John Crangle, Democratic candidate for S.C. House District 75, has spent much of his adult life advocating for reforms in government, giving him a unique perspective on how to make the legislature better serve the people.

John Crangle’s proposal would dissolve the South Carolina House of Representatives, getting rid of what he considers as simply “a stepping stone” to becoming a Senator.

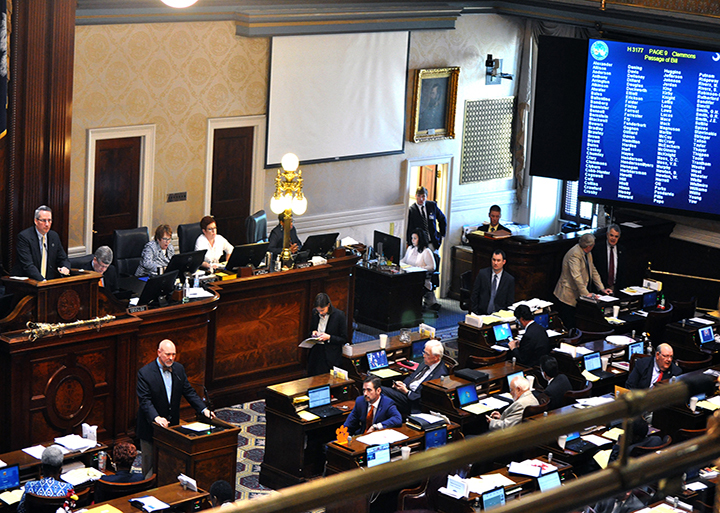

124 members of the South Carolina House of Representatives might not be too keen on the prospect of their jobs being eliminated for a unicameral legislature.

The South Carolina Senate would be full-time under John Crangle’s proposal, meaning the chambers would be empty much less often.

Don Fowler thinks John Crangle’s proposal of a unicameral legislature in South Carolina is interesting, but says that the history in America of a bicameral system points that it is the better way.

John Crangle is a Democrat running for the South Carolina House of Representatives, but he is already planning to wipe out his own legislative chamber if elected.

After spending decades rooting out corruption in the State House, the longtime face of the watchdog organization Common Cause in South Carolina, has seen first-hand what he considers to be incompetence at the highest level.

“I’ve been going over there since 1987 and most legislators don’t know anything about the actual process,” Crangle, 77, said. “Whatever the majority leader tells them to do, that’s what they do.”

Crangle plans to tackle the problem with a radical solution. He wants to abolish the South Carolina House of Representatives and establish a full-time Senate as a unicameral legislature. He believes the House has become a training ground for future senators.

“Quite frankly, the quality of senator on average is higher than in the House,” Crangle said. “It’s kind of like the difference between Double-A baseball and Class A baseball, though in this case it may be more of Double-A to college.”

According to Crangle, combining that inability to perform the job, with what he says is a continued culture of corruption in the State House, results in an inefficient and wasteful legislature.

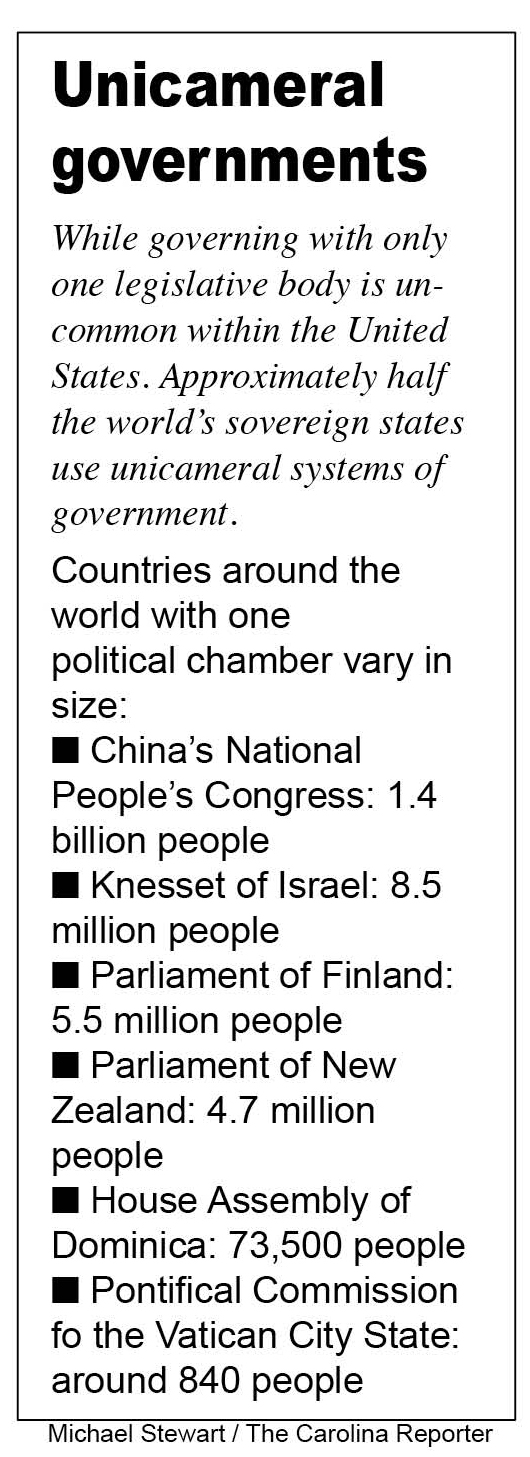

Adopting a unicameral legislature would mean South Carolina. would join Nebraska as the only other state with one legislative body. In 1934, Nebraska approved a constitutional amendment abolishing the House of Representatives and in 1937 “the Unicameral” met for the first time.

Nebraska’s legislature is made up of 49 senators, each chosen by a single-member district or constituency a nonpartisan election. What this means is the top two vote-getters in each primary are entitled to run in the general election, regardless of party affiliation.

John Hibbing, a professor of political science at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, says that Nebraskans, on the whole, are happy with their form of state representation.

“It works pretty well and the differences are maybe less than they would appear to an outsider,” Hibbing said in a telephone interview. “I think if there was a proposal to change back to two-house legislature, it would probably fail.”

The Nebraska Legislature differs slightly from what Crangle hopes to accomplish in South Carolina. Nebraska senators still spend only 60 to 90 days a year in the capital, Lincoln, performing legislative duties, far from the full-time scenario Crangle envisions.

And the different demographics of the two states make it hard to project whether voters would be as pleased as they are in Nebraska.

“There’s a strong populist tradition here,” Hibbing said. “I think Nebraskans are a little bit proud of it, something unique as the only one in the union.”

To get to a one-house general assembly, Crangle will have to navigate the complicated process of amending the South Carolina Constitution. Scott Huffmon, professor of political science at Winthrop University, says that may look easier than it actually is.

“We do have one of the most amended constitutions of all the state constitutions in the United States of America,” Huffmon said. “But that is because we have one of the oldest, still functioning ones. It’s not technically among the easiest to amend.”

Phil Cheney, the only Independent candidate for governor, thinks Crangle’s idea is very interesting but he isn’t completely on board.

“A unicameral legislature sounds like a good idea to me, but I think the Senate was designed to be a part-time job in South Carolina,” Cheney said. “It was for those who were retired or had other sources of income, and I really think we need more retired folks to hold seats.”

Crangle’s reforms don’t stop at just abolishing the House. He’d also limit the influence of money on elections by banning campaign fundraising in non-election years. He says this would reduce a number of conflicts of interest within the legislature.

“It’s like an auction house over there when you have leadership that’s taking money from their own campaigns,” Crangle said. “They’re taking caucus money too. It’s very easy to corrupt from the top down.”

While Crangle’s proposal has precedence in government, there is skepticism that it will get any traction.

“Oh, I don’t think the House is really going to like that very much,” Gov. Jim Hodges, who held office from 1999-2003, said in a phone interview. “Maybe John wants to get the idea out there so people will talk about it.”

Crangle may find that his plan to abolish the House of Representatives has resistance even inside the Democratic Party. Don Fowler, former national chairman of the Democratic National Committee doesn’t think it’s viable.

“I think there is wisdom in having two bodies,” Fowler said. “Every state but Nebraska has two, the U.S. Congress has two and I think the U.S. Constitutional Convention of 1787 was wise in creating a House and Senate with different tenures, different geographical areas and people that they represent.”

Just getting seated in the State House will be a challenge for Crangle. District 75 is solidly Republican, voting in Rep. Kirkman Finlay III, R-Richland, the last three election cycles. Crangle is also severely out-funded by his opponent.

“It’s an uphill struggle for me,” Crangle said. “It’s a gerrymandered, Republican district and I’m going up against a guy who is worth $50 or $60 million, so it’s a David-versus-Goliath situation.”

He’s not interested in mudslinging to get ahead.

“My campaign is not personal attacks,” he said. “I know Kirkman’s mother and I knew his father for years as well. This is strictly about reform ideas that I think have been needed for a long time.”

And his campaign is solely focused on those reform ideas. While he may have an opinion on other issues, Crangle believes the government must be fixed to streamline solutions to other problems.

“I’m not going to talk about distracters, like the Confederate flag or abortion,” Crangle said. “We’re spending $22 million in excess on the House a year, that’s money that could be used to solve things.”

That attitude is unsurprising to many of the people who are familiar with John Crangle’s past work.

“You can use any frank metaphor you want along the lines of an uphill battle to describe this election,” Huffmon said. “My guess is that he views this as a chance to get a broader platform to try and force those in power to acknowledge issues he cares about.”

But Crangle wants it to be clear that he is not running a sideshow campaign. He wants to win, but in order to do that he knows the political climate must be right.

“I think I have a chance because you don’t have a presidential election going on,” he said. “I’m going up in a year where I think the governor’s race is up for grabs more than most years and that will motivate a lot more Democrats to vote. It’s an uphill struggle, but if God’s on your side then it works miracles.”

For Crangle, this election is, hopefully, the culmination of a lifetime of work boring into the deep roots that corruption has taken in politics. He is the author of “Operation Lost Trust: And the Ethics Reform Movement.” It’s a 607-page magnum opus on the 1989 FBI sting operation in the South Carolina General Assembly, that saw multiple legislators indicted for accepting bribes.

After wading through that political dirty laundry and witnessing a similar scandal almost 30 years later, in which almost half a dozen current or former legislators were indicted in a special prosecutor’s investigation, Crangle knows that it’s one of the most difficult tasks to fully accomplish.

“The nature of the corruption has changed,” he said. “Corruption is like bacteria. You can treat it with an antibiotic, but eventually it builds a resistance.”