A statue of Confederate General Wade Hampton dominates the south side of the State House grounds.

The South Carolina’s State House is a three-story, neo-classical structure of blue granite, marble and iron that stands at the center of a 22-acre complex in the heart of Columbia.

Today, the State House and its seven surrounding building and 30 monuments are the focal point of a new tour being offered Historic Columbia Foundation.

Robin Waites, executive director of Historic Columbia, said the tour, which has been available since October, seeks to create dialogue about the past and how it’s perceived today.

Waites thinks there are a lot of people who don’t realize the people that are represented in some monuments and what it says about the state of South Carolina.

“So, the questions that we’re asking have to do with whether or not these monuments represent us, today,” said Waites.

A broader debate on the removal of monuments celebrating some state’s Confederate past has been common around the country for the past few years.

Until 2000, the Confederate battle flag was flown with the American flag and the South Carolina flag atop the Statehouse dome. It was moved to a location in front of the building at the Confederate Soldier Monument under the Heritage Act of 2000. The flag had a permanent home in that location on the Statehouse grounds until July 10, 2015, when then Gov. Nikki Haley called for its removal.

It was removed after convicted killer Dylann Roof walked into the basement of Emanual AME church in Charleston in June 2015 and killed nine African Americans during a Bible study. The tragedy sparked nationwide debate over displaying the Confederate flag after it was discovered the shooter posted messages of white supremacy and photos displaying the flag.

Several of the monuments celebrate symbols of the past that don’t align with the views of many South Carolinians – Confederate figures that still stand tall four years after the 2015 Charleston church shooting. According to Waites, these tours are a natural progression that follow a nationwide movement to either move controversial monuments, or place interpretive signage next to them.

Waites says the tours aren’t offered in hopes of taking down old monuments but so that people can begin to discuss what, if anything needs to be done about them.

“People might say ‘we’re perfectly happy with these things representing us, and we don’t want anything to change.’ There may be people who say there are opportunities to tell a more complete story with interpretive signage, which a lot of communities are doing,” she said.

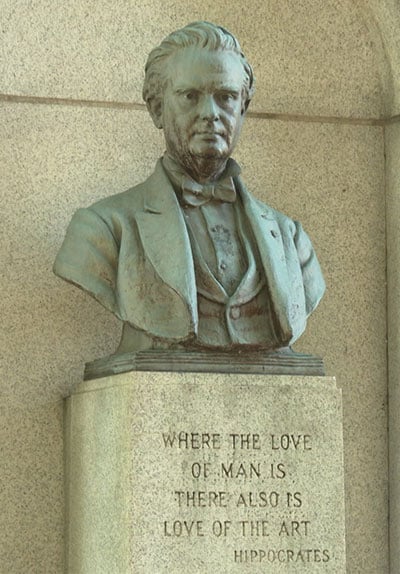

Some of the monuments, such as those of Confederate General and Gov. Wade Hampton and Dr. J. Marion Sims, have created controversy and calls to have them removed. Hampton led the largest cavalry regiment during the Civil War and was elected governor in 1876 as a “Redeemer” who pledged to end the federal Reconstruction laws that were imposed following the South’s defeat. His election included intimidation of black voters.

Sims is a South Carolina native who is considered the “father of gynecology.” However, his experiments on enslaved black women without the use of anesthesia prompted the removal of his statue in Central Park in April 2018.

Another controversial figure is Benjamin Ryan “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman, a 19th century governor who promoted himself as a representative of the common man. But he was also a well-known white supremacist. Tillman happens to be one of the first things visitors see on the north side of the State House building.

The question surrounding Tillman’s prominence on the State House grounds is one of the things Waites and Historic Columbia is asking participants.

“Once you know that about that person, do you think that it’s appropriate that he would be the first person you would see when you walk onto the State House grounds?” Waites asked. “Does that mindset and those values represent us as South Carolinians today?”

Some South Carolinians are torn about Tillman’s role in the history of the state and whether or not they would support removing his statue.

“He’s a very polarizing figure because he greatly hurt African American people. He had many racist policies that hurt them,” said Griffin Keeffe from Elgin. “But he is a key figure in our history. So, it goes hand in hand, but I feel like there should be an asterisk next to his name describing what he’s done wrong and what he’s done right.”

Keeffe believes that it’s important to understand the state’s history and individual roots, and understand where we come from because these monuments are from a point in our history that we shouldn’t forget – good or bad.

Despite these tours providing context and starting an important conversation, it might be a lot longer before any changes are made.

The Heritage Act was adopted by the General Assembly in 2000, when the Confederate flag was moved from the State House dome to the Gervais Street side of the building. The law requires a two-thirds majority vote by members of the general assembly to remove or change and historic monuments or markers.

There are still two more tours available before the end of the year on Dec. 7 and 15. For booking information visit historiccolumbia.org or email reservations@historiccolumbia.org. The tours are free and open to the public. For a self-guided tour, visit historiccolumbia.org.