Children play rock, paper, scissors in the lobby of the Statehouse while their parents celebrate the signing of a bill that requires mandatory screening for dyslexia in early kindergarten and elementary classes.

Feeling overwhelmed, lonely and unable to find appropriate help for her child at his school, Jennie Garris found a connection with Decoding Dyslexia, an organization that has pushed for mandatory school screening for the learning disability.

Garris, the mother of four boys, was at the State House Thursday with other members of the national organization to celebrate passage of legislation that requires an annual screening between kindergarten and second grade. Gov. Henry McMaster signed the bill in May.

Garris said before her son’s diagnosis one teacher thought her boy was an attention seeker who disrupted class.

“This is something that has to change as South Carolina is a state that we’re not doing a good job recognizing screening what dyslexia is and teaching our teachers what dyslexia is,” Garris said. Dyslexia is a disorder that makes it difficult to read or interpret words, letters, and other symbols, but that does not affect general intelligence.

The community relationship Garris established with Decoding Dyslexia became even greater after finding out at age 40 she was also dyslexic. Finally, the pieces to her once complicated puzzle fit.

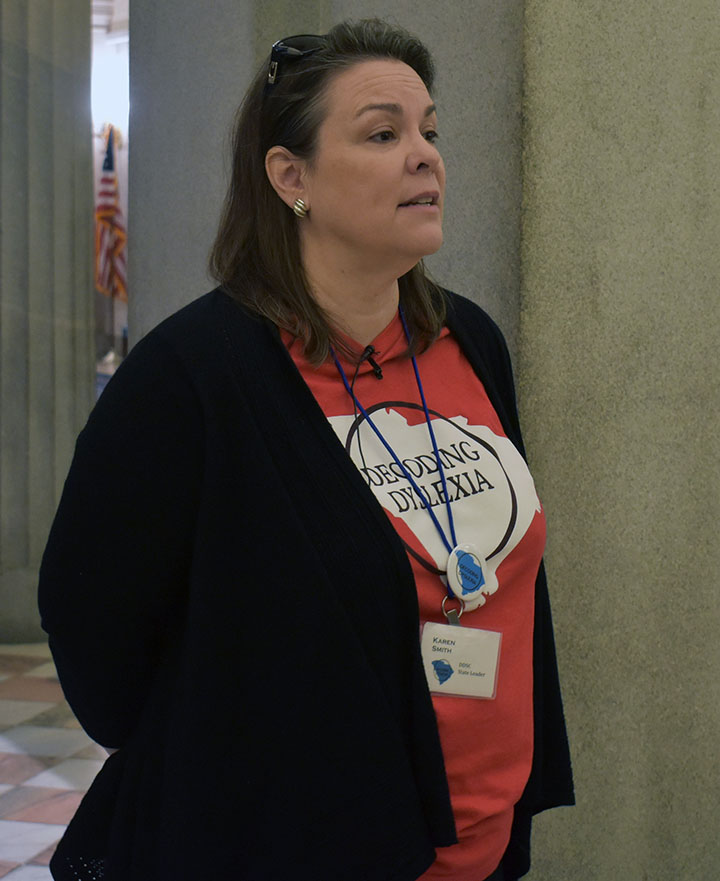

As they waited for McMaster to join the celebration, Karen Smith, one of Decoding Dyslexia’s state leaders, talked about a similar journey to diagnose her three sons. Smith connected with other parents on Facebook.

“I felt alone dealing with my problem and alone with the ideas of how to solve dyslexia because it wasn’t being recognized yet in the school,” said Smith.

The legislation calls for dyslexia screenings for dyslexia for students in kindergarten through 2nd grade who are experiencing academic and/or social-emotional difficulties.

With the passage of the bill, “I knew there wouldn’t be children falling through the cracks, unidentified with dyslexia and just being looked at as lazy or slow,” said Smith. But most importantly she wants to hold our schools accountable to the law of screening children for dyslexia.

After working in schools in South Carolina and other states, Jessica Albrecht said she realized dyslexia is an issue that the entire country is behind on.

“I believe this is a very good step, but on some level, this is only a baby step,” said Albrecht, the mother of a dyslexic daughter.

While tutoring her friends’ children, she at first didn’t understand why she couldn’t help in the way she wanted. At a friend’s urging, she began to read more deeply about the learning disability that makes decoding language a problem.

Parents often expect schools to recognize signs that their child is struggling, but too often receive a mis-diagnosis, she said.

“Dyslexia is more common than they think and it’s not what they think. It’s more than just confusing your b’s and d’s,” said Albrecht.

Members of the parent grassroots organization profit Decoding Dyslexia wear red shirts to celebrate passage of legislation that would require mandatory screening in schools for the learning disability.

Karen Smith, one of many state leaders of Decoding Dyslexia in South Carolina, was first inspired to join the national movement because her children have dyslexia.

Jessica Albrecht, a former tutor who helped students with dyslexia, says too often schools fail to understand the learning disability.

Jennie Garris, the mother of two dyslexic children, hopes legislation requiring mandatory school screening for the learning disability, is the first step to many more changes.