Dr. Mamphela Ramphele speaking at University of South Carolina’s School of Law event, Women as Agents of Change in Rule of Law, on Thursday, February 22, 2018.

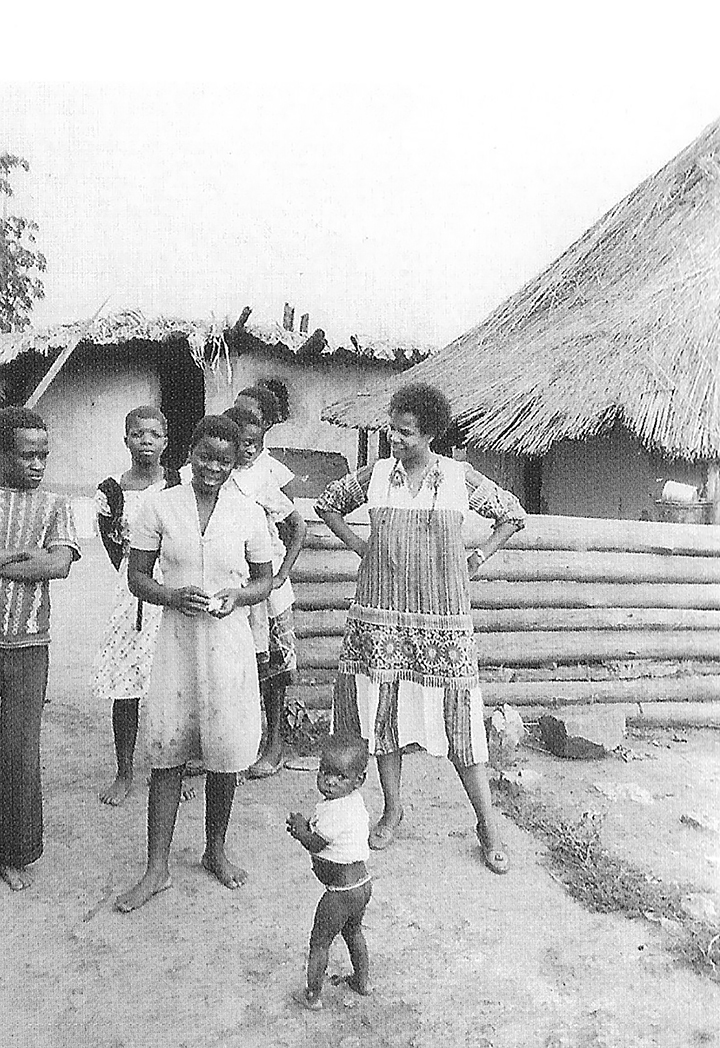

Dr. Mamphela Ramphele at Zanempilo Community Health Centre in Zinyoka village outside King Williamstown. Photo courtesy of Dr. Mamphela Ramphele.

Dr. Mamphela Ramphele with colleagues as an intern at King Edward VIII Hospital in Durban. Photo courtesy of Dr. Mamphela Ramphele.

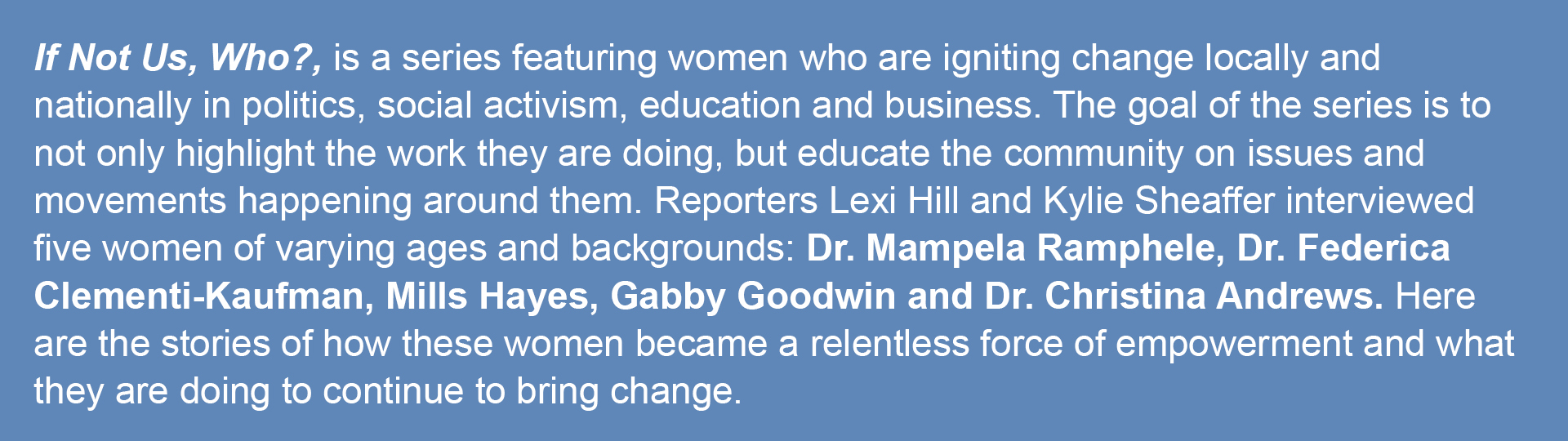

Ramphele with some of Tickeyline villagers, who she worked with while at Ithuseng, the health project she started in Lenyene. Photo courtesy of Dr. Mamphela Ramphele.

Segregated past

Dressed in a vibrant, fitted kaftan and head scarf, symbolic of the deep heritage sewn into the fabric of her home country, Mamphela Ramphele begins to explain the history of South African politics.

“The old system was a colonial apartheid model that excluded the majority of the population,” said Ramphele, a social anthropologist, medical doctor and activist from South Africa.

This system began in 1948 after the Afrikaner National Party, an all-white government, came into power. Under apartheid, non-white South Africans had to live in secluded areas separate from white people and use segregated public spaces.

This continued into 1958 when the new prime minister, Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd, segregated the community further in the hopes of mitigating any revolt of the majority, non-white South African population.

This new effort, the Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act of 1955, led to 10 separate Bantu homelands. The Bantustans, as they become known, was their new citizenship, effectively removing all non-white people from the national government and limiting their political rights.

This racial segregation is rooted in the history of South Africa, dating back well before apartheid. In fact, this effort to weaken the majority population actually began around 1913, just three years after South Africa got its independence, when the 1913 Land Act was passed, forcing black Africans to live in reserves and banning them from working as sharecroppers.

This deep-seated history is why it took more than 50 years, and countless activists led by the African National Congress, to end this segregation and push for a more equal South Africa. It wasn’t until 1994 that a new constitution was ratified and the first majority non-white coalition government, led by Nelson Mandela, won the election.

“The new system is a constitutional democracy where everyone is equal before the law, where there is explicit anti-discrimination on any ground and where there is a promotion of unity and diversity,” said Ramphele. The time between the old and new South Africa is where Ramphele’s story starts.

Rooted in activism

“I was too young to understand it, but could see that something was wrong,” said Ramphele. At the age of six, she was living in a mission village with her family that was dominated by the Dutch Reformed Church, led by a leader and pastor called a Dominee.

It was here that Ramphele saw firsthand how the apartheid ripped apart communities like her own. The Dutch Reformed Church justified the apartheid as a God-given way of life.

The idea was that because God created everyone, no one should “put things together that God put apart,” explained Ramphele.

Village leaders governed following these beliefs, teaching members of the village that “you are inferior because you are black and we are superior because we are white,” said Ramphele.

People were required to be baptised, confirmed and active-churchgoers. “If you don’t do these things, then you aren’t allowed in the village,” said Ramphele.

As a result, when one of the villager’s mother died, she was not allowed to be buried in the church because she didn’t fall into line with the Dominee’s sententious ideals. “Recalling the story, Ramphele’s brows furrowed, “Everyone just kept saying it was unjust!” The beginning of a revolt had occurred.

There was a heightened urge for resiliency in urban areas around 1955. “They were mobilizing people. They would have bus strikes and other strikes against the system,” said Ramphele on the atmosphere around the time. Subsequently, her village followed suit, and stood up for the woman and her mother.

Protesters rang the church bell, which could only be rung by the church ringer who is under the Dominee’s instructions. “There was chaos,” said Ramphele. “My father took us, and my mother who was expecting a little baby, to his rural home about 60 km away from where the village was.”

When they came back about a year later, the village had been completely decimated. “There was a division between those who supported the Dominee and those who opposed him,” said Ramphele. Those who opposed had been forcibly removed by the police. “Suddenly, the village was declared a black spot in a white area and people were then forced to leave the area,” said Ramphele.

Living the fight

When Ramphele was beginning her education to become a doctor, that same Dominee from her village proved to be a catalyst for her future.

“After hearing that I wanted to become a doctor, the Dominee told me my father was dying,” said Ramphele. “And he said, you can’t become a doctor, your father is dying. Who is going to pay for you,” said Ramphele.

His rebuffs didn’t stop her, though. “That made me more determined. I said I’m really going to show this man, that whatever he thinks, I’m going to be a doctor. I’m determined to be a doctor.”

So, in the late 1960’s, Ramphele began taking pre-med classes at the University of the North, and eventually began her medical career at the University of Natal Medical School in 1968. At that time, that was the only university that allowed black students to enroll without prior permission from the government.

While in college, Ramphele was one of the founders of the Black Conscientious Movement, “which was really an approach to mobilizing people to acceptance,” said Ramphele. “They are non-status, non-European, non-white, so the idea was for them to define themselves in more positive terms and be agents of their own liberation.”

Throughout her time as a student, Ramphele became involved in more political activism. She worked with the South African Students’ Organisation, a student organization that resisted the apartheid through political action. Before graduating in 1972, when Ramphele qualified for her degree and became a doctor, she became the chairperson of the local SASO branch.

The next steps

After completing her internships in the Eastern Cape and the Limpopo province, Ramphele founded the Zanempilo Community Health Care Centre, one the first public healthcare programs apart from the public sector in South Africa.

“In South Africa during the apartheid system, if they didn’t like you, or found you to be a threat in the sense of possibly mobilizing people to rise against the regime, they declared you a terrorist or a communist and you would then be restricted either to house arrest or a small area where you can work. So, for eight years, I was restricted,” said Ramphele.

During these years, Ramphele worked with poor communities, mainly women and children, and men who had worked within the migrant labor system.

“The work we did there completely transformed people’s lives,” said Ramphele. “People would assume that you have six children and three of them would die, but children don’t have to die from preventable illnesses.”

Ramphele and her team tackled infant mortality and good nutrition. In order to do this, they prevented the death of infants because of lack of fluid or hydration and encouraged people to have their own gardens so they could have fresh fruit and vegetables.

“It was a revolutionary community health problem that focused on promotion of well being, prevention of ill-health and curative treatment when people were ill,” said Ramphele.

After those eight years, Ramphele went back to the university environment and started working at the University of Cape Town as a researcher. It was there that she curated the knowledge and studies that contributed to her book, A Bed Called Home, which she published after studying the migrant labor system in South Africa.

A bed called home

“The sum total of the home of that man, who is an able man, whose wife was living in rural areas, was a bed. That’s it,” said Ramphele while describing the environment where migrant laborers lived.

“Upon arriving, you can expect to see row upon row of beds, which are not beds as you and I would expect, but slabs of concrete with numbers on them,” said Ramphele.

The migrant labor system, which was created under Arch British Colonial Imperialist, Cecil John Rose, began after gold and diamonds were discovered in South Africa.

“He decided as the prime minister of the colony, that we must keep African people under a very tight leash,” said Ramphele. “One of the ways to do that was to bring African men to urban areas to work, where they were kept in a highly policed environment so they can’t steal the gold and diamonds they’re mining.”

So, in order to answer the question, “What happens when you restrict people’s physical space,” Ramphele focused on these living conditions, later attaining her doctorate in anthropology as a result of her research on the politics of space.

”If you restrict people’s physical space, their psychological space in also restricted,” said Ramphele. “They cannot develop spiritually and you’re basically undermining their humanity.”

Tapping into her experience as a medical doctor and research as an anthropologist, Dr, Ramphele took on the next phases of her life. She became the deputy vice chancellor at the University of Cape Town, where she was able to help transform the university into a system that “welcomes men and women, black and white.”

As a result of her work, Ramphele became the president of the University of Cape Town from 1996 to 2000. From there, she went on to work in Washington, D.C. as the managing director of the World Bank where she dealt with issues of human development. In 2004, Ramphele was asked by both World Bank and the United Nation to co-chair a global commission on migration.

“Nothing stuck, nothing worked,” said Ramphele. “So, I went back to South Africa and worked in the Eastern Cape to try what I had been working on at a national level at a community level. Fantastic possibilities, but again; the corruption in the country meant that they could allocate money for the project, but it never arrived.”

Despite years of effort, with obstacles circling at every turn, Ramphele has continued to help the people of South Africa achieve everything they’re capable of achieving.

Ramphele Now

“I’ve been an activist now for 50 years. I still don’t give up. And the reason is simple,” said Ramphele. “If I give up, what do I do? I am not prepared to sit down and fold my hands and be depressed. I believe South Africa has all the opportunities and resources to become a great country.”

Looking down at the pattern on her dress, Ramphele laughs and says, “One of the tragedies of Africa is our continent is a cradle of humanity. We should be the leaders. We are people who invented writing, mathematics, cosmology; but that is all lost in the wash. Instead, we tend to emulate other cultures rather than showcase what the continent has to offer. So, this is it!”