Sumter farmer Nat Bradford tends to his fields through out the day. Bradford believes hemp can help South Carolina farmers if it is used as a cash crop, and only if farmers are given more control over its production and marketing process.

In 2017, after a near unanimous Senate vote, South Carolina became the 31st state to legalize hemp cultivation.

Nat Bradford’s Sumter farm has a one-acre test plot ready for when hemp is planted. Hemp as a crop is ready to harvest after four months, usually pest-resistant, protects the soil because of its deep roots and can grow up to 15 feet.

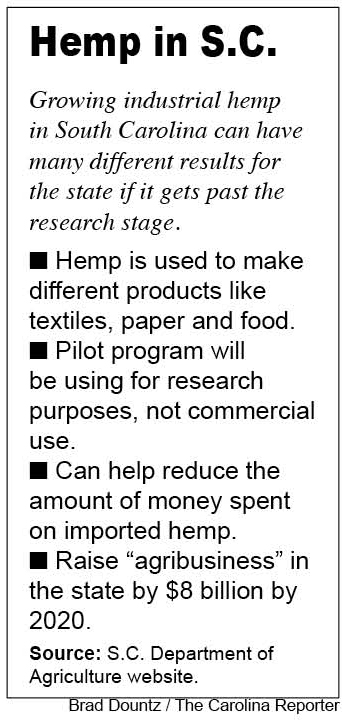

Sally McKay, communications director of the S.C. Department of Agriculture, says industrial hemp production can help rural areas in the state as well as grow South Carolina’s “agribusiness” economic impact by $8 billion by 2020.

A toy tractor in front of Nat Bradford’s house. Bradford hopes one of his children will get the opportunity to work on a real one when they inherit his farm in the future.

Up the dirt road leading to his 10-acre Sumter family farm, Nat Bradford pulled his truck to the side to look over his wide green crop fields. Running around, but still close enough to Bradford, his dogs Brendal, a mixed breed, and Little Bear, a chocolate Lab, scampered. The 42-year-old farmer was getting started on the day and getting prepared to work on a new crop that hasn’t been grown in South Carolina since the 1930s.

Bradford is one of 20 farmers in South Carolina who will be growing hemp as part of the state’s Industrial Hemp Pilot Program. Last May, Gov. Henry McMaster signed the program into law allowing 20 farmers to grow up to 20 acres of hemp each.

The 20 farmers will work with five universities across the state to monitor the results of the crop throughout the year and see if hemp can become a viable industrial product.

“I’ve been interested in hemp since I was in college,” Bradford said. “Actually, I was going to do one of my exit papers on an internship up north on hemp and I finally changed it at the last minute.”

Bradford comes from a long history of farmers. He has already made a name for himself with his watermelons, but it’s hemp that has him talking on a warm Monday morning.

“Most of what we’re going to be doing here is going to be test plots. We’re going to have about six different strains that we’re going to be testing,” Bradford said.

Bradford says he has not received his seeds yet, but hopes to start growing hemp by May. He has a partnership with another farmer to grow a majority of the hemp on 19 acres on his partner’s farm, but he has his one-acre test plot on his own land already measured out. Bradford wants his hemp crops to have a no-till cultivation process; no chemicals and allow polycropping, so multiple species to grow simultaneously.

Bradford will be working with Clemson University, his alma mater, on researching the hemp strains. They plan on concerning themselves with “a broad spectrum in their research.”

“This is an education opportunity and when you don’t have a program, it’s hard to talk about with any purpose, with any relevance,” said Sally McKay, the director of communications at South Carolina Department of Agriculture. “But we have that now and we want to continue to tell the story.”

Hemp as a crop of the future

Hemp comes from the same plant as marijuana, but is cultivated differently in order to extract different products like oil, food, health supplements, clothing, paper and textiles. Bradford has been an advocate for hemp for over two decades, so he knows that hemp can help take the weight off of other industries like timber.

Foresters are having to harvest younger trees so that “we’re not getting the quality lumber out of things,” Bradford said.

“If we could take some of the pressure off of the forestry industry and supplement it with annual crop fiber we might allow our forest to grow longer, have higher quality lumber.”

Since hemp is derived from the cannibis plant, people often view hemp as similar to marijuana, which is extracted from cannibis and used as a recreational drug. But hemp is cultivated differently. Marijuana, a controlled substance, is grown indoors with a focus on flower harvesting, whereas hemp is grown outdoors for its seed and fiber and is a normal cash crop.

The main chemical in cannibis that can get a person high, tetrahydrocannabinol or THC, is reduced to nearly 0.3 percent in hemp compared to the 30-40 percent THC levels you can see in marijuana.

“It is very important to see industrial hemp and marijuana or medical marijuana as separate. They are different products,” McKay said.

With South Carolina a newcomer to the hemp industry, McKay said the farmers needed to look to other states who have already grown hemp as a model of operations.

“We have looked closely at Kentucky’s program and they are much ahead of us. Our legislation, our program is very largely modeled after Kentucky’s,” McKay said.

Lately, there has been a push for hemp to be removed from the list of controlled substances. Sen. Mitch McConnell, R-Kentucky, expressed his desire to see hemp as a cash crop after seeing benefits it has given his home state.

“I just had an opportunity to see some interesting and innovative products, some of which you see here on the table, made with Kentucky-grown hemp,” McConnell said at a gathering while in Frankfort, Kentucky.

McConnell says he will be introducing the Hemp Farm Act of 2018, a bipartisan bill in the Senate that will legalize hemp as a cash crop and have it removed from the controlled substances list.

“I think many of us — the Department of Agriculture, growers — would like to see industrial hemp declassified from that because when it’s sitting right there with that statute with marijuana, that becomes confusing and it becomes a red flag for consumers,” McKay said.

When the bill was signed into law last year, it was unanimously passed in the House and there was only one “no” vote in the Senate. McKay said that it’s a sign that legislators are seeing hemp as a way to efficiently grow the agriculture industry in the state.

“Of course, many of our legislators are from rural counties,” McKay said. “Hemp in particular is an opportunity that gives rural counties a bit of a boost potentially.”

Rethinking agriculture

Bradford stresses that in order for local farmers to benefit from the potential success of hemp, that they personally need to oversee its production and market it themselves so they can maximize their profits.

“Break that dependency. Get to where you’re farming, you’re producing. You’re not dependent on the government to provide for everything and you’re not depending on your broker to determine your prices for everything,” Bradford said.

“I think that’s the first step to get to. I’m hoping hemp is one of those crops that will be a good one for us,” Bradford said.

Farms have fallen on hard times this decade with the rise in production and decline in farmers, which means less money for the farmers still around to take advantage of the demand.

“We’re expecting more out of the same land with less farmers and we don’t want to see prices change. So unless we change our mindset that we’re going to rethink agriculture on some level, I don’t see as being any different down the long haul,” Bradford said.

McKay said that one of the Department of Agriculture’s main goals is “50 by 20.” It wants to raise the total agribusiness economic impact in South Carolina to $50 billion by 2020 from the current total of $42 billion. In 2019, the state plans on more than doubling both the amount of hemp farmers and how many acres they can grow.

Bradford wholeheartedly believes in hemp’s potential, but he stresses the process for farmers needs to change so they can see monetary results.

“I’m optimistic, but again, I don’t think hemp is going to be that magic bullet,” Bradford said. “If we go in with the same mindset with hemp that we do corn, cotton, soybeans and other crops, it’s just going to end up leveling off and being another commodity crop.”

McKay thinks if hemp can bring in more crop diversity to the state, there can also be a functional dynamic between the new and existing production industries. For the Hemp Pilot Program, it’s all about trying out a new venture and seeing where it leads South Carolina.

“We don’t know where hemp is going to go yet,” McKay said. “We hope it’s going to go somewhere great. We’d like for it to become the next great cash crop in South Carolina and we don’t know. So that’s why this pilot program is so important.”

Bradford has five children that range from ages 6-17 and he plans on passing down his farm to them someday. But even with more and more farms being sold off, he believes he will leave a legacy for his children.

“The land that I’m on now is two generations and my kids will be three generations. It’s not as old, but it’s something that I can build upon.”