Lobbyists fill the second floor lobby of the State House while the Legislature is in session. Relationships between legislators and lobbyists, especially when money is involved, is a key focus of the State Ethics Commission.

The State Ethics Commission recently moved into new office space at 201 Executive Center Drive in Columbia. Inside, the staffers are still unpacking and setting up furniture.

John Crangle, the governmental affairs director for the S.C. Progressive Network, is considered one of the top ethics watchdogs in South Carolina.

With just 12 full-time staff positions, the State Ethics Commission is one of the smallest state agencies in South Carolina. This budget cycle, it’s requesting a $363,689 increase and four additional staff positions.

The South Carolina State Ethics Commission, responsible for enforcing ethics laws for more than 24,000 elected officials and candidates, has been without a lawyer since October, a vacancy that could hamper enforcement of ethical conduct laws.

“Having a general counsel is vital,” said Meghan Walker, who became executive director of the commission two weeks ago. With no other lawyers among the 11 staff members left, the commission is essentially unable to process any cases.

Michael Burchstead left the position in November to practice at Collins and Lacy P.C., and the vacancy could remain for as long as two months. The salary at the ethics commission isn’t competitive with private practice or even other state agencies, he said.

The State Ethics Commission ensures that lobbyists and state officeholders follow ethics laws by investigating and prosecuting violations, but it also serves an educational and advisory role.

From legislators to lobbyists, pretty much everyone seems to agree that the commission is underfunded. But almost every South Carolina department could make the same claim — infrastructure, education, health care. With additional money from the state’s general fund uncertain, one legislator is looking to create an alternative source of revenue for the agency.

Sen. William Timmons, R-Greenville, was inspired by a system every state Bar Association uses to raise money for nonprofit work. Lawyers place money they have to temporarily hold for clients into special accounts, and the earned interest goes to the Bar Association.

Timmons wants candidates and elected officials to place their campaign donations into accounts that would earn interest for the ethics commission. It’s a program that hasn’t been tried anywhere else, according to the national Campaign Finance Institute.

“I think it sounds like a terrific idea,” said Greg Adams, University of South Carolina associate professor of law. The trust accounts have been a “massive benefit” around the country, he said, adding that it makes sense to fund services for a specific group by drawing money from that group.

In addition to raising about $100,000 for the Ethics Commission — about 6 percent of its current budget — the bill would make income and expenditures from campaign accounts available to investigators and journalists.

“I could allege that I raised a whole bunch of money and didn’t spend any money and nobody would know unless they looked at my bank records through a subpoena,” Timmons said. Under current law, candidates and elected officials submit their own ethics filings.

The bill has 18 co-sponsors, enough to bring it out of committee and to a vote. Timmons is working with the South Carolina Banking Association to iron out the implementation of the interest-on-campaign accounts.

The timing for a renewed dedication to ethics couldn’t be better, according to John Crangle, the S.C. Progressive Network governmental relations director. South Carolinians are upset about the SCANA scandal, and legislators are campaigning on bringing ethics and order to state politics.

“Now we have a younger crop of legislators, like Bill Timmons, and I think they’re going to be much more aggressive about reform,” Crangle said.

While the increase from Timmon’s bill would be less than the increase requested by the commission, it would still allow for some much needed changes such as upgraded software and new personnel, according to Crangle.

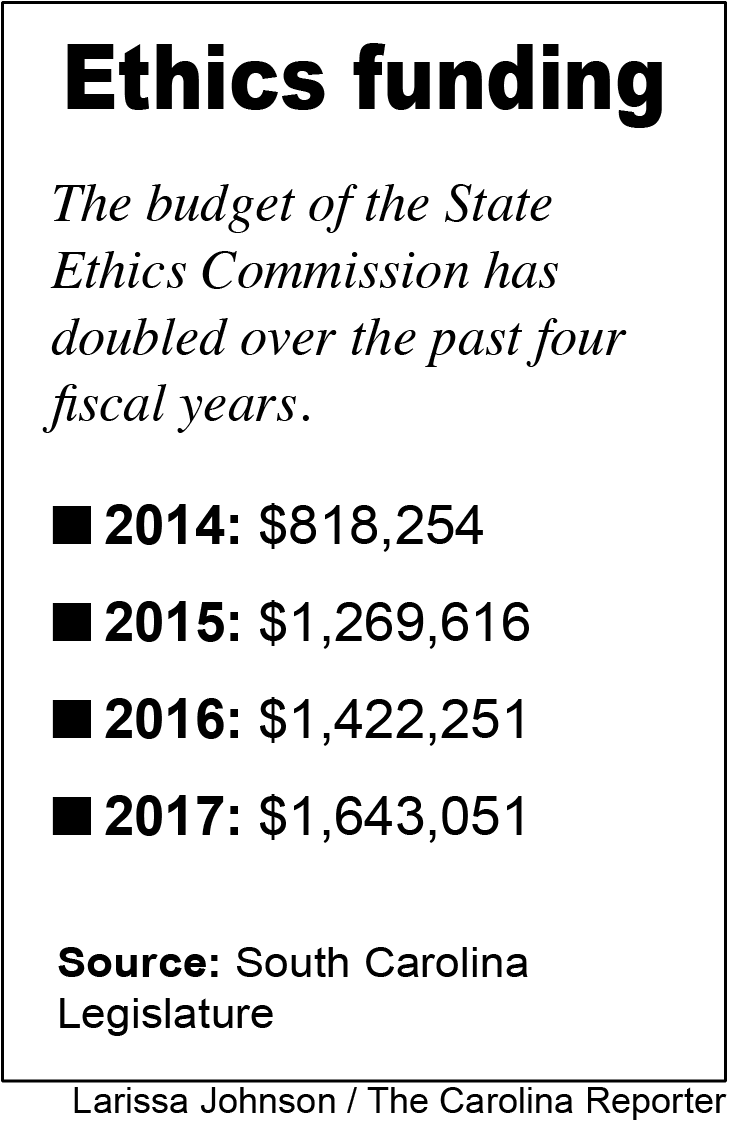

The commission received $1,643,051 from the state general fund for the current fiscal year, and has requested an additional $364,689 for next year. That would be a 22 percent increase, while Gov. Henry McMaster has asked every agency to cut budgets by 3 percent.

The commission is requesting money to add four additional positions to the 15 it currently has, including an investigator and paralegal.

When Burchstead came into the commission in 2015, there was only one full-time investigator. Now, there are four.

“For a number of years, it got so bad that they had to rely on fines and fees and penalties just to pay salaries,” he said. “While the money could certainly be better, as of 2015 or so they’re not doing that any more.”

As the House Ways and Means Committee considers agency requests for funding and prepares the first draft of the 2018-2019 budget, likely to be presented in early March, the Ethics Commission is settling into new, larger offices to accommodate additional staff.

“When an agency like ours isn’t fully funded, like any other government agency, you try to do as much as you can with the resources that you have,” Walker said.

While Timmon’s bill is the only that would create revenue for the commission, others in both the S.C. House and Senate would introduce additional powers and access to information.

“There’s low public trust everywhere,” Timmons said. “We’ve got to make sure that citizens in this country have trust in their public institutions.”