It’s a beautiful day outside, but behind closed doors, deepfakes are a growing concern at The Post and Courier’s Columbia bureau office on 2101 Gervais Street. Lee Wardlaw

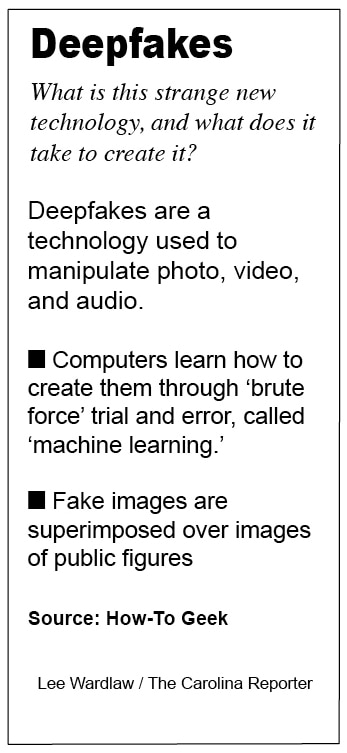

Millions of Americans view their news through social media websites,and Some of the posts that they share are affected by deep fakes, a newly emerging artificial intelligence technology that can create fake photographs, audio, and videos.

Andy Shain, chief of The Post and Courier’s Columbia bureau, said that deepfakes are deceptive to the public and that national media has expressed a growing concern with the technology. Politicians, celebrities and other prominent figures in the news have often been the subject of deepfakes, the human synthesis imaging so deceptive as to fool experts upon first glance.

“Being a journalist who covers the state, who covers politics, we’re always susceptible to and always on alert for any sorts of things,” he said.

With the presidential election upcoming in 2020, the public should consider the dangers of deepfakes, he said. South Carolina residents should especially be on high alert, as S.C. is scheduled to be the third state to vote in the Democratic presidential primary Feb. 29.

Andrea Hickerson, the director of the University of South Carolina’s School of Journalism and Mass Communications, is also worried about the growing problem of deepfakes. Hickerson said that deepfakes could be particularly dangerous if deployed in politics.

“What are our methods of verification? It’s really hard to detect, and we can’t trust our eyes,” Hickerson said.

Hickerson is a member of The Ethics and Governance in AI Initiative, a joint program between the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University.

The goal of the project, led by Matt Wright of Rochester Institute of Technology, is to develop an artificial intelligence tool for journalists to detect deepfakes.

“We want the tool to be free and accessible to all journalists,” she said.

Deepfakes often gain popularity on social media, where users can share content with just one click. When doing this, many forget to check the authenticity of the news source. Former President Barack Obama, Russian President Vladimir Putin and other internationally recognized figures have been targeted in recent years.

“Part of deepfakes is sometimes you don’t realize what you’re doing,” Shain said.

Shain offered one simple step for people to detect deepfakes.

“Vet anything that you see that you’re wondering about, try to see what the truth is,” he said.

Researching sources is one of the best methods to debunk deepfakes, and it can be done by searching fact-checking websites such as PolitiFact and Snopes. While deepfakes can deceive voters, they could be especially dangerous for journalists and the media companies that they work for.

As part of the Ethics and Governance AI Initiative, Hickerson interviews journalists.

“This is the first project I’ve worked on that journalists wanted to remain confidential or anonymous. Journalists are worried about being targeted,” she said.

Shain said that The Post and Courier has a strict policy for sources to maintain credibility and avoid potential legal action.

“We’re a business and like anything else, we have to protect ourselves from things,” he said.

First hand sources are preferred, and caution is placed on second-hand, third-hand, and anonymous sources. At The Post and Courier, full confidence is needed before information from a source is published. Shains said that the individual would need to back up the claim publicly, and he would need to have enough certainty to testify the source’s authenticity in court.

“When in doubt, leave it out,” Shain said.

Hickerson said that the first prototype of the technology would be released in November. It would allow journalists to detect the likelihood that video and audio was edited by cutting and pasting a link into the program.

The artificial intelligence would be unique because the process of syncing both video and audio is not supposed to be easy.

If available on the market, Shain said that he would be open into investing in a detection product. “It would be great, I mean, to have a tool that would help us maybe identify a mask, something that’s trying to hoodwink the public,” he said.

Andy Shain, the chief of The Post and Courier newspaper Columbia bureau, said that he hasn’t experienced any deepfakes, but expressed concern that it could be an issue in the 2020 presidential election. Lee Wardlaw

At The Post and Courier’s Columbia bureau, journalists strongly voice their first amendment protections. Lee Wardlaw

Shain said that deepfakes are low tech in the newspaper industry, but can be easily created. Fake e-mails and text messages are common. Lee Wardlaw