The Inclement Weather Center that shelters Columbia’s homeless population has been opened seven days this season as Columbia has experienced unusually cold weather for this time of the year.

As wind chill temperatures dropped to the 20s last winter, an old Army blanket that belonged to her father and a backpack of supplies was all Annie Butcher had to keep herself warm. Her usual spot was under a Columbia bridge that sheltered her from most of the wind and rain, but some evenings the temperatures dipped so low she had to seek shelter at the city’s winter facility.

To escape the cold, she spent three nights at the city’s winter shelter out of necessity but she won’t go back this year. Butcher’s worst experience at the winter shelter occurred at the end of December. She recalls an overcrowded bus ride to the facility, lack of cleanliness of the showers and rude interactions with others seeking shelter.

Now, the buses are running again carrying Midland’s homeless from the Comet station on Sumter St. to the Inclement Weather Center. Each year on Nov. 1, Columbia in partnership with the United Way of the Midlands, Transitions Homeless Center and the Salvation Army opens the shelter when temperatures drop below 40 degrees through March 31. As of Nov. 13, the center has been opened seven nights.

The facility located off a gravel road near Riverfront Park has 240 beds divided into men and women sections. The many bunk beds line the walls with personal lockers in between and showers located in the back. Those seeking shelter receive a warm dinner and breakfast with coffee in the morning.

In the past five years, the shelter has not reached capacity even on the coldest winter days, said Craig Currey, president and CEO of Transitions Homeless Center.

“Unfortunately, you can open the Inclement Weather Center but that doesn’t mean that everybody is going to come to it,” Currey said.

Currey said many chronically homeless people choose to stay in the cold for a variety of reasons: Some don’t want to be in the shelter system, they want to stay in their “secret hiding place” or they’re reliant on drugs or alcohol.

One volunteer usually runs security checks to make sure no one brings in alcohol or illegal substances. He recalled a time he asked if someone had alcohol on him and the man pointed to his stomach, implying he had already finished the drink.

Since chronically homeless people are typically not used to living in close quarters, there have been instances at the facility where personal items were stolen and occasional fights have broken out. While altercations have occurred, most people are there to seek shelter from the cold and not cause trouble.

“Generally by the end of the day, people are looking to shower and go to bed,” said Currey.

Butcher, who is originally from New Jersey, is relieved she doesn’t have to use the inclement weather facility. She is no longer living on the streets and is a current resident at Transitions Homeless Center.

“Would I use it again or recommend it? I wouldn’t, seriously,” Butcher said.

There are several health risks associated with staying outside in low temperatures for too long. Those with deteriorating health are more susceptible to hyperthermia and other weather-related issues.

“A lot of the homeless folks have various conditions where their health is not good, their heart is really not good and they shouldn’t be out all night on cold asphalt,” Currey said.

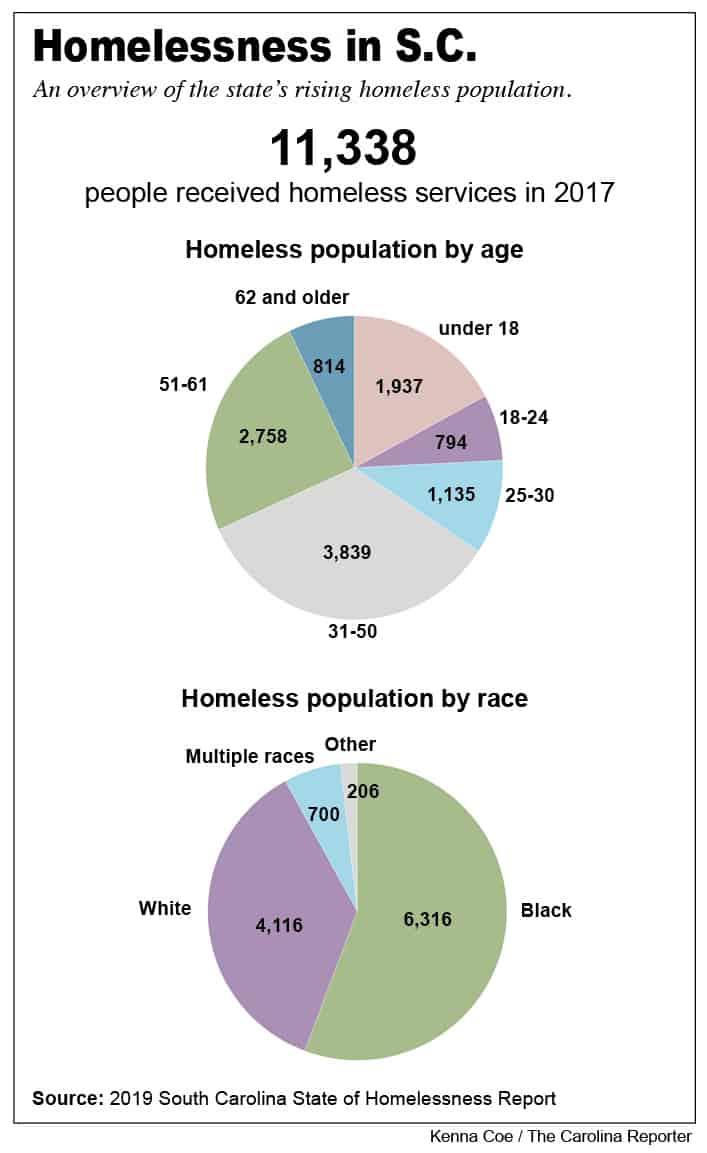

The most recent Point-in-Time Count, administered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, reports Richland County has the largest population of homeless people in South Carolina with 851 homeless and 183 considered unsheltered.

The Point-in-Time Count reflects the number of homeless people counted on a specific night, Jan. 23, 2019. In order to be counted, they have to answer questions ranging from, “How long have you been homeless this time?” to other questions about drug abuse or domestic violence.

The number gives a snapshot of the homeless population and is usually used to compare to homelessness rates in previous years, but it doesn’t fully account for all aspects of homelessness.

One population that often remain invisible from the count are homeless families, said Lila Anna Sauls, president and CEO of Homeless No More, a nonprofit focused on ending family homelessness.

She said many families purposefully hide in fear of being found by the Department of Social Services. This means they’re more likely to be bundled up in a car in a Walmart parking lot opposed to staying on the streets overnight.

While the Inclement Weather Center offers a place for adult men and women to stay, Columbia lacks weather-related emergency resources for families.

“If a family were to show up, a lot of the times they wouldn’t even know where to send them,” Sauls said.

Sauls said children who stay in the cold risk getting sick, meaning more missed school days and the extended likelihood of trips to the emergency room to treat mild illnesses because they typically lack a general practitioner. Sauls said the problem of family homelessness extends into the school and healthcare systems.

“It’s not just one piece of the system that’s broken right now,” Sauls said. “It’s a lot of different pieces that are just not working well together.”

Recently, the city has taken increased measures to remove Columbia’s homeless population from the streets. At the end of September, a few benches that many homeless used to sleep on were removed from Lady and Lincoln Streets near the Vista.

Finlay Park is an area that many homeless people gather and sleep. A recent $18 million restoration plan was announced to renovate and beautify the park. While the plan has not been approved yet, it poses the question whether the homeless will have to leave the park.

Butcher said when she lived on the streets, police officers would come at 6 a.m. to areas where homeless people were gathered and shine their flashlights in their faces and tell them to leave.

“I guess it’s part of the law to clean up the town or whatever it is,” Butcher said. “Personally, I didn’t see us doing any wrong.”

Volunteers prepare the facility by moving chairs and organizing the dining area before those seeking shelter arrive.

Soap and toiletries are collected by local non-profit organizations for the homeless to use at the shelter.

Busses begin arriving at the shelter located on Calhoun St. around 6 p.m. and the homeless people file into the building to go through security checks before entering the dining area.