Isaac Woodard, center, is supported by heavyweight champ Joe Louis, left, and Neil Scott at the Hotel Theresa in New York City. Taken on Aug. 9, 1946, this photograph shows Woodard just six months after the brutal beating that left him blinded. (Source: Ossie LeViness/NY Daily News)

BATESBURG-LEESVILLE –“He helped defend his nation from a fearful enemy, came home to find that he still wasn’t free.”

These lyrics from Angela Easterling’s song “Isaac Woodard’s Eyes” were a grim reminder to those who gathered in the small town of Batesburg-Leesville of the vicious attack and blinding of a black Army sergeant returning from World War II. Woodward, who was passing through on his way home from the Pacific, was beaten by police and his eyes gouged out in what is considered one of America’s worst racially-motivated attacks.

The community came together Saturday to unveil a plaque memorializing Woodard’s life and remember how his story sparked social change throughout the country during the Jim Crow era, when the South was strictly segregated. Hundreds of people gathered in downtown Batesburg-Leesville to recognize his story.

Andy Duncan, who is white, spent much of his early life in Batesburg but didn’t hear about Woodard’s story until this century. He says that it’s time to stop covering up the truth from people.

“The blinding of Isaac Woodard was a crime, but a far graver crime would be to continue to blind our children and to blind ourselves,” Duncan said.

Robert Young, a nephew who took care of Woodard after the attack until his death in 1992, made the trip from New York and was surprised at how many people showed up to honor his late uncle.

I’m truly overwhelmed,” said Young. “I just had no idea what to expect. I came down here, but I thought it would be something relatively small.”

Young also said that if Woodard was alive, he would likely have mixed emotions.

“It would’ve been sweet [and] sad for him,” Young said. “To know that he was a part of getting this monument up and I’m happy to be a part of it.”

On Feb. 12, 1946, Woodard, a 26-year-old African American World War II veteran, was honorably discharged from the Army and was making his way home to see his family in Winnsboro, S.C. on a Greyhound bus.

Soon into the ride from Georgia, Woodard asked the bus driver if he could use the restroom. The white bus driver initially refused his request, but later in the trip he begrudgingly stopped in the town of Batesburg so Woodard could use the restroom.

The bus driver, still furious over having to stop and reportedly not being addressed “sir” by Woodard, told the white police chief of Batesburg, Lynwood Shull, about Woodard’s behavior. Shull and a few other police officers forcibly removed Woodard, who was still in his Army uniform, from the bus. Inside the jail, Shull brutally beat the WWII soldier, permanently blinding him.

The next day, Woodard was convicted of drunk and disorderly conduct. He didn’t receive any medical attention for three days after the attack and his family did not find out about the attack until three weeks after it happened.

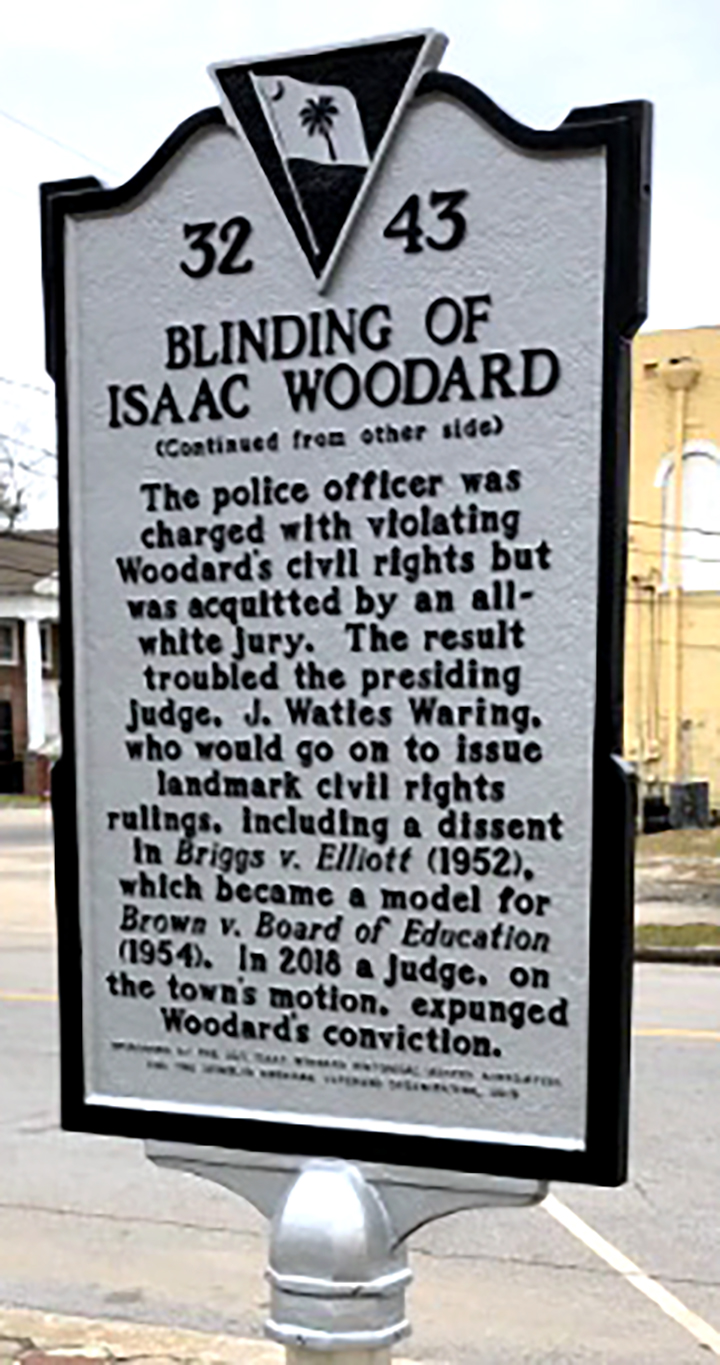

The attack on Woodard garnered national attention and outrage from both President Harry Truman and U.S. District Judge J. Waites Waring, who presided over Shull’s federal trial. In response to the lynching, Truman formed a Council on Civil Rights and issued Executive Order 9981, which desegregated the military in 1948.

Waring, the son of a Confederate soldier, presided over Shull’s case where an all-white jury found the Batesburg police chief not guilty of all charges. The jury only deliberated for 30 minutes. Waring believed Shull to be guilty, and soon became a civil rights advocate and a key figure in dismantling school segregation in the South.

It was important to honor Woodard, according to Batesburg-Leesville Mayor Lancer Shull, who is no relation to the former police chief.

“The importance in the community is to just to honor a soldier, to honor an African-American hero who’s from our town that was forgotten,” the mayor said. “This moment was the cornerstone for the civil rights movement in our country.”

It was also important to Mayor Shull that he acknowledged what happened to Woodard.

“It’s like ripping off a Band-Aid at times,” Mayor Shull said. “We have to expose and take a look at some of those atrocities that did happen throughout the South and talk about them.”