After months of debate, Indian Land voters voted no to incorporation and has decided to leave its governing to Lancaster County.

The map of the proposed town of Indian Land greeted voters as they entered the polls at Pleasant Valley Methodist church.

Sings of a growing area is the building site for the new high school along U.S. Highway 521 towards Lancaster. The county approved the new school to meet the demands of overcrowding at the current Indian Land high school, which opened in 2007.

The small South Carolina community of Indian Land rejected an incorporation effort last month, choosing to continue letting the Lancaster County government dealing with the heavy growth from metropolitan Charlotte, just north of the Carolina border.

“Incorporations are not that common in South Carolina, so that is not surprising,” said Jeff Shacker, the region’s field services manager for the Municipal Association of South Carolina that represents the 271 incorporated municipalities in the state. “But we did not see this wide of a margin coming.”

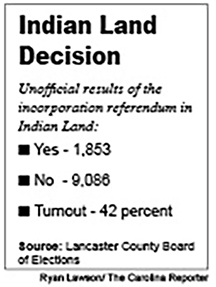

The unofficial results revealed Indian Land went against incorporation by a whopping 83 to 17 percent in the March 27 referendum. Turnout for the vote was at 42 percent as nearly 11,000 residents casted ballots. The referendum was defeated in every precinct in the area, including a shutout from Van Wyck’s 79 registered voters.

Van Wyck, a town of fewer than 1,000 people, sits south of Indian Land and north of Lancaster. The town is rural, almost all farmland. The Indian Land incorporation effort wanted to cut into Van Wyck and bring it within the town of Indian Land. When the Indian Land incorporation effort began, Van Wyck’s residents themselves quickly incorporated to stay out of the potential limits of the Charlotte suburb. Van Wyck then annexed land towards the north, mostly farmland that also did not want to become part of the town of Indian Land.

It works for Van Wyck, but it makes a future potential incorporation of Indian Land more problematic.

“The Van Wyck annexations will cause more issues,” Shacker said. “The land area they have added would have to be excluded in future proposals. That would have a major impact on the area of incorporation.”

“The size of the incorporated area was too much, almost 80 percent farmland, “said Lancaster County Councilman Brain Carnes, who represents Indian Land in the seventh district of the county. “There was strong belief the budget was not going to work and that the taxes were going to come.”

The failed proposal included 58 square miles with a $7.7 million town budget. Under those circumstances, Indian Land would have been the fifth largest city in South Carolina in terms of land mass. With such a large land area and a population of around 30,000 people, the budget was a big talking point in the months leading towards the vote.

“It was just a bad plan across the board,” said Mike Neese, an organizer of No Town of Indian Land, which lobbied against incorporation. “We knew this two years ago. It was a bad plan with bad leadership that tried to divide the community. We just told folks the truth and let them decide, and they sure did.”

Now that the incorporation effort has been defeated, Lancaster County will continue to provide services to Indian Land and control its governance. The county council of seven members will be tasked with continuing to control the growth of the community as they have done in recent years.

“The growth came when the county approved about 16,000 homes to be built in Indian Land from 2008 to 2012,” said Carnes. “Since then, we have only approved around 5,000, so we are controlling the growth.”

A driving factors of the mass approvals a decade ago was to help the county recover after the Springs textile plant, once the largest employer in Lancaster, closed its doors. With that now in the rearview mirror, the county has worked to control the growth of the area. The community will also continue receiving services from the county, something that could have led to hiked taxes under the incorporation effort.

“We already have everything from the county,” Carnes said. “Why pay for more?”