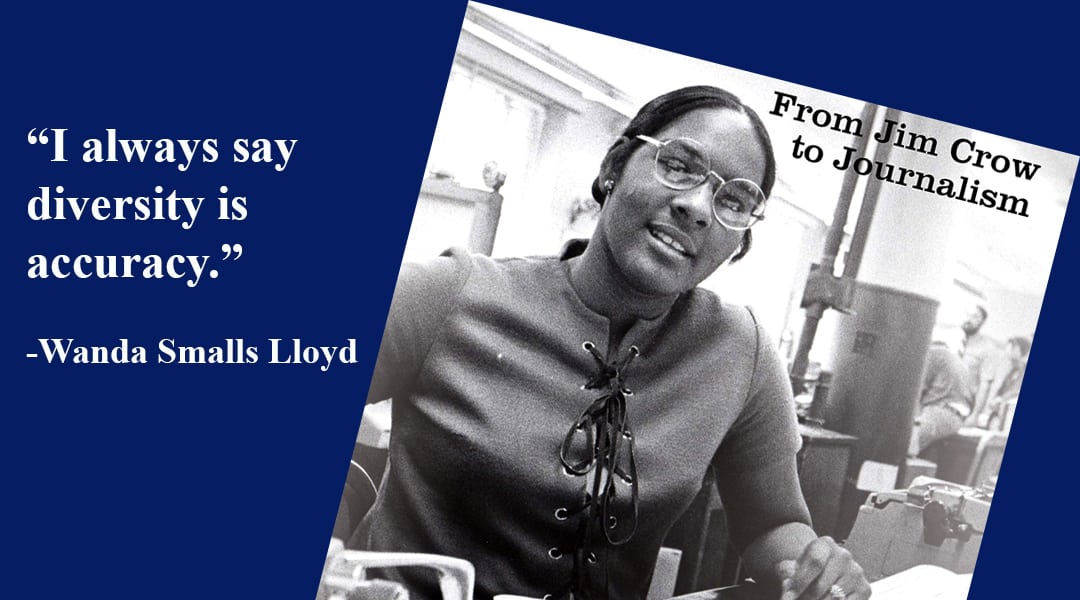

Wanda Lloyd wrote a memoir that details growing up in the Jim Crow South and becoming a top news editor and champion for diversity.

For Wanda Smalls Lloyd, simply walking into a newsroom in 1972 was enough to change the American journalism industry.

She broke barriers as a female African American editor at newspapers run by white males. She changed the way journalists reported on black communities. She hired black reporters. She made sure white reporters understood the rich histories of minority communities.

“There was nobody like me as an editor in newsrooms at the time,” Lloyd said. “It was lonely and I was young, so I wasn’t able to take care of the change then.”

Year by year, she rose through the newsroom ranks and discovered that she could wield far more influence as a managing editor than an on-the-ground reporter.

She was senior editor for USA Today and held editor roles at the Washington Post, the Atlanta Journal, the Miami Herald, the Greenville News and the Montgomery Advertiser. Between editing jobs, she became the founding executive director for the Freedom Forum Diversity Institute at Vanderbilt University and the journalism department chair at Savannah State University.

“As we’re not just reporting the news, as we’re directing coverage of the news, we can have a real impact,” Lloyd said.

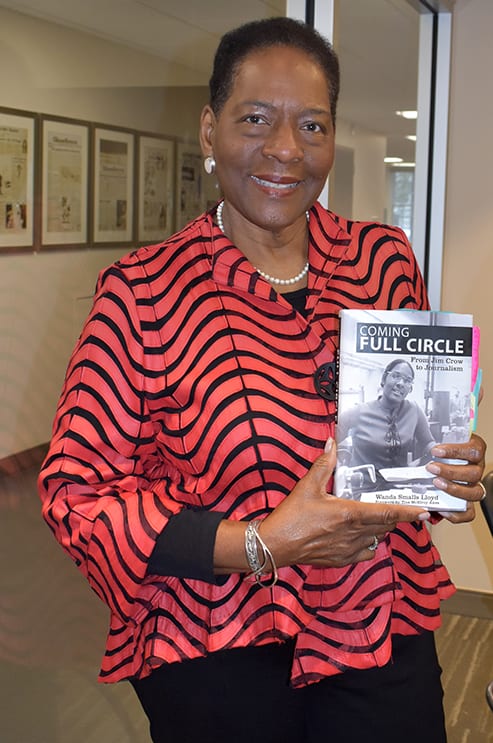

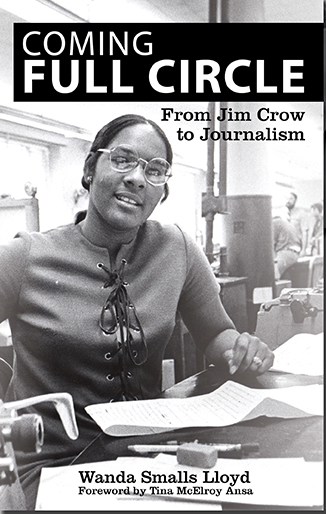

She has written about that journey in a new memoir, “Coming Full Circle: From Jim Crow to Journalism” (NewSouth, $26.95). It details her life growing up in segregated Savannah, Georgia, and her wide-ranging career as a newspaper editor in a largely white, male industry.

At the Greenville News, Lloyd created initiatives to help reporters change the way they thought about black neighborhoods.

She once hired a bus to take newsroom journalists on a tour of West Greenville, a predominantly black community that white reporters dismissed as crime-ridden. Lloyd helped them see that the neighborhood was also home to pastors, educators, doctors and philanthropists.

Inside the Greenville newsroom, Terry Manning became a colleague and friend, eventually working with her at the Montgomery Advertiser and Savannah State University. Only later, did he realize her stature in the news business extended far beyond South Carolina.

“I just thought she was a really impressive black woman in the newsroom,” said Manning. “It was only later that I caught onto, ‘Oh, this is Wanda Lloyd.'”

Throughout her 45-year career, Lloyd advocated for the creation of professional organizations like the National Association of Black Journalists. NABJ continues to encourage minority journalists to claim positions of power in newsrooms and to have a greater voice in journalism. She was recently inducted into the organization’s Hall of Fame.

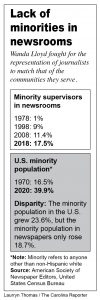

Although there are more minority journalists today, Lloyd said they are not rising to management positions in the top of the field.

“Diversity, it wasn’t the first casualty, but it was an early casualty in the compression of the industry,” said Manning.

Lloyd said no one anticipated the industry-rocking shift to digital media which hurt diversity and damaged much of what she had been fighting for for so long.

“When I retired in 2013 from my last newspaper job, there were four African American women who were leaders in the newsroom in newspapers,” Lloyd said. “When I left, there were three.”

Though Lloyd grew up in the segregated South, she came from an upper-middle class family. She “came out” as a debutante much like the more well-known white debutantes of the time, although she said the rituals of her community mostly went unnoticed.

Lloyd was the third generation in her family to attend Spelman College, the storied Atlanta institution that has educated hundreds of prominent African American women. There, she was the editor-in-chief of her school newspaper. Spelman did not have a journalism program, so Lloyd had to take classes across the street at Clark College.

“I’d never seen anyone on TV, never, who was African American and female, in terms of journalism,” said Lloyd.

Her first job was in Providence, Rhode Island, as a copy editor.

All of the other women in the office were known as dictationists, while Lloyd was an editor. When women in the office eventually asked Lloyd how she’d gotten this position, they were shocked to discover she had graduated college. Most men in the office had not even gone to college. It was tough to secure an apartment and her neighbors weren’t quite sure what to make of her.

“Here I was, worlds away from the Jim Crow South, but the perception was that I was a maid or a nanny,” said Lloyd about her experience sharing a home with white co-workers in Rhode Island.

Revolutionizing the workforce was not something Lloyd had to focus on at first. Her seat at the table alone was a major accomplishment.

Revolutionizing the workforce was not something Lloyd had to focus on at first. Her seat at the table alone was a major accomplishment.

Earlier this month, Lloyd visited the University of South Carolina journalism school on a leg of her book tour. Kenneth Campbell, a UofSC mass communications professor, had similar experiences as a beginner reporter in Niagara Falls, New York, and the only minority hire in the newsroom. Even though this history seems fairly recent, Campbell said it is still significant.

“We still only have had five or six African American women who have risen to the level that she has in newspaper journalism. That’s incredible,” said Campbell.

Manning said the biggest lessons he learned from Lloyd were the importance of hard work and how to be “gracefully honest” at work. She led with a gentle authority, even when dealing with difficult employees and a child and husband at home. Lloyd worked so hard that she could never seem to stop; she came out of retirement multiple times.

“She probably works harder than anyone you know,” Manning said. “I keep telling her, look, I can’t come to any more of your retirement parties because I’m running out of things to say about you!”

As an editor, Lloyd was known for sending emails at all hours of the day and night. Now, at 70 years old, Lloyd drives herself across states for her book tour. Along with her hardworking reputation, people who know Lloyd describe her as an “encourager” focused on supporting those around her.

“A lot has changed now. Don’t think I’ve been sitting around here for 45 years and not changing anything!” Lloyd said.