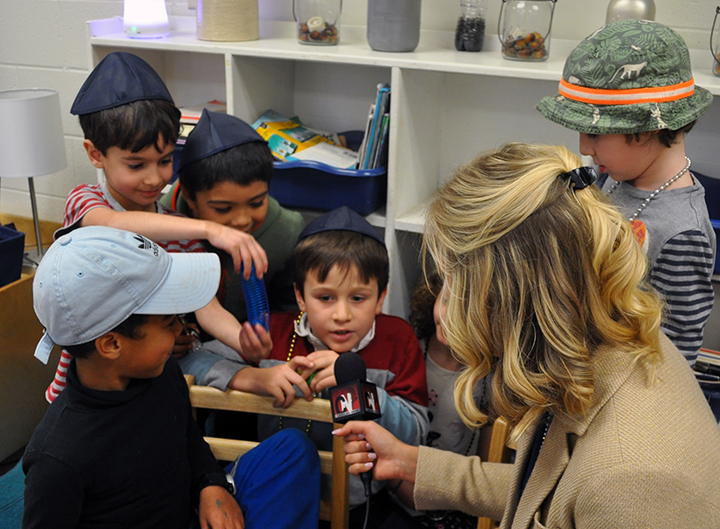

Young students at the Cutler Jewish Day School in Columbia talked about Passover with Carolina News and Reporter in 2019. The school, like others across the South Carolina, is closed now due to the coronavirus pandemic.

By LAURRYN THOMAS and McKENZIE LINDBERG

In Judaism, Passover celebrates and pays homage to the exodus of the Israelites out of ancient Egypt. Passover began with plagues, mass murder and deliverance from God. One of these things could be compared to what we are living through today with coronavirus.

“We’re kind of rocking with it. The Passover holiday kind of commemorates plagues and we’re in one now so we don’t really have to commemorate anything right now,” said Stanley Dubinsky, a linguist professor at the University of South Carolina.

Passover celebrations normally include a week of festivities with liturgies and preparation of traditional foods in large family gatherings. There is a divide in the Jewish community on how to honor this tradition in a pandemic.

“Rabbis tell people to celebrate and that may be impacted by not being able to come together. Some communities have advocated being on Zoom or something with your family members,” said John Mandsager, assistant professor of religious studies and Jewish studies at UofSC. “There are some difficulties in Orthodox Jewish communities that have traditionally forbidden the use of technology during this time.”

Mandsager also said that this year may put many Jewish families in a bind because of travel restrictions. Rather than celebrating a traditional Passover this year, many will find themselves celebrating with only their immediate family or using technology.

“I can’t imagine taking communion over Zoom. And some people are going to say that doesn’t feel right. Because part of any religious expression and religious tradition, whether it’s Christian, Muslim, or Jewish, is strongly communal,” Dubinsky said.

Though Dubinsky is not an Orthodox Jew, he still does not want to celebrate the holiday using technology. Dubinsky and his wife and daughter normally celebrate Passover with many other families in the Columbia Jewish community. While religious gatherings are still allowed in South Carolina, the Jewish community is social distancing.

“There’s a key component in Judaism “Pikuach Nefesh,” the principle of saving life, that all other rules, regulations, ritual practices are secondary to the primary concern that is not only to not endanger life but to save life, human life,” Mandsager said.

Another roadblock in celebrating Passover this year is the ability to find all of the traditional foods to eat at grocery stores. With governments telling citizens to not make many trips to the grocery stores and grocery stores selling out of items, this is a concern for some.

“Not only would it be sad if we did it together with just the three of us, but we can’t get the stuff that we need and so we just talked about it and said ‘you know what let’s not make a fuss out of it,'” said Dubinsky.

For observant Jews, rituals include a traditional Passover meal and the removal of leavened products from their homes. According to the story of the Israelites’ flight from bondage, Jews had to flee from their Egyptian masters before the household bread had risen.

The traditional Passover plate includes bitter herbs to represent the bitterness of bondage; charoset, a mixture of apples, wine and nuts to symbolize the mortar of the bricks they were forced to make; , and matzo for bread. On the first and second nights of Passover, Jews also retell the story of the Israelites’ exodus during Passover through liturgies at the table.

“Some people are worried about not getting all the traditional foods including matzo,” said Mandsager. “Then people have been falling back on that other ethical statement of we better stay safe so if we have to exclude some of the things, that’s going to be okay.”

This history of Passover derives from the deliverance of the Jews from slavery in Egypt in the 14th century B.C.

In the Hebrew Bible, the Torah, the story of the Israelites’ departure spans across three books – Exodus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The story tells of a hostile pharaoh who ordered the enslavement of the Israelites because the Egyptians saw them as a threat. He also ordered that every firstborn Israeli son be drowned in the Nile River.

One Hebrew mother hid her baby Moses in bulrushes, where he was rescued by the pharaoh’s daughter. He was adopted and raised in the Egyptian family. Once he became an adult, he learned of his true heritage and how horribly his people had been treated. Moses killed a Egyptian slave master and fled Egypt but received a command from God to return to Egypt to free his people.

The pharaoh refused to free the Israelites, and God released ten plagues on the Egyptians. The enslaved Israeli’s marked their door frames with lamb’s blood so that the angel of death would “passover” their household.

Scared of further punishment, the Egyptian pharaoh released all of the Israleites and Moses led them out of Egypt. The pharaoh, however, changed his mind and sent an army to bring them back.

When the Egyptian army found the Israelites at the edge of the Red Sea, God parted the sea, allowing the Israelites to cross, and then closes it, drowning the army.

Since then, people of Jewish heritage have kept the celebration of the Passover alive, even in times of war and pandemic. This year is no different, although Jews acknowledge that Passover is celebrated very differently this year.

“We have a range of responses this year to the primary goal which I hope we’re all abiding by which is to stay safe, stay home and not be vectors for the disease,” said Mandsager.