Jens Pierre D’Autel installed solar panels on the roof of his West Columbia home in November. His home system has generated more than 40,000 watts of energy, enough to offset more than 1,000 pounds of carbon dioxide emission.

When Frank Knapp gets the monthly electric bill for his business, he sits down at his desk and does a little happy math.

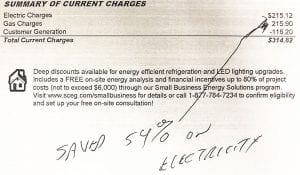

First, he checks out how much SCE&G charged for heating or cooling his Columbia office building. Then he subtracts the dollar amount in solar credits he earned from his rooftop solar installation. In February, his $215.12 bill was decreased by $116.

A quick calculation, and Knapp figured out he saved 54 percent on his power bill for the month.

“Nobody wants to pay more than they have to for energy,” Knapp said. On average, he saves 50 percent per month on his electric bill. In January, he saved 125 percent on electricity.

Knapp, the president and CEO of the S.C. Small Business Chamber of Commerce, is a solar evangelist. Environmental protest signs adorn his walls and photos with Democratic politicians sit in frames.

As CEO of the small business chamber, Knapp works with utilities to put more solar energy on the grid, but it’s an uphill battle.

“There has always been a perverse incentive for utility companies not to encourage energy compensation,” he said. “SCE&G has to be prodded to do it. Duke was prodded to do it.”

Solar energy has been on an upswing since then Gov. Nikki Haley signed a solar bill in 2014.

The bill opened the state to solar energy, bringing in jobs and investments from private companies. It also allowed for solar financing so homeowners could purchase rooftop installations with a loan, in the same way a new car is financed.

Jens Pierre D’Autel installed solar panels on his roof in November. A door-to-door salesman for Utah-based company Sunrun knocked on his girlfriend’s door. D’Autel’s girlfriend wasn’t interested, but he was. By the end of January, he was connected to his co-op’s power grid and began producing energy.

D’Autel, who works in information technology for the University of South Carolina, paid roughly $40,000 for panels on the roof of his West Columbia home through a 20-year loan. Using the federal and state tax credits he has received so far, D’Autel has already paid $6,500 on his loan.

D’Autel can monitor how much energy he is producing with a mobile app connected to his metering box. Since installing about seven weeks ago, his energy intake is roughly equal to planting 40 trees and removing 1,500 pounds of CO2.

Carbon dioxide, or CO2, is a gas emission that is harmful to the environment. Everything from cows, to cars, to our own breaths emit CO2 into the atmosphere. It’s a greenhouse gas, which means it gets trapped in the atmosphere and contributes to heating up the planet. According to the Mother Nature Network, humans release about 30 billions tons of CO2every year.

“It shows me how much the panels are producing,” D’Autel said of the app. “You know, when the clouds roll in it goes down.”

The intermittency of solar energy makes it unreliable. Homeowners with panels have to stay plugged into the power grid. On cloudy days or at night, most homes have to switch back to electricity.

As part of the 2014 energy bill, utility companies are legally required to buy solar energy from homeowners in exchange for electricity during low-producing intervals. Known as net-metering, utilities buy solar energy from homeowners in the form of a credit on their bill. It’s how Knapp saved more than $100 last month.

Currently, an artificial cap is placed on net metering. When utilities reach 2 percent of solar energy in their portfolio, they don’t have to buy the renewable power from homeowners at the competitive rate.

“Once you hit that cap, there is not enough incentive [to install rooftop] because utilities control those rates,” said. Tommy Gardiner, communications director for Conservation Voters of South Carolina.

A bill under debate in the Senate would extend the cap on solar for two more years, protecting the financial incentive to buy solar.

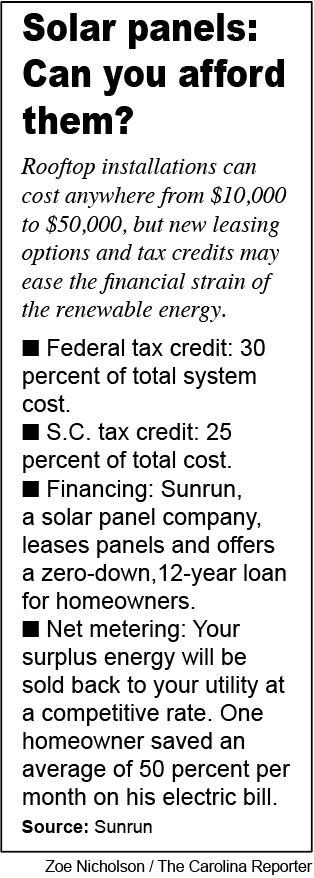

The price of installations is still a roadblock for many people, but advances in the technology, including batteries, are making a fully-solar household a reality.

“Is it worth it? Psh, yeah!” Knapp said.

Frank Knapp is a solar advocate. The president and CEO of the S.C. Small Business Chamber of Commerce works with utility companies trying to make them buy more solar energy for the public grid.

Jens Pierre D’Autel’s mobile app monitors the energy his solar panels generate throughout the day. Even in the winter months, his system generates enough energy to significantly offset his electric bill.

The average solar rooftop installation can cost roughly $40,000. Solar companies have financing options that let homeowners like Jens Pierre D’Autel pay off their panels with a 20-year loan.

Net metering boxes, left, send the surplus solar energy homeowners generate back to the grid. When this surplus occurs, rate payers earn a credit on their electric bills. Frank Knapp has had panels since 2016 and said he saves roughly 50 percent on his bill every month from net metering credits.