled students in China.

Marti said the email sounded odd, but it was “enticing” for a full-time college student in need of an income. So, she replied.

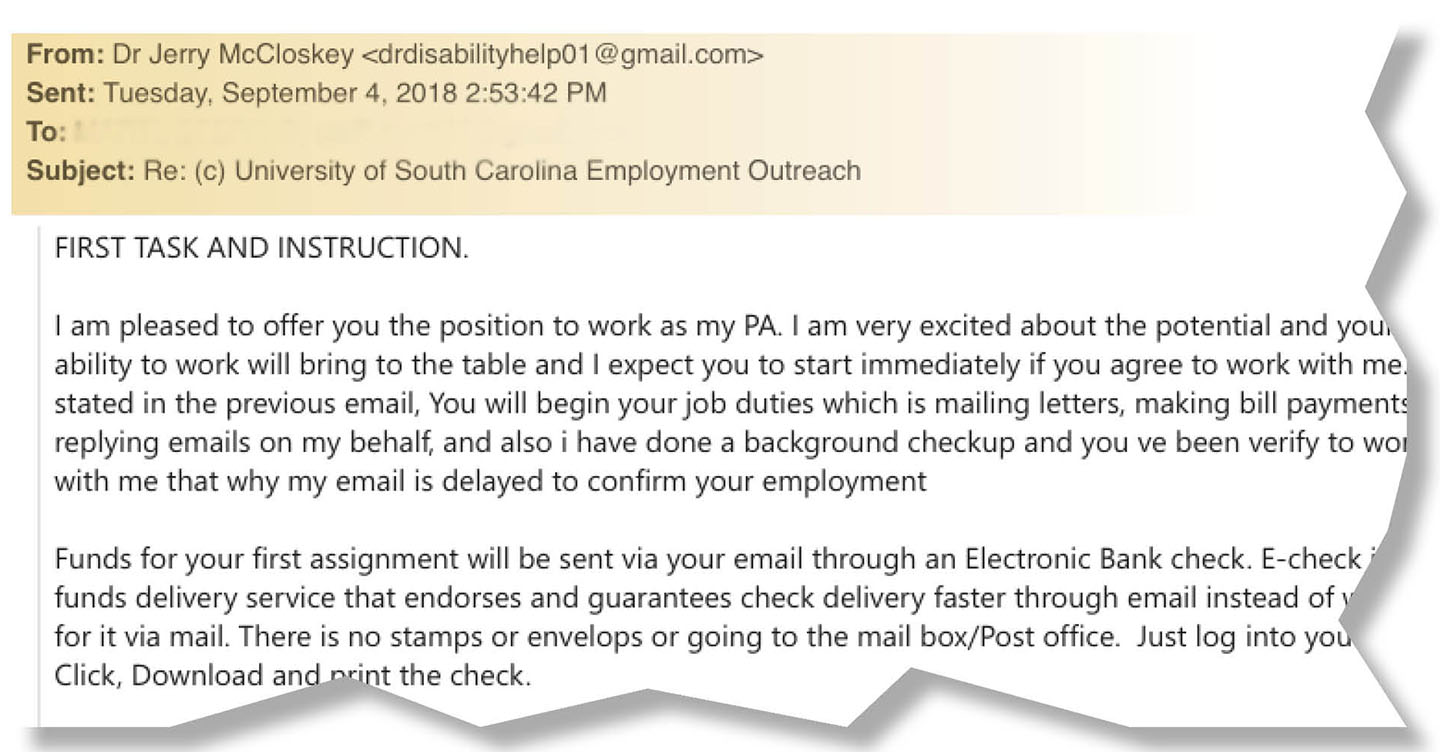

“Almost instantly I got an email back, saying how he had already run a background check on me, and I was cleared and ready to start working,” Marti, a senior majoring in global supply chain and risk management, said. “He also sent a list of things I had to do for my first assignment.”

That list included purchasing business check paper for printing an electronic check, which would be Marti’s first form of payment from her new employer.

According to the email instructions she received, after Marti bought the paper and printed the electronic check, she would then deposit the check in her bank. The check would appear to go through, and the funds would show up in her bank account in about a day. After she completed this, he would send her the next round of instructions, the fake Dr. McCloskey said.

It wasn’t until Marti went to Office Depot to fulfill her first task that she realized she had fallen for an email scam.

“You know this is a scam, right?” Marti recalled the Office Depot employee telling her. “We’ve had, like, 20 students come in for checks.”

Job offer scams are blowing up across college campuses, and they all follow a similar script. Had Marti not been warned and followed through on her task, the next email from her employer probably would have instructed her to wire money to a specified address.

The money most likely would’ve been for an item, like a laptop or expensive office supply costing several hundred dollars, needed to perform her new job, and Marti’s employer would’ve ensured her that she’d be reimbursed. Then, she would’ve discovered in about a week—most likely in a call from her bank —that the check had bounced and she had lost the wired money and perhaps set herself up for identity theft.

Unlike Marti, some students were not informed of the fraud until it was too late. The scam was sent out to students in early September of this year, and within weeks two unnamed students had lost $2,600, according to the USC Police Department.

Genesis of scamming

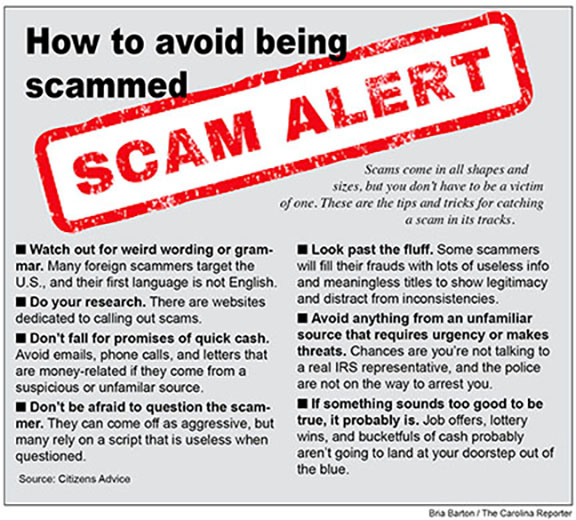

Anyone with online accounts, whether business or personal, knows not to befriend a “Nigerian prince” or any other royal who suggests he has a windfall to share with you.

The “Nigerian prince” scam is the forefather for all things spam-related and the god of all spammers past, present and future.

He dates back to the 1500s, long before the internet era, when scammers posed as a Spanish prisoner, a wealthy aristocrat locked up in Spain pleading for help and money for freedom through a middleman. In return, the person who assisted would be rewarded with some of his great fortune.

As technology became more and more advanced, so did the complexity of the scam and its effects on victims. The Spanish prisoner con job transformed into the Nigerian prince scam, also known as the advance-fee or 419 scam.

The scam emphasized the benefits of paying a little to get a lot, and its first modern usage was a newspaper ad placed by a 14-year-old boy posing as a Nigerian prince in the early 20th century.

The prince touted the benefits of friendship and lined up a number of pen pals, and then asked them to send him four dollars and a pair of pants. In return, they would be sent riches from his country.

The money and the pants were sent, but the riches never came. However, the seed that was planted inspired generations of fraudsters, which has evolved into a web of deception where everyone is now a target.

From chain-letters to phone calls and emails, scammers are utilizing every method of communication in attempt to defraud. Many people involved in the scams are unknowingly funding criminal organizations and illegal activities.

Imposter scams are one of the most widespread, and according to a S.C. Department of Consumer Affairs report, they made up 68 percent of the scams reported in the state in August.

Imposter scammers pretend to be a trustworthy source, like a neighbor, government agent, or professor, so that they can convince you to send them money. The scammers who targeted Marti combined the imposter scam with a job offer, a combination that can have disastrous effects on a student’s new credit and bank account.

According to Michelle Foster, USC’s executive director of IT communications and governance, scammers “can come from anywhere,” which is why they can be extremely difficult to track down. But much cyber-crime can be traced to developing countries, where access to technology is progressively growing.

Scamming has become so widespread that underground organizations, like the Nigeria-based Yahoo Boys, a group known for hacking and targeting Yahoo accounts, have resulted in its members amassing fortunes and glamorizing fraud through the creation of rap songs detailing their crimes.

There are even India-based call centers that exist just for the purpose of scamming, and they rely on Americans’ fear of tax season and the IRS to accomplish fraud.

And while many scams are easy to execute with just an email or phone call, some scams can last years. Scammers have learned to hone in on feelings – like trust, fear and even love – that make people respond to their requests. Some scammers go so far as to develop relationships with their victims, often taking advantage of the elderly as they slowly drain their bank accounts.

There are hundreds of online campaigns on crowdfunding sites like GoFundMe to assist victims of scams. Many of the campaigns are created by the children and grandchildren of victims, who are hoping to raise back the funds their loved ones lost.

But individuals aren’t the only targets of scams. It takes just one employee to fall for a scam and corrupt a business’s financial security. According to the FBI, a scam cost a South Carolina business $350,000 after a Business Email Compromise scheme, a form of fraud that tricks an employee in to directing funds to a criminal bank account.

In December 2017, S.C. Attorney General Alan Wilson announced a $586 million settlement with the Western Union financial services company.

The settlement alleged that “fraudsters were able to use Western Union’s money transfer system to get payments from their victims, even though the company was aware of the problem and received hundreds of thousands of complaints about fraud-induced money transfers…”

The settlement also requires Western Union to create and implement an anti-fraud program to help detect and prevent incidents of fraud.

“Con-artists are always coming up with ways to trick people out of their hard-earned money,” Wilson said. “A wire transfer cannot be tracked to be returned to the original sender if it is found to be a scam, which is why it is often the preferred method of transferring funds for a con-artist.”

Universities become targets

Universities all over the world are prime hunting grounds for scammers because their databases not only contain personal information but also financial and academic information. In fact, Iranian hackers have targeted about 50,000 American university professors and hundreds of universities worldwide since 2013 in attempt to steal academic research.

In 2017, Coastal Carolina University was targeted by sophisticated scammers posing as vendors contracted by the school. By the time the theft was discovered, over $1 million had been stolen.

That same year, USC was targeted by malicious emails more than 100 million times. These emails are known as phishing, a tactic used to gain personal information by posing as a reputable source, for example – like in Marti’s case – a doctor.

“Phishing emails are the cheapest and easiest way for an attacker to get access to a user’s account and their data. All the attacker has to do is send an email,” Foster said.

Foster says that when someone is a victim of a phishing attack, their account is often compromised by the attacker so that they can send even more phishing messages to others.

As a result, emails that are from an internal address are not marked as spam and are more likely to be delivered than a message from an external email address.

Although USC has an advanced filtering system in place for these emails, some manage to sneak by, which can wreak havoc on an individual’s personal information and finances if they fall victim to the scam.

“Attackers can also ‘spoof’ email addresses. They make it appear that an email came from an internal address, when it actually did not,” Foster said. “Most attackers are very familiar with email filtering systems and use techniques to try to bypass them. Unfortunately, they often succeed.”

While scammers have recently been posing as professors and job recruiters to gain students’ trust, phone scammers impersonated the police and targeted international students at USC with threats of arrest and deportation if they did not pay thousands of dollars to the IRS in 2014.

“[They] typically do the following: create a since of urgency, like ‘you have four hours to respond.’ Or something bad will happen if you do not do this, like ‘you will not receive your package, you will no longer have access to your email account, you will get arrested if…,’” Foster said.

Earlier this year, Ruben Conyers Jr., a USC student, was the target of a summer internship phone scam, which promised him opportunities to travel and earn big wages.

He says that he initially agreed to it, but upon further investigation of “fake” positive reviews of the company, he found Reddit threads and websites dedicated to the horror stories of students that had fallen for the scam.

“I was rolling with it until I did my research some more, and it was saying this is a scam, and you’re going to have to worry about where you’re going to sleep at night,” Conyers said. “[If I had taken it], I’d probably be somewhere stuck in a whole other state with no way back home.”

Other students like Ayana Scriven has been targeted by scammers through email but never responded to them. She received a job offer from a professor in Colorado, and like Marti, she says the email sounded weird, but a job opportunity was worth looking into. So, before responding, she decided to investigate and discovered it was fake.

“It sucks because we’re already going through enough in college,” Scriven said. “We don’t need to be dealing with false hope of a job opportunity or actually being scammed out of money.”

Scriven adds that she’s gotten these emails since her freshman year, and now as a junior, she’s come to learn that if something sounds too good to be true, it’s probably a scam.

A few months ago, Marti received a final email from her scammer questioning when she would complete her task. She never responded and quickly deleted the email.

“I’ve definitely learned my lesson. It still concerns me that they have my personal information, but nothing else has happened so I’m not going to worry too much about it,” Marti said. “My boyfriend still makes fun of me for falling for it because all the signs were there that it was a scam, but I didn’t realize it at the time.”

Steffi Marti, a senior at the University of South Carolina, almost fell victim to a fake job scam email that promised substantial wages for limited work hours. The Federal Trade Commission said young people more often fall prey to scams than older people.

Some scammers pose as professors and job recruiters because they know students are likely to trust them and less likely to question the authenticity of the email. Many scams are sent out at the beginning of the school year.

Ruben Conyers Jr., a USC student, began investigating a company that urged him to apply for a summer internship. The proposed job turned out be a scam.

The Federal Trade Commission said citizens lost $328 million in 2017 because of imposter phone, letter and email scams. Ayana Scriven, a USC junior, says she avoids being scammed by researching the names of people who sent her emails.