Dillon Four District Office, was built in 2008 after government funding was granted to construct this building and Dillon Middle School (formerly J.V. Martin Jr. High School).

Though his background was not in education, Senator Greg Hembree is passionate about creating a well educated community to ensure a brighter, safer future for South Carolina’s next generations.

Superintendent Ray Rogers of Dillon School District 4 has been a catalyst in making change for the school district in his 27 years as superintendent.

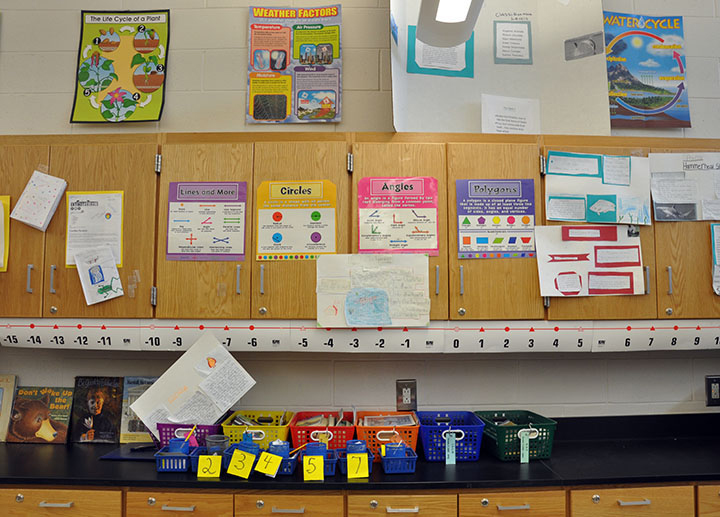

Courses like Mrs. Anne Johnson’s gifted and talented course offer students of Dillon Middle School the chance to take on challenging projects and work on building research skills.

Teachers agree that hands-on projects are an exciting way to keep students engaged and interested in learning, however the fight for funding makes it difficult to have the necessary resources to make these projects possible.

It is a chilly fall morning when the superintendent of Dillon County School District Four receives a call from a parent, notifying him that her five children would not be making it to school because she has no means of transporting them.

Superintendent Ray Rogers jumps into his small van and heads over to the home to find a car in working condition. After asking the mother why she could not take her children to school, she explains to Rogers that if she were to have taken her children to school, she would not have enough gas to make it to work.

This scenario is one of countless ones that Rogers has faced in his 27 years at Dillon Four. It is not uncommon for students to often be neglected by their parents and guardians, leaving them to find their own way home after school, practices and other extracurricular events. That’s when school resource officers, teachers and other faculty step in to help their students.

In a state that ranks 41st in education as of Feb. 2018 by USA Today, it is difficult to find a one-time solution to the rampant problem in an education system that has lagged since South Carolina moved from an agricultural economy to an industrialized one. South Carolina has struggled in the national rankings for years, usually sitting close to the bottom. But where does the problem lie? Does the issue solely root itself in funding? Do legislators and school districts agree on the causes and effects for the case?

“The prevailing theme in South Carolina is that we underfunded K-12 pretty badly,” said State Sen. Greg Hembree, R-Dillon, a Horry County native. “But that’s not the case.”

When looking at funding for South Carolina, Hembree compared state funding to California and Illinois schools, which are union states that pay teachers more than South Carolina pays teachers but have the same average per-pupil spending.

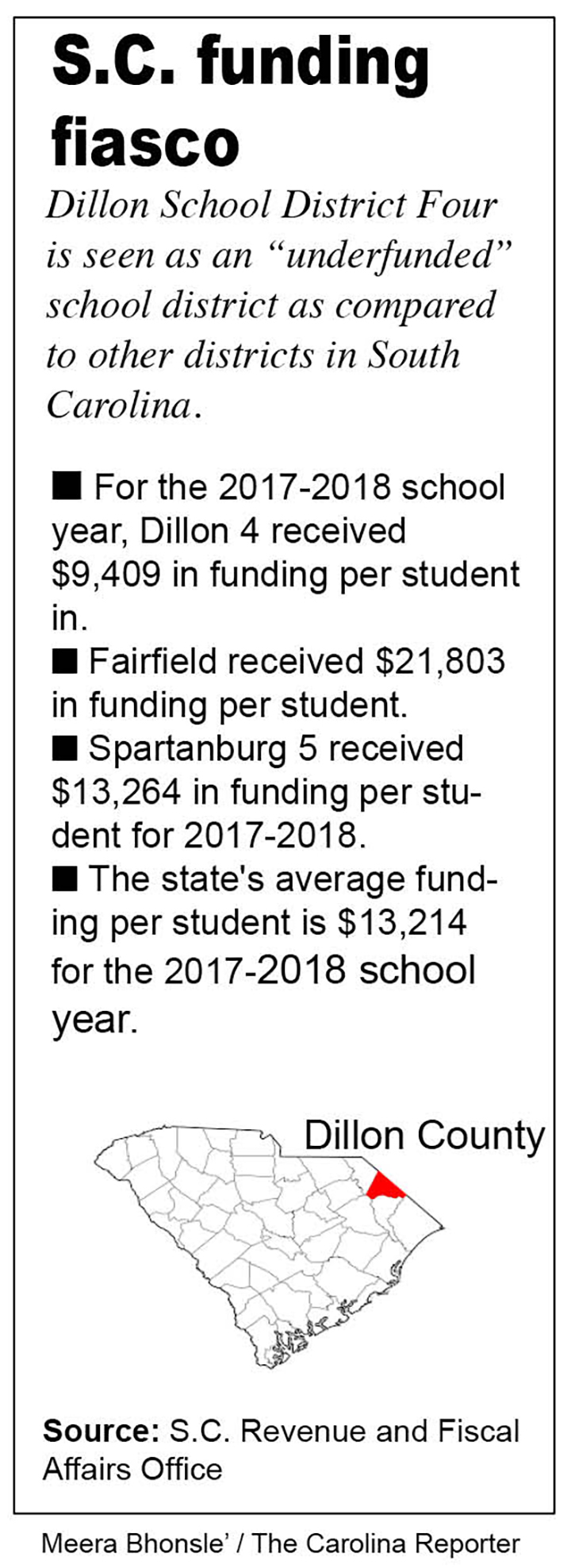

Dillon County School District Four — at 90 percent poverty — is among two dozen districts that receive less funding than large urban districts in S.C. because the formula is based on property taxes.

“There are major problems, especially with rural South Carolina,” Rogers said.

A lawsuit pushing for more equitable funding for the state’s poorest districts took more than 20 years to reach the state Supreme Court. In 2015, the high court ruled that it was up to the state legislature to come up with a more equitable formula; that ruling was overturned two years later.

Dillon County was included in the “Corridor of Shame,” an investigative documentary by Columbia public relations executive Charles T. “Bud” Ferillo. Released in 2005, the film exposed conditions of schools along the I-95 corridor, which in turn brought light to the matter of poor funding for lower-income districts.

Across the board, statewide school funding has increased in South Carolina from the 2013-2014 school year to the 2017-2018 school year. However, cases where that may not be enough are what Rogers calls “blessings.” In 2007, then-Sen. Barack Obama made a visit to J.V. Martin Junior High School during his presidential campaign after seeing Ferillo’s documentary. Rogers shuffled through his folder filled with photographs of Obama, proudly showing them, noting that “no matter what you think politically, he is a very brilliant man.”

Obama’s visit resulted in funding for the rebuilding of J.V. Martin now Dillon Middle — and the Dillon Four district office facility. The facilities were completed in 2012, but there was still a hole in the heart of Dillon Four — a brand-new school, yet the students were still severely struggling.

Six years later, the beaming, fresh Dillon Middle School stands tall, full of sixth, seventh, and eighth grade students, many of whom do not know the history of their school. Assistant principal Walter Jackson did not wish to speak on funding issues because he felt that was something the principal or superintendent could address better, but he did discuss the atmosphere and enhanced learning in the new building.

“We have a clear focus for the future and are getting our students ready for a promising future in the best way we can,” Jackson said.

He also showed his appreciation for the new technology that came along with the building of the school.

“The technology is the way of the future, and the fact that it is used instructionally every day in the classroom is amazing,” Jackson said.

Teachers who have been with Dillon Middle School since before the construction of the new building feel thankful for the new school. Anne Johnson, teacher for gifted and talented students spoke enthusiastically about the technological enhancements of the new building.

“Technology enhances learning,” Johnson said.

She and curriculum specialist Kathi Campbell agreed that receiving new and improved technology in the classrooms gives students the opportunity to experience the world around them, especially since many of them have not had the opportunity to go far from their communities.

“They only know the street they live on,” Campbell said, stressing the importance of virtual learning simulators and other new programs that were made possible through federal funding granted to the school.

Though the virtual experiences have played a significant role in students’ learning, a large funding goal is to allow students to take field trips.

“We’re a poverty-stricken district,” Johnson said. “Our kids don’t have twenty dollars to hand out to go here and there.”

This is where virtual learning is useful in districts like Dillon Four where field trips are not always an option.

Hembree and Rogers both noted students near the coastal region of South Carolina often have never even seen the ocean — though many of them live only a few miles from it. Hembree introduced an idea discussed by the education committee of a traveling display of modern-day industry jobs and wildlife simulators to move from school to school in rural areas. This would allow students to have some kind of experience with the world outside of their communities where poverty is high, income is low, and many families struggle day to day.

Hembree finds that having funding for learning materials and technology is important, but in certain scenarios, continuously funding schools “is like pouring water on concrete.” He believes that involving parents and community members in the lives of students is the best way to ensure educational success.

Rogers, Jackson and both Dillon Middle teachers all agreed that a change in community environment is what the state needs to ensure a promising future for South Carolina K-12 students.

“It’s nothing more than a marketing campaign — I think that would be money well spent,” Hembree said in regard to how the community can be more involved in encouraging education.

Hembree explained that the best way to reach out to parents who may not have gotten a quality education is to teach them the importance of encouraging their children to love learning. He referred to the “if you can read this, thank a teacher” bumper stickers from the late ’90s and how this is an effective tool to remind community members that “teaching is an important and noble profession.”

Rogers agreed with Hembree, although he made the point that some communities, like Dillon, are filled with children raised by single parents, many of whom did not receive a high school diploma and work two to three jobs to support themselves and their children.

“With the parents that have more than one job, it’s difficult for them to make it to their child’s events,” Rogers said.

Rogers noted that there is no industry in Dillon — no large plants or factories — making it difficult for the economy to open up and generate a steadier income for the residents of the county.

After nearly 20 years of being kept on hold and a visit from a senator who would eventually become president, Dillon Four received the new school it longed for. But funding for education is not a “cut-and-dried” topic that can easily be resolved when faced with issues, especially in South Carolina where economic growth and industrialization is unforeseeable in many rural areas.

While the new building was a major improvement from its former facility, the community of Dillon has not seen the substantial development in its community economy that would trigger growth, which is the indefinite challenge the community will face.