Three students were killed and 27 wounded on Feb. 8, 1968, when state troopers fired at protesting students at S.C. State.

Credit: Cecil Williams

Whites could bowl at Orangeburg’s All Star Bowling Lane but students at S.C. State had to drive to Columbia to find open lanes.

Credit: Cecil Williams

State troopers were out in force to monitor escalating protests at S.C. State in February, 1968.

Credit: Cecil Williams

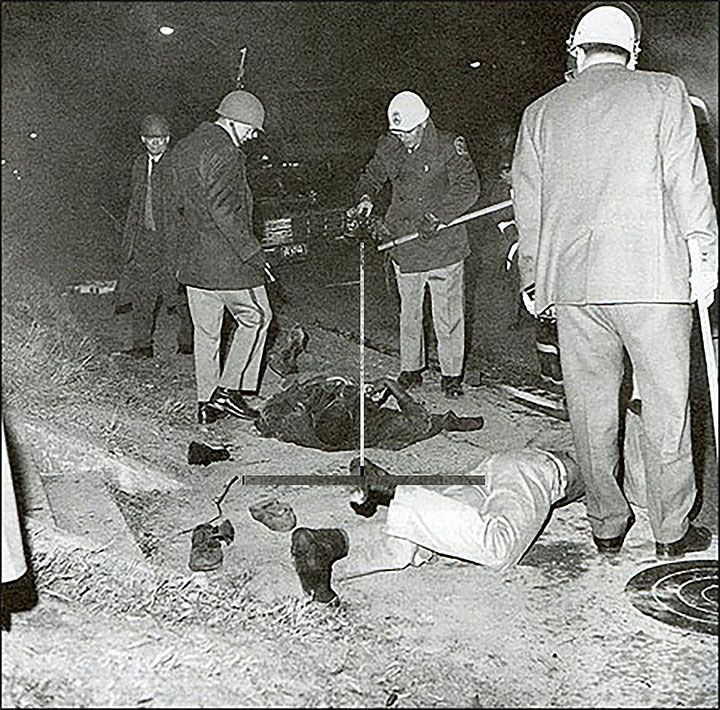

State troopers looking over the wounded following the Feb. 8, 1968 shooting that came to be known as the Orangeburg Massacre.

Credit: Cecil Williams

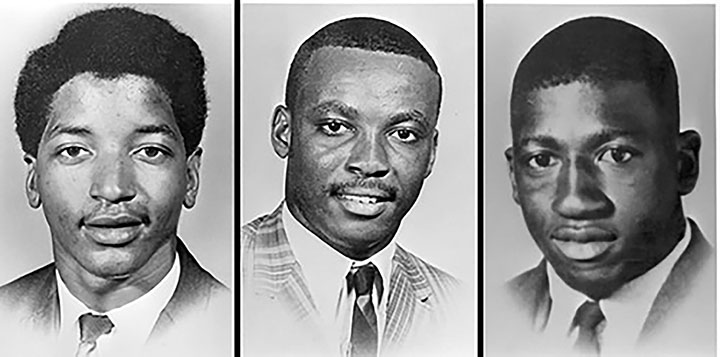

Three African-American students, Henry Smith, Samuel Hammond Jr. and Delano B. Middleton, were shot to death during the Orangeburg Massacre.

Jordan Simmons III remembers the night 50 years ago when he was shot in the neck by state troopers as he ran from a civil rights protest at South Carolina State College.

He doesn’t dwell on the events of Feb. 8, 1968, but the shooting that came to be known as the Orangeburg Massacre comes to mind every now and then. He would prefer to spend his time doing things that truly mattered and bring positivity to his life.

“I just can’t stay focused on it, because if I do that, other things that need to get done will be most difficult for me,” Simmons said. Simmons is a 71-year-old retired lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army, currently living in Arlington, Virginia.

“I do think about it, because I hurt,” he said. “It still bothers my arms from time to time and my nerves down to my hand.”

On the night of Feb. 8, students were massed at the bottom of campus to protest the segregation of Orangeburg’s only bowling alley. Then Gov. Robert McNair had placed state troopers on the scene because there had been incidents at the bowling alley throughout the week two days prior.

African-American students protested by causing a bonfire on campus. Firetrucks arrived as the troopers monitored the chaotic scene. According to accounts, one of the troopers were struck in the face by a banister that was thrown by one of the students. Warning shots were fired by a patrolman, then the other officers began shooting. Students began running away in fear and as they did they were shot in their sides, backs and their feet.

Three African-American students died: Henry Smith, Samuel Hammond Jr. and Delano B. Middleton. Smith and Hammond were students at S.C. State, and Middleton was a high school student.

At least 27 more people were injured when state troopers fired buckshot at the students as they turned to flee. Simmons was shot in the neck as he was on the ground trying to crawl to safety. He said he tried to cope with the pain, but there were some things he could never come to terms with.

“As I began to heal, I’ve learned to live with it. I am not angry with what has happened … not anymore, but I am disturbed by the way in which the state has taken the attitude over the years,” Simmons said.

Simmons feels like the troopers stretched the truth by saying protesters fired shots at them during the riot.

“I’m definitely in disbelief that we were shooting at them and doing things to cause them harm — whatever we were doing did not justify them shooting at us. I can’t separate that,” he said.

Reporter and author Jack Bass wrote in his book about the Orangeburg Massacre, “Whether the state eventually provides restitution as the final stage of reconciliation, as Florida did more than a half-century after the destruction of the all-black town of Rosewood, remains to be seen.” And now, 13 years later, Bass feels the state needs to have a full investigation of a special council and provide restitution.

Bass was called onto the scene to report for the Charlotte Observer newspaper.

“I got a call that night and I came to the campus,” Bass said. “The patrolmen had these big batons the size of a small baseball bat and started beating students over the head. One student literally had his skull cracked and was taken to the hospital. Several were in overnight, some were treated and released.”

Last week, several hundred people gathered at S.C. State University for the 50th anniversary of the Orangeburg Massacre. Students sang and played music. Bass was in attendance, along with administrators and community members to help keep the legacy of the victims alive.

Bakari Sellers, Cleveland Sellers’ son, spoke at the memorial. Sellers was a civil rights activist who protested on S.C. State campus during segregation of the All Star Bowling Lane. He was shot in his left shoulder and served seven months in prison for engaging to riot.

“With tragic situations as such, you may feel guilty for surviving, you may feel guilty because you may have felt you may have caused someone to do something they shouldn’t have done for something you’ve said,” Simmons said. “A number of things could drive a person to feel that way.”

Although Simmons had a hard time moving on from such a disastrous moment in his life, the incident confirmed for him that injustice requires taking a stand.