Fourteen-year-old Gabriella Martin said her generation doesn’t want the oil jobs one of the offshore drilling bills promises. “We want 21st century jobs powered by wind and solar,” Martin said.

Imagine whales and dolphins washed up on the shores of South Carolina’s coast.

Titans of industry and S.C. political heavyweights weighed in at a legislative hearing Wednesday, but it was the words of 14-year-old Gabriella Martin that resonated during the three-plus hours of testimony.

Martin, an eighth grader from Pawley’s Island, spoke in support of a measure that would ban the selling of permits for onshore infrastructure for petroleum companies, a crucial component for offshore oil rigs. She said the lawmakers who support offshore drilling won’t be around to witness marine animals go deaf or die from seismic blasting or clean up in the case of an accident or spill.

“But I will be here,” she told the Environmental Affairs House subcommittee.

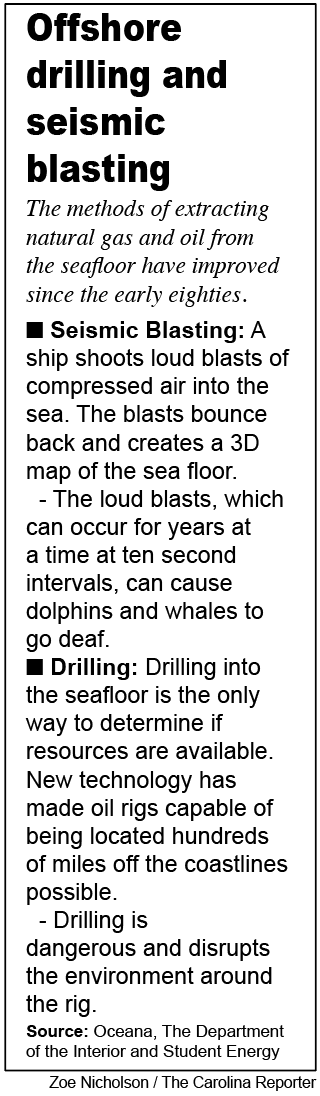

Martin said the potential damage from seismic blasting is a threat to marine life, particularly whales and dolphins, off S.C. coasts. Seismic airgun blasting is a way to map out the seafloor to identify potential oil and gas wells. It’s done by shooting incredibly loud sound blasts into the sea from the bow of a ship every 10 seconds for 24 hours a day. In Louisiana, seismic blasts have been administered at this rate for nearly four decades.

Resolutions have been passed by every coastal county except Beaufort and every city along the coast against offshore drilling. According to a poll by Winthrop University, more than 50 percent of South Carolinians oppose offshore drilling. Gov. Henry McMaster has also stated his opposition to off-shore drilling.

The anti-drilling bill would ban state agencies from granting permits to petroleum companies to build onshore infrastructures in South Carolina. An opposing bill would allow agencies to grant permits.

Both bills were approved, but the subcommittee failed to recommend one bill over another, a rarity. Neither are expected to be acted upon this session, although that has not lessened the intense interest in the issue.

Rep. Mike Burns, R-Greenville, is the sponsor of the pro-offshore drilling bill. He cited the possibility of 34,000 jobs that would flood into the state if oil infrastructure were allowed.

But Peg Howell, a former petroleum engineer and staunch opponent of S.C. offshore drilling, said her experience working in the Gulf of Mexico showed that Burns promise of jobs is unfounded.

“These jobs will not be local jobs,” Howell said. She explained rig jobs are highly skilled positions, and those in the industry are “nomads” who work on an oil rig for a few weeks before moving on to another job.

The U.S. is a top exporter of crude oil. Since the “shale revolution” in 2008, the U.S.’s export levels have peaked to amounts higher than the pre-1970 oil embargo. In February, exports reached as high as 3.6 million barrels a day.

“We are awash in oil and gas,” Howell said. She added that the oil fields in West Texas and New Mexico, where most of the crude oil is being produced, is making enough for the whole country.

Howell added that since the rigs would be in federal waters, three to 200 miles off the coast, the revenue from oil production would not be taxable by the state. Proponents of drilling says there is the possibility of tax revenue from the oil infrastructure, but President Trump has said he is not open to allowing states to receive offshore revenue.

“In order to create a revenue stream, that would take an act of Congress?” Rep. Lee Hewitt, R-Georgetown, asked Howell, who is his constituent.

Howell nodded, “That’s correct.”

Mark Harmon, the executive director of the South Carolina Petroleum Council, said he had a “gut feeling” the act of Congress Hewitt referenced would eventually pass. President Trump would still have to sign the act into law if it were to pass.

The State newspaper reported that the American Petroleum Institute, which Harmon works for, has spent thousands of dollars lobbying at the State House since last year.

The main concern about offshore drilling was the potential impact of the state’s $20 billion tourism industry.

Queen Quet, the chieftess and head of state for the Gullah/Geechee Nation, spoke for the first time before the state lawmakers to express her concerns over the potential of offshore oil.

“It is the richness of Gullah/Geechee culture that draws millions of tourists to the coast per year,” Quet said. The chieftess and computer science engineer held up a fishing net to illustrate the importance of the coast’s sea islands and seafood industry to the state economy.

Quet said her Gullah culture, an African American culture developed from four centuries of coastal living with African, American and Native American influences, is the driving force behind the tourism industry.

“We were the black gold of South Carolina. And we’re the only black gold you still need,” she said.

John Durst, president and CEO of the South Carolina Restaurant and Lodging Association, painted a dire picture for the state’s lucrative tourism industry should off-shore drilling proceed.

“[We have] strong concern that any offshore drilling would put the state’s tourism industry at risk,” he said. Durst said SCRLA opposes “offshore drilling in any manner.”

Many members of the Charleston delegation attended the meeting to express their opposition to offshore drilling, particularly in regards to the possible loss of revenue if tourism were to be affected by drilling.

“I know firsthand the revenue [from tourism] and what it means economically to the city,” Rep. Mike Sottile, R-Charleston, said of his hometown Isle of Palms. Sottile added that if the revenue were to be disrupted, “we wouldn’t have the ability to buy fire trucks anymore.“

Another Isle of Palms elected official, Mayor Jimmy Carroll, spoke on behalf of the beachfront community.

“Oil and water don’t mix,” Carroll said.

Another topic of question was the reliability of testing and drilling technology, particularly in the wake of accidents like the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Harmon said improved technology for rigs and stricter regulations have made offshore drilling safer and more reliable than it was 30 years ago. But when pressed by Rep. Michael Rivers, D-Beaufort, about the “infallibility” of the rigs, Harmon admitted they are manmade structures, and therefore not exempt from spills or accidents.

Rivers then asked Harmon whether a mistake would be “catastrophic” to the state’s seafood industry, a $2 billion industry. Harmon would not give a definitive answer.

“You can’t answer the questions, and you’re in the business,” Rivers rebutted.

After a contentious meeting and a last-second amendment proposal to the anti-drilling bill by Burns, the pro-drilling bill’s sponsor, both bills passed to the full House Agriculture Committee. Burns voted yes for both bills.

The bills did not make the crossover deadline to the Senate. This means they will not be voted on and potentially signed into law this legislative session, but can be voted on next session, which will be the second of a two-year session.

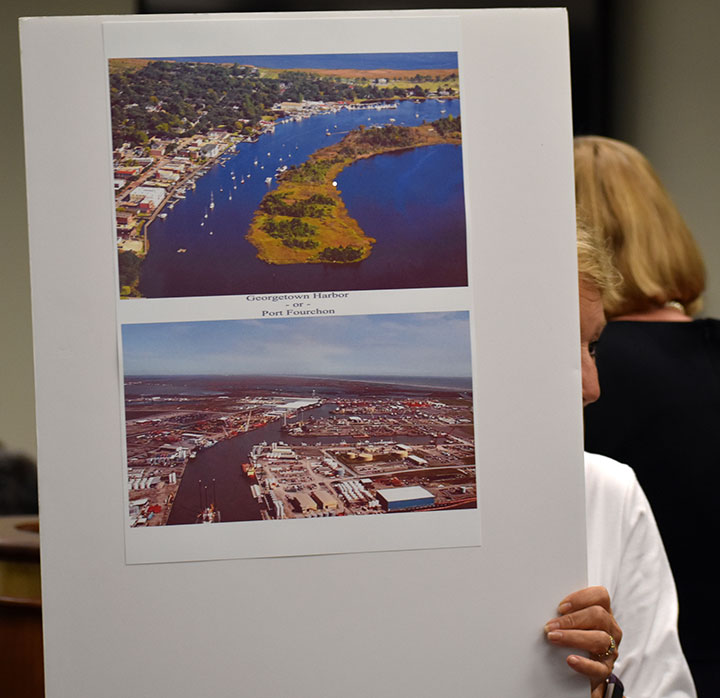

The House Environmental Affairs subcommittee met Wednesday to hear testimonies on two opposing bills on offshore drilling. Opponents of offshore drilling held up a sign to compare Louisiana’s Port Fourchan, below, which has infrastructure from offshore oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico, to Georgetown Harbor on the coast.

Rep. Mike Burns, R-Greenville, is a co-sponsor of a bill that would allow permits for onshore oil infrastructure along South Carolina’s coast. The only lawmakers at the meeting who supported offshore drilling were from the Upstate and Midlands.

Queen Quet, chieftess and head of state for the Gullah/Geechee Nation, said her people were a major economic force in the Lowcountry, where millions of tourists travel every year to learn about the sea islands’ culture that descended from African slaves.

Mark Harmon is the executive director of the South Carolina Petroleum Council. Of the three-plus hours of testimonies given at an environmental affairs subcomittee hearing at the State House Wednesday, Harmon was the only pro-drilling speaker.