A snapshot of Clementi’s office, which is lined with movie posters and other artwork from her studies. Credit: Lexi Hill

Federica Clementi posing in her office. Credit: Lexi Hill

Clementi talking about her book. Credit: Lexi Hill.

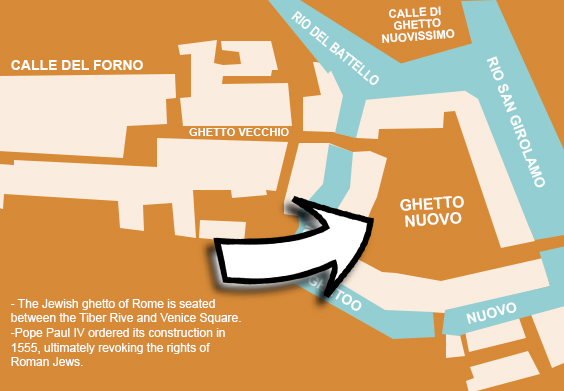

A map of the Jewish Ghetto, the area where Clementi grew up in Rome, Italy. Graphic: Lexi Hill.

The reminder

Federica Clementi adjusted her scarf and laughed. “Do you really have to take pictures of me?” the USC Jewish Studies professor asked. “I’ve always been absolutely terrible in photos.”

She has studied photographs, and the people in them her entire life, in an effort to unravel the stories of those who suffered and survived the Holocaust, and the generations who have come after.

Reminders of Clementi’s Jewish identity are visible in her office, which is a reflection of the woman who has spent a lifetime devoted to understanding mass genocides and how people can evolve and become more understanding.

Her office walls are home to Russian movie posters and antique furniture fill the room. Her book, Holocaust Mothers and Daughters: Family, History and Trauma, sits front and center on her desk.

“I never spend any time here,” said Clementi, whose work consumes her. Clementi’s interest in Holocaust survivors began in her early childhood and has continued throughout her academic career.

In fact, Clementi has committed her life towards studying the Holocaust from the perspective of its victims. Subsequently, she’s become an expert on the long-term psychological effects of genocide survivors.

“The children of Holocaust survivors tend to carry a lot of the PTSD symptoms of their parents, particularly in Israel,” said Clementi.

The Holocaust, the mass extermination of European Jews by the German Nazi regime, occurred throughout Europe from the early 1930s to 1945. The discrimination towards the “other” occurred for years before the Holocaust though, and still exists today.

It’s nearly impossible to calculate the number of victims of the Holocaust, although 6 million Jews are believed to have perished in the concentration camps. The United States Holocaust Museum conducted a study that estimated that over 15 million people were murdered during the genocide, including Nazi political opponents, the handicapped, homosexuals, gypsies and others deemed imperfect by the Nazi regime.

It’s even harder to total the victims that didn’t die. Instead, those who lived over a decade living in unimaginable fear after surviving concentration camps and the poor living conditions in Jewish ghettos, as they became known.

The children of those survivors, who have lived lives similarly affected by this genocide and the PTSD it has caused, will also be difficult to estimate. However, it’s likely that multiple generations have been altered by the Holocaust.

Academia has studied the effects of trauma on mothers and have established a theory that, when a mother’s life has been so altered by fear, their DNA can be affected. Physical traits are passed along to their children and can be observed and compared to others who are also second-generation survivors of trauma. This can even be studied with animals.

“You can see this in cows,” Clementi said. “If a calf witnesses the murder of its mother, the stress can alter it for the rest of its life.” High-anxiety environments that impact a mother can also affect the behavior of her offspring and their potential for growth.

Psychologists have observed that children of Holocaust survivors share similar personality traits, regardless of where they live or where they’re from.

Surrounded by numbers

Clementi grew up in the 1970s in Rome near, what has since been coined the Jewish ghetto, during the Holocaust. Throughout Clementi’s life, the echoes of the ghetto were everywhere, with the symptoms PTSD of second-generation survivors not far behind.

“From a Jewish point of view, Europe is a cemetery,” Clementi said.

As a child, she saw old graffiti and paintings on walls of swastikas and anti-Semitic messages. She felt surrounded by the Holocaust and its survivors.

“It bothers you, it humiliates you, but you live with it as though it’s a natural part of life,” Clementi said.

“There were these elderly people, at the time, that I’m sure were probably only in their 50s, but to me as a child they were ancient, that walked around with these numbers tattooed on their arms,” Clementi said. “If you asked, adults would tell you. They would tell you who these people were, and how many people in their family had died. There were little traumatic things we would see and talk about all the time.”

People she loved and grew up with were survivors of this massive genocide. As a child, all she wanted to do was take their pain away.

“If I could’ve only gone back to take away their suffering,” she said. “If I could only take that away from them. If I only could set the clock back and change things for these people. Which is a stupid thought, I know, but I was young.”

Clementi fondly remembered a woman who worked downstairs from where she lived. The woman cooked homemade pasta, and was so warm and enormous, but had a prominent tattoo that stuck out on her arm. The reminder of the Holocaust was always there.

The Star in the room

Even though she was Jewish, everyone around her seemed to be white, Italian and Catholic. The Jews had been in Rome since the Roman times, but the Fascist background of Italy was felt sharply by Clementi. She felt it was still the land of Mussolini.

“When I was 8 years of age, my uncle who ran a jewelry store gave me a golden Star of David,” Clementi said. “It was beautiful and I felt he was so excited to give it to me. No one ever told me not to where it, but I was aware that no one else was [wearing the Star of David].”

Being Jewish in Rome was never difficult for Clementi as a young child, but in middle school it became a problem. She felt she was a popular girl, and was really friends with everybody, but she had a few bullies. When she least expected it, slurs would come out.

“A boy beat me up. I mean he broke an umbrella on my head, and said a number of anti-Semitic things,” she said. “But when my parents came to talk to the teacher, she just said “Oh, he has a crush on her.’”

Disappointed by the anti-Semitism and sexism she was increasingly witness to in her hometown, Clementi took her studies abroad. She was in search of a place where she could feel comfortable and continue her studies.

She spent her academia focused on Jewish studies and the Holocaust. She studied in Poland, Israel, and at Brandeis University. However, that feeling of being the “other” always followed her.

“When I was abroad, it really became apparent,” she said. “Your best friends, the people you eat with and spend your life with-your intimate friends- would still joke or make slurs about being Jewish. When those lines come out, you feel how they look at you differently.”

Despite the discrimination, Clementi continued on. She joked that her life journey is very geographical – almost like her own Ulysses epic.

“I went on this life-long journey trying to find a place for myself where I could be who I am, do my work and at least feel comfortable and not feel threatened,” she said. To escape the misogyny and anti-Semitism of Europe, Clementi decided to move to America.

“I had a very strong feeling I was not going to move back,” she said. “My parents asked how long I’d be in America, and I said, ‘Maybe life?’

Clementi credits the support of her parents to much of her accomplishments in life. Their encouragement and support through her academia were uncommon in Italy. They pushed her to go for anything and everything she wanted to do, even though she was a woman and an only child.

“My mom told me to just do anything I wanted, and demand for it. I had an entire world around me telling me otherwise, but the support of my parents was everything,” she said.

After studying at Brandeis University, Clementi moved to New York and worked various jobs, including teaching Columbia University. In fact, when Clementi was offered a job at the University of South Carolina, she recalls looking the city up on a map. “I had to look it up! I really had no idea,” she said laughing. Despite this, she grabbed her cat and violin and drove to Columbia.

“I realized that what I did was more important than where I did it. In my 20s and 30s, it had to be New York. I had to be in the center of the world,” she said. “In my 40s, I realized I really wanted to devote myself fulltime to writing and for time to myself. In New York you don’t have time for yourself, forget about it.”

Clementi Today

Through her studies, and through her teachings, no matter the name of the course or the subject matter, Clementi has carried one theme throughout her life: to be open to the idea of the “other.”

“We have the capacity of overcoming our egos and selfishness, to look another being in the eyes and recognize the importance of their existence,” she said. “There are things in this world so much bigger than our individual singularity. Things like the environment and peace, and they are worth our lives. If we could spend our lives fighting for things that make everyone’s existence better, that’s a life worth living.”

Clementi defines the “other” as anyone, or anything, that is different than your immediate life. It’s minorities, and animals, and even the climate.

“Everything is profoundly connected,” Clementi said.

Currently, Clementi is working towards studying the connection between genocides and ecology. She is researching similarities between victims of genocide and victims of ecocide.

Clementi is also studying the long-term effects of the Holocaust on the Jewish mental and physical landscapes of Europe.