The road to addiction recovery is not an easy one, but with medically assisted treatment, 12-step programs and 28-day recovery programs there is help available.

The Detox

What does it feel like to die without dying?

An opioid addict experiencing withdrawal would be able to tell you.

It takes you to the brink of immeasurable pain with symptoms including uncontrollable shaking, fluctuating body temperature, vomiting, diarrhea, insomnia, agitation, depression and anxiety.

“Physically, you’re going to wish you were dead,” Brock Sansbury, 31, deputy director of the Courage Center and a recovered addict, said. “But mentally you know you’re not going to die from it and you know exactly what’s going to make you feel better.”

Prescription opioids and illegal hard drugs such as fentanyl and heroin re-wire the brain’s pleasure and pain receptors, causing extreme mental and physical dependency. The longer the user has been reliant on opioids, the worse the withdrawal.

To escape the unbearable symptoms, which can last anywhere from a few days to several weeks, many turn back to the drugs they were seeking refuge from, leaving addicts feeling the suffocating impossibility of getting clean.

“To wake up every day and have to go get high is a sad place to be in,” said Gabriel Mangold, 44, recovered addict and friend of Sansbury. “You’re waking up every day knowing ‘I’m in a lot of trouble. I need to stop this… after I get high.’”

Mangold and Sanbury took separate paths on their way to recovery, tangled routes that testify to the complexity of the American opioid epidemic and the turbulent debate over how best to help recovering addicts.

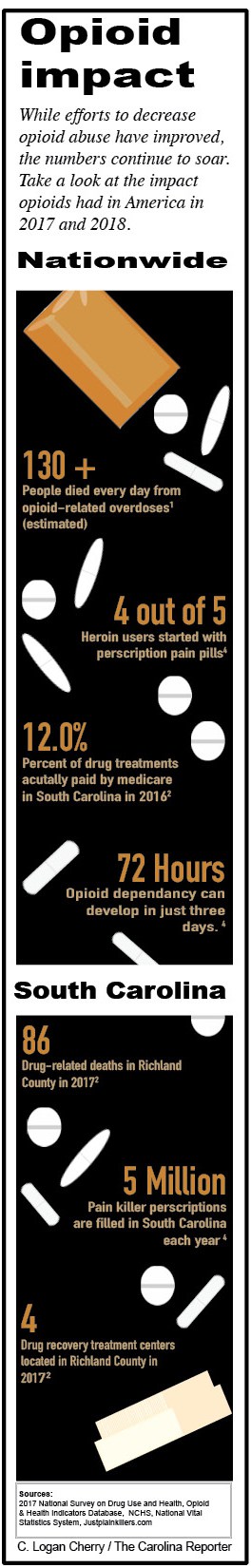

The 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that 11.4 million people misused prescription opioids in America.

The Natural Progression

Mangold doesn’t shake his legs nervously or fidget anymore. He lounges back on the couch, crossing his legs comfortably, revealing his bright-blue painted toenails. With his friendly, bellowing voice he finds a way to mix humor with painful honesty.

Now living in Irmo, South Carolina, Mangold grew up in what he describes as a loving, supportive family. His suburban high school experience in Los Angeles was typical of the early 90s, with some teenage experimentation with alcohol and drugs.

“It started off in high school as smoking weed and drinking alcohol,” he said. For most of his friends it stopped there. For Mangold, who describes himself as someone with obsessive, addictive behavior, “It ramped up a little bit with cocaine. Then it progressed to speed, which fueled my drinking.

“Evidently being drunk at work is an issue,” he remarked with a chuckle. “Finally, I began using pain pills as a way to not drink at work but maintain that mellow. I graduated to oxycodone and eventually, heroin.”

Sansbury’s story of building drug experimentation is similar to Mangold’s. The Columbia native describes being in 8th grade trying to smoke cigarettes and sneak alcohol from his unsuspecting parents.

He then graduated to smoking marijuana and eventually “any drugs you can find in high school.”

“Some of these things aren’t abnormal. I would argue that some are natural rites of passage in terms of growing up and being a teenager,” Sansbury explained. “But some people do it way more responsibly than others. Some didn’t search it out in every factor of their life as I did.”

On separate coasts of the United States, Mangold and Sansbury were unable to control their urges when it came to substances. It was never just one drink, it was drinking to get drunk. It was never just one hit or one pill, it became an every day thought-controlling obsession.

Sansbury then graduated to prescription opioids. His first experience with oxycodone left him sick, but the second experience left him addicted.

“The euphoric feeling I got with the second one was intense,” Sansbury said. “I had never experienced anything like it and suddenly I understood why people become homeless for it. I mean within five days, chemically and physically, I was already dependent.”

Something to Take the Edge Off

After two decades of drug and alcohol abuse, Gabriel Mangold was able to get clean thanks to a medically assisted treatment known as methadone.

“I always liked to party,” Mangold admitted, “But also when I put substances into my body, that fear and anxiety that I had felt ever since I could remember just went away.”

Mangold touches on the underbelly of the addictive drug industry and the dark secret they continuously try to hide. Drugs prey on those predisposed to anxiety and mental illness.

“If you’re already prone to depression and anxiety, and honestly just being an adolescent with emotions you’re not used to dealing with and your body is pumped full of hormones and life can be disappointing sometimes, suddenly you find something that relieves it,” Mangold explained. “The problem is that thing also causes it.”

Addiction, now recognized as a disorder by the American Psychiatric Association, is more than just a physical craving.

“I do believe it’s a health and mental issue. It’s insidious and I think some are more prone to it than others,” Mangold said.

The problem with admitting you have a problem

After getting a job as a DJ, Mangold found himself in a lifestyle that encouraged drug use. He slowly cut off his friends who disagreed with his opioid use and attempted to manipulate his family into assisting his expensive drug habit.

Sansbury found himself in a similar situation. His mother and grandfather had already decided it was time to step away, not able to watch him go down this path any longer. “My mom was like you’re either going to die, or you’re going to live, but we’re not going to watch you die.”

According to the Opioid and Health Indicators Database there were only four drug recovery treatment centers in Richland County in 2017.

Even though both Mangold and Sansbury could feel their lives spiraling they were too caught up in their addiction to escape it.

“I was busted, disgusted and could not be trusted,” Sansbury said, laughing.

One of the hardest steps to getting over addiction is the realization.

“It’s a slow burner. You don’t wake up one day like ‘Aw, I’m an addict,’” Mangold said, then, after a momentary pause, rethought his answer. “I guess you do, but you’ve already been an addict for a long time when that happens because there’s this idea of ‘Well, I can quit whenever I want.’”

It took Mangold two decades of drug usage to discover that he couldn’t quit because of the mental and physical dependency his opioid addiction created.

With a $1000-a-week drug habit he was struggling to afford, family that decided to “stop coddling him” and several attempts at quitting on his own, Mangold realized he needed to find a way out.

“There was this double thing where I couldn’t see it going on the way it was going, I didn’t want to use anymore, but at the same time I couldn’t see how I could not use,” Mangold explained.

He finally just googled “how to get clean,” and information for a methadone clinic popped up.

Medically Assisted Treatment: A Saving Grace or Devil in Disguise

“It literally saved my life,” Mangold emphasized.

Methadone clinics are one of the most recognizable routes to be medically weaned off of opioids. OpioidTreatment.net found that methadone, a painkiller that blocks pain receptors in the brain and provides relief from the symptoms of opioid withdrawal, reduced the number of deaths associated with opioid dependence and reduced criminal activity related to drug use.

Mangold found success through the clinic, but the negative attitude against medically assisted treatments in the recovering addict community left him feeling isolated.

“I was told by a drugs anonymous program that I wasn’t technically clean because I was on methadone. I felt very turned away. Like here’s a guy that couldn’t go a day without drinking or doing drugs and I was sober,” Mangold said, “I felt no sense of euphoria on methadone and once I got to a high enough dose any dope I used stopped working.”

Sansbury, who works as a recovery coach, has noticed this stigma against addicts participating in medically assisted treatment programs. “You get that a lot [that there’s a stigma],” Sansbury explained. “If you’re exploiting it, I don’t understand why you would fool yourself to say that’s recovery. It’s a fine line.”

Brock Sansbury, a recovery coach and deputy director at the Courage Center in Lexington, South Carolina.

The stigma isn’t isolated to just the recovering addict community. For outsiders who know little about addiction and the science behind detoxification, it’s hard to grasp why an addict would turn to drugs to detoxify. This amplifies the negative stance on medically assisted treatment.

“People thought I was weak-willed, like ‘If only he would just get over that?’” Mangold said.

He lowered his voice in preparation for another quick-witted joke. “It really stinks because I would never look at someone with cancer or diabetes and be like ‘You’re weak-willed! Man-up and kick that diabetes right in the butt.’”

This attitude can be dangerous to recovering addicts many of whom struggle with feelings of guilt and humiliation, he said.

“There’s the stigma that we’re criminals, can’t be trusted,” Mangold explained, “I didn’t want my bosses and parents to know. There was a lot of shame.”

With the methadone clinic, Mangold could partake in the medically assisted treatment without having to tell others. Unlike rehab treatments, he could still attend work, see his family and live life normally.

The method behind methadone clinics relies heavily on a willing patient and attentive doctor. The patient must agree to attend daily doctor’s office visits where they are administered methadone. The beginning dosages can vary but must eventually reach the “maintenance dose” that relieves withdrawal symptoms without producing feelings of euphoria. Patients continue to attend appointments every day until the doctor feels it is time to wean them off of the methadone.

Mangold found that he had to be forceful with his road to recovery. “You have to tell them ‘I want to get off’ because they will keep you on as long as you want to stay on.”

Methadone clinics across the U.S., and even in Columbia, have come under fire for not properly weaning patients off of the painkillers. The fact is methadone can be just as addictive as opioids and when mixed with other drugs or alcohol, just as deadly.

Mangold and supporters of methadone clinics feel it’s the patient’s job to decide they don’t want any more foreign substances in their bodies.

This is a difficult statement for many recovered addicts, especially Sansbury, to get behind. When asked his opinion of medically assisted treatment, the internal struggle in him is noticeable.

“I support medically assisted treatment when it’s used in the right way,” Sansbury said. “I don’t support it when sick people are still taken advantage of by larger entities.”

To Sansbury, who chose to detox naturally, medically assisted withdrawal is walking a fine line.

“It’s like, ‘Oh, the last medicine did you wrong? Here’s this new one, this one will do you right!'” Sansbury said. “It’s basically the same thing, still an opioid.”

Naturally Detoxing on New Carpets

During his lowest point Sansbury recalls living in a maggot-infested house he couldn’t afford with no food to eat, no money besides a jar of coins and only a freezer full of liquor. “I was basically using, abusing, robbing, cheating and stealing, ripping off anyone I could to get the next fix.”

It took months of living in poor conditions, isolated and alone, to finally accept help.

“You 100% have to reach out to somebody,” Sansbury explained. “Getting to that point is the trick. My ego will always tell me, especially as a man, bury it, stuff it, deal with it. Tie your shoes, put your pants on just like any other man, walk out the door, do your thing”

Sansbury shifts in his chair, not able to sit still for a moment.

“Addiction doesn’t discriminate. It will rob you of your soul, of your morals. It will rob you of everything you held dear to you in your life. If you want to get any of those things back you need a catalyst. A nudge, a judge or a grudge.”

It was a nudge, or more precisely, the kicking down of a door by a close friend, that pushed Sansbury to detox naturally. “I just kept telling myself make it one more day, just one more day. It was this very intense methodical battle.”

After detoxing he boarded a flight to Naples, Florida, and attended a 28-day treatment program.

“I remember what the carpets smelled like,” Sansbury said, “It was this thing of new beginnings, new carpet, new life.”

Sansbury’s experience with naturally detoxing saved his life. He recommends this type of program for recovering addicts over medically assisted treatment. He’s seen the dark side of methadone and Suboxone.

“Without any legitimate statistics behind this, personally I’ve seen it be exploited more than it has been successful.”

The Courage Center, a youth drug recovery center located in Lexington, focuses on bringing awareness to the community.

However, Sansbury’s clashing opinion rears its head once more. “I had never heard of medically assisted treatments in 2013,” Sansbury said. “I would enjoy the conversation with myself six years ago ‘If you knew about those things and they were a resource you could’ve used, would you use it?’ I don’t know.”

Road to Recovery

There are a million reasons why it’s not easy to get clean. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, drug overdoses and addiction killed 70,237 people in 2017. Opioids accounted for 47,600 of those deaths.

Declaring opioid addiction an epidemic put big pharmacy companies and drug manufacturers on notice that the era of unbridled opioid distribution is over. Thousands of lawsuits have plagued the companies, calling them to take responsibility for underplaying opioid’s addictive nature and pushing doctors to overprescribe.

“When I was going through this, there wasn’t this hyper-focus on opioids,” Sansbury said. “It was pretty easy to go into the doctor and say ‘I have a hurt shoulder’ and get a prescription.”

The newfound understanding of this epidemic has made it difficult to get opioids and given hope to the future of opioid addiction, but there is a long way to go with helping recovering addicts already affected.

To encourage efforts, the government has continued to pledge funding to combat the opioid crisis. Most recently, the Trump administration granted $1.8 billion in funding meant to expand access to opioid addiction treatments. This gives hope to those searching for detoxification treatments.

The 2002 FDA approval of Suboxone, a mixture of buprenorphine and naloxone, also brought hope to those who found methadone unsuccessful. Unlike methadone, Suboxone’s ceiling limits side effects. The active drug buprenorphine reduces the risk of overdose by approximately 50% according to Harvard University and the inclusion of naloxone curbs opioid cravings. In case of relapse, Suboxone will even block the effects of ingested opioids. All of this, as well as the ability to take it at home, puts Suboxone as most recovering addicts preferred method of medically assisted treatment.

For recovered addicts Mangold and Sansbury, it comes down to the mindset and willingness to change. It’s not just about getting clean, it’s about sustaining the clean.

“The people I used to see I couldn’t hang out with anymore. I was three months clean and they would be calling me asking for dope,” Mangold said, “I think it’s an entire personality change.”

Once their physical withdrawal symptoms subsided, Mangold and Sansbury went through the emotionally taxing process of examining their addiction.

“You’re looking at yourself and seeing your real relationship with drugs and what you have given up for them. Why do you need something so big to help you and what’s going to replace that,” Mangold said.

Mangold, like Sansbury, doesn’t recommend going through this soul examination alone. His advice to recovering addicts is to find support, a 12-step program or recovery community to walk you through.

Now What?

Many recovering addicts find themselves asking “Now what?” Mangold has been clean since Oct. 4, 2008, and Sansbury has been clean since Oct. 16, 2013. Their “Now what’s” are better than they could’ve ever imagined.

“Just finally enjoying life again,” Sansbury said.

Mangold is effusive about his new beginnings.

“When I got clean I was like ‘I hope I can get my life back,’ and I never did, thank God,” Mangold explained. “I have a new and amazing life. I wake myself up every day and I get on my knees and I’m so grateful to my higher power for the life I have now.”