Allen-Benedict Court, public housing built in 1937-40, has 18-inch closets and no washer or dryer hookups. Residents pay 30 percent of their monthly incomes in rent.

State Sen. Marlon Kimpson’s district includes North Charleston, which has the highest eviction rate in the U.S.

Grove at St. Andrews is one complex within the Dutch Fork Magistrate area. The complex has 700 units and has filed for eviction 218 times and gotten 20 writs of ejectment since Jan. 1.

Part 2 of a two-part series

A combination of rapidly increasing rents, low wages and little political support has created a situation where evictions become inescapable for thousands of South Carolina families.

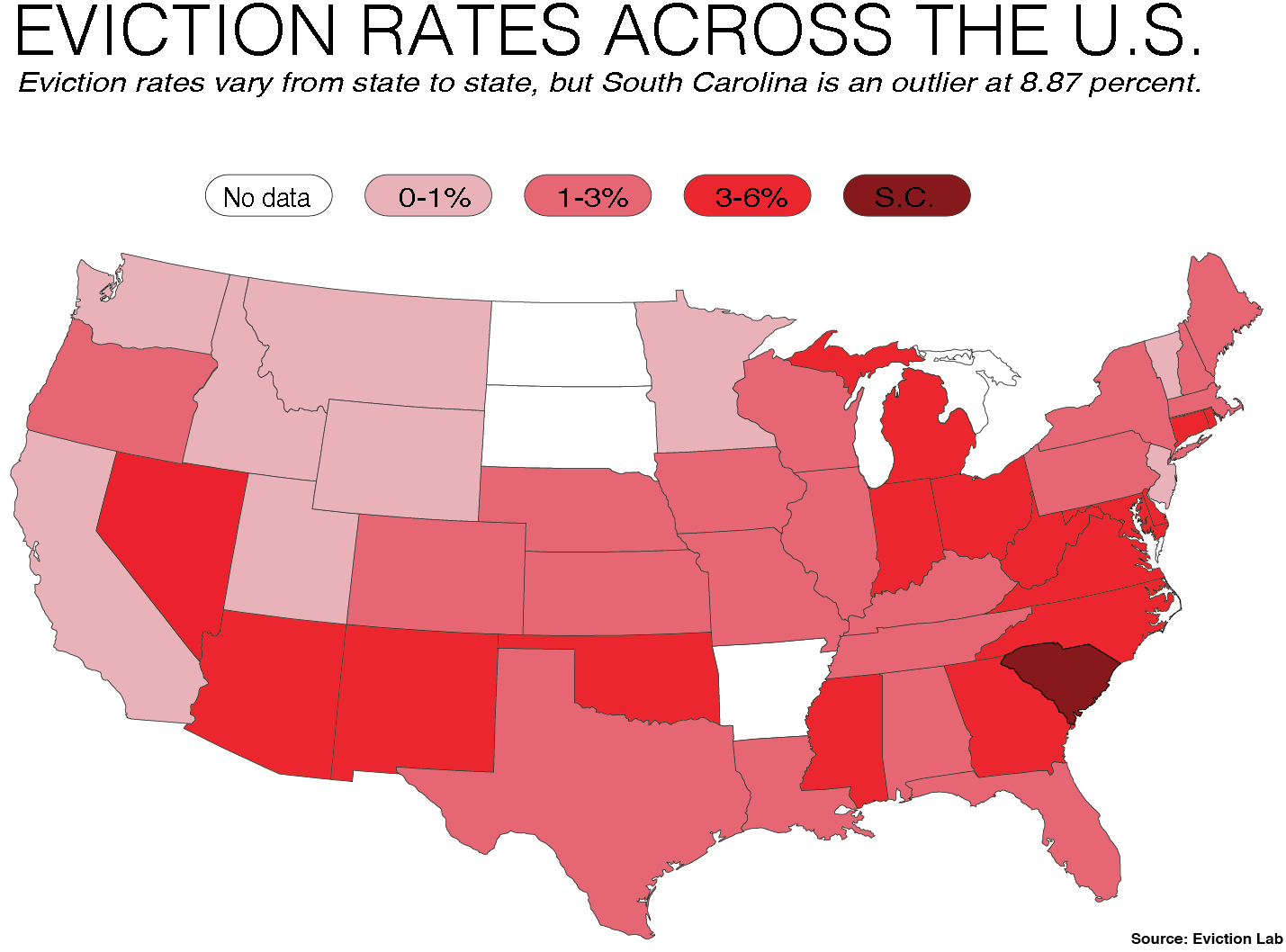

People renting in Columbia, South Carolina, are evicted at the 8th highest rate in the country, according to recently released data collected by Princeton University researchers and nonprofits.

The state leads the country in evictions per household. While the data isn’t comprehensive — three states have no data at all, and selected counties are missing — the study shows an epidemic of evictions across South Carolina.

And the problem in Columbia is only getting worse. About 8 percent of households were evicted in 2016, up from 3-4 percent in every year 2010-2015.

“The environment in which we live is hostile to the working-class citizens of our state and even more hostile to people who are of less means,” said state Sen. Marlon Kimpson, D-Charleston. “We’re taking, taking, taking more away. And somehow, we expect for this society to coexist. When people work 40 hours a week and still don’t earn a livable wage, still are not able to get health care, still are not able to provide a place to live, we’ve got a problem.”

Kimpson recently was awarded Clementa Pinckney Elected Official of the Year for his work toward affordable housing in the State House. The award is named for the late state Sen. Clementa Pinckney, who was killed in the 2015 shooting at the church he pastored, Emmanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston.

North Charleston, No. 1 in the country for evictions per household, is in his district. He’s sponsored bills that would allow local governments more leeway to encourage affordable housing, create tax credits for developers to build low-income housing, and increase funding to affordable housing trust funds. None became anywhere close to law.

“It’s not the will of this body to pass it,” Kimpson said. Even the eviction information hasn’t spurred interest. “There hasn’t been one conversation on the Senate floor about the data,” he said.

Todd Shaw, chairman of University of South Carolina’s political science department, sees a connection between evictions now and homeless in the 1980s. Both have always been around, but quantifying the problem can provide an impetus for discussion.

“There was a whole discussion, particularly at the end of the Carter and into the Reagan administration, about homelessness as a growing problem,” Shaw said. “This crisis of affordable housing has actually been going on for decades now.”

Particularly in Columbia, affordable housing has become increasingly difficult to find. The Richland County rental occupancy rate has fallen to 6 percent, and a recent student housing boom offering expensive amenities has allowed other landlords to jack up rents.

“That’s where government has to step in. Government has to say, ‘We recognize you’re not going to be able to meet that demand,’” Shaw said. “Unfortunately, government has been moving in the other direction.”

Just last week, U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Ben Carson announced rent hikes and potential work requirements for public housing.

“In addition to turning a blind eye to wages in this country, there’s been a systematic attempt to defund the programs that help people pay for public housing,” Kimpson said.

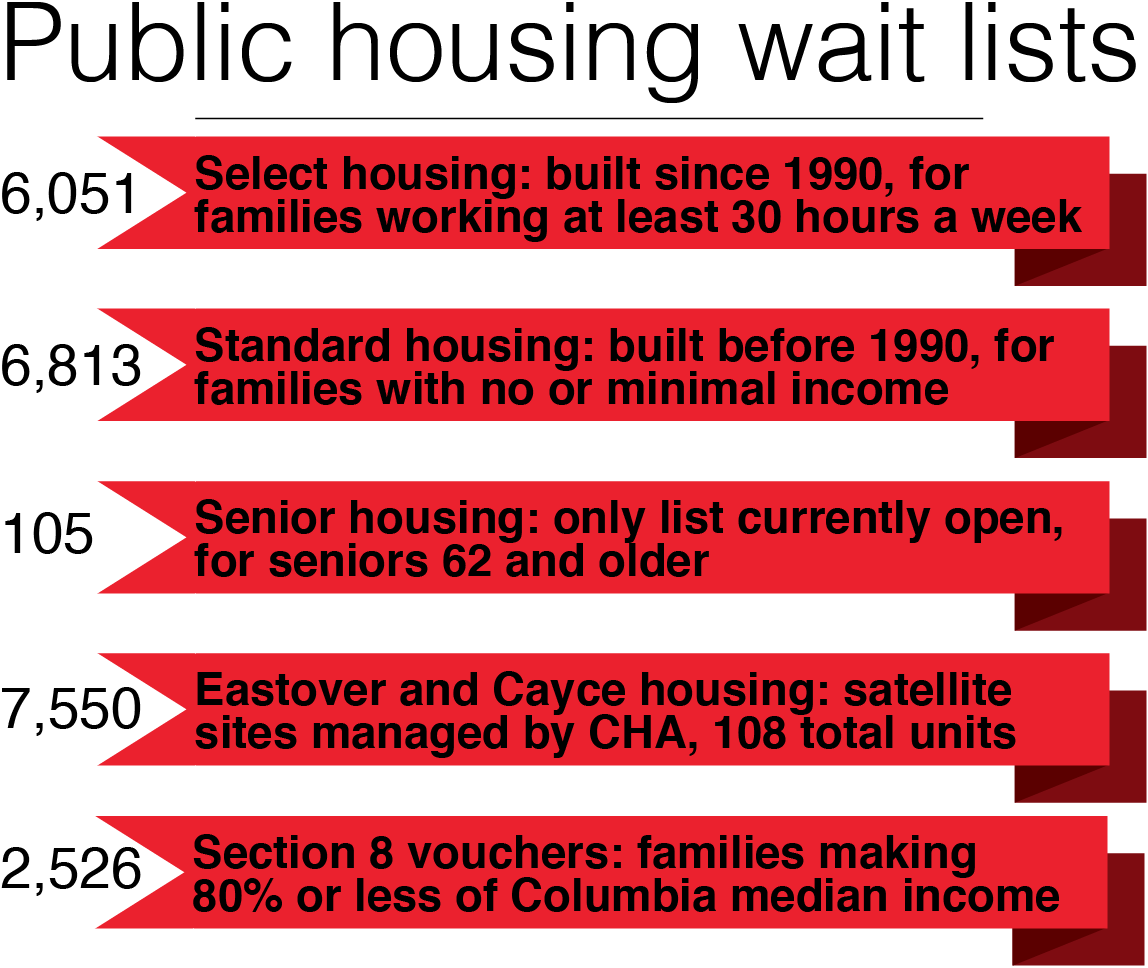

In August of 2016, the Columbia Housing Authority opened applications for its housing voucher program for the first time in three years. The vouchers subsidize rent for families earning below 50 percent of the area’s median income. In just over 48 hours, more than 32,000 families submitted applications.

“When we advertised it, I think we knew we were going to get a lot of applications,” Nancy Stoudenmire, the director of human resources and planning, said. “I don’t think any of us knew quite how many applications.”

Stoudenmire has worked for the housing authority since 1977, about the time voucher use was starting to replace large construction projects in affordable housing policy. Since then, national programs have favored tearing down dense projects and replacing them with mixed-income communities. The problem, she said, is that the total number of units decreases.

While vouchers allow families to find their own housing, it also obligates them to find housing cheaper than the regional fair market rent, decided by the federal Housing and Urban Development department. Columbia is in a region with three rural counties, which drives down the estimate. In 2018, the fair market rent for a two-bedroom unit is $891, including utilities. That’s virtually impossible to find downtown, where students are willing to pay from $600 to $1,000 per bed.

The student housing developments, which added about 5,000 units in the last four years, were encouraged by local tax abatements provided by the city. Other abatement programs have encouraged renovations of old and historic buildings. To date, no such abatements have been offered for affordable housing developers.

“City Council and (Richland) County Council could create incentives for developers to build affordable housing and they’re not,” Stoudenmire said. “We even had one council member say he didn’t want to build housing for poor people. I sat there in that meeting and I was shell-shocked. I couldn’t believe anyone was that short-sighted.”

The city voted in February a renewed effort for affordable housing, but guidelines for new incentives aren’t likely to come out until October, according to Gloria Saeed of the Columbia Housing Development Corp. A quarter million dollars per year will be added to the quarter million already available in loans for developers building affordable housing.

Lila Anna Sauls, the president and CEO of Homeless No More, thinks nonprofits could be part of the solution to the affordable housing crisis. Columbia-based Homeless No More, which already provides some long-term rentals for previously homeless families, is starting construction on a 16-unit affordable housing development. The project is expected to cost $2.6 million.

“I think nonprofits are going to have to start stepping up more and figuring out creative ways to do affordable housing,” Sauls said. “The only issue is we’re not going to be able to do hundreds of units at a time.”

Like Stoudenmire and the Housing Authority, Homeless No More doesn’t consider evictions the same way traditional housing managers might when accepting families for housing. Almost everyone the nonprofit helps have faced evictions in some form, Sauls said. With the 11 units currently managed by Homeless no more, tenants pay between $450 and $575 for three or four bedroom units. Not a single tenant has been evicted, although one came close.

Even with costs that low, though, single income families can struggle to pay rent. For someone working full time and making minimum wage, a rent of about $375 is considered affordable, according to federal guidelines that say only 30 percent of income should go toward rent.

“The bottom line is, our families need to make more money,” Sauls said. “I think housing is the hub of the wheel.”

Without housing or a mailing address, families lose out on other benefits like food stamps and other types of federal aid. It also makes it more difficult to find a job.

“I’d go so far as to say that if you solved the housing crisis in America, you’d solve the poverty problem in America,” Shaw said. “That’s how important having a home and having a place to live that is safe and affordable is to people.”