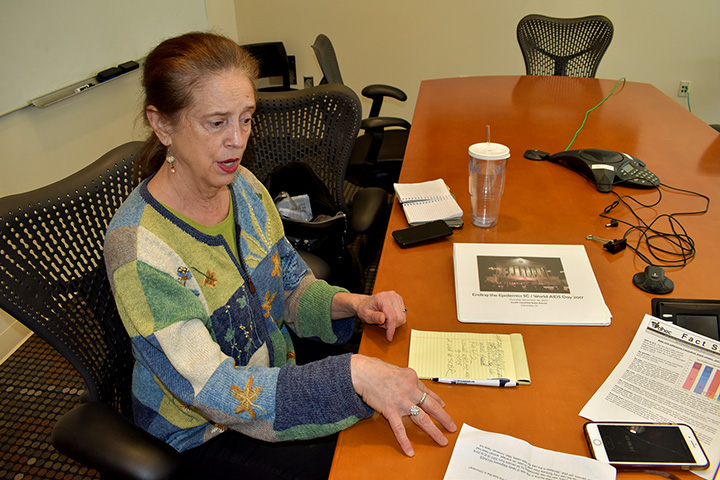

Elizabeth McLendon has been fighting to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic since its inception in the 1980s. She works with the South Carolina Deptartment of Health and Environmental Control as a community advocate to raise awareness about routine testing in Columbia.

President Trump on Tuesday called for an end to the HIV/AIDS epidemic by 2030, a declaration that stunned South Carolina advocates who have been battling the disease and its stigma for decades.

“The fact that he even mentioned the words ‘HIV’ and ‘AIDS’ is significant to me,” said Bambi Gaddist, executive director of the SC HIV/AIDS Council.

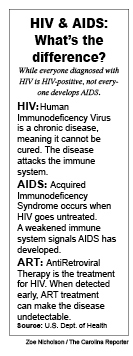

HIV, or Human Immunodeficiency Virus, is a sexually transmitted infection. First detected in Los Angeles in 1981, the final stage of HIV infection is Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, or AIDS. Prevalent among the homosexual and black communities, the AIDS crisis killed more than 700,000 people during the 1980s and 1990s.

Elizabeth McLendon spent the majority of the AIDS crisis in San Francisco, an epicenter for the disease.

“I lost so many people to the AIDS epidemic, it was over 200,” McLendon said. “And I didn’t stop losing people, I just stopped counting.”

Now, McLendon works as a consultant to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Columbia, which has the sixth highest incidence rate of any city in America, according to the S.C. Department of Health and Environmental Control.

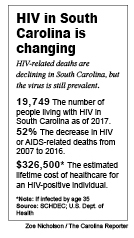

Nearly 20,000 people in South Carolina are HIV-positive, with the majority of those patients African-Americans, according to DHEC. In South Carolina, nearly 24 percent of African Americans live below the poverty level, a factor Gaddist said is connected to the high number of HIV/AIDs cases.

“It [the epidemic] has been brewing for some time now, for decades,” Gaddist said.

One of the major challenges Gaddist has faced in her long fight to end HIV/AIDs in South Carolina is funding. Most federal funding is funneled to larger, “more critical” metropolitan areas.

“While we were addressing urban settings, we neglected the fact that people travel from rural areas to urban settings and then they go back home,” Gaddist said of the lesser-known “rural epidemic” affecting Southern states like South Carolina.

But, Gaddist added, “in order to deal with any issue, you have to acknowledge its existence.”

Which is why the city of Columbia is set to join an international initiative to raise awareness, prevent new diagnoses, promote regular testing and educate the public in cities across the globe. The program, known as Fast-Track City, began in Paris on World AIDS Day in 2014.

McLendon said the program will get “non-traditional players,” like the media and the business community, involved in ending the HIV epidemic, as well as the sexually transmitted infection and viral hepatitis epidemics, in Columbia.

Mayor Steve Benjamin is expected to make the announcement and sign the pledge at City Hall Thursday at 6 p.m.

A possible answer to Gaddist’s call to “acknowledge that we have a problem in this state,” the initiative will work to diminish prejudices associated with individuals who are infected with the disease.

HIV and AIDS stigmas run rampant in the South, especially for states situated along the Bible Belt.

“When you have a cancer walk, everybody comes out and walks for cancer. But when you have an AIDs walk, you have to beg people to come out,” Gaddist said.

McLendon and Gaddist both said the stigmas surrounding HIV/AIDs have not gotten better since the AIDs crisis.

“The dilemma that people like me are in is that people – because of stigma – don’t believe that the people we serve are worthy, they feel some people deserve what they got,” Gaddist said.

Gaddist said Trump’s call to eradicate HIV in his State of the Union is laudable but not feasible without substantial funding. According to the New York Times, the White House said it would provide funds, but did not specify how much.

The cost of HIV treatment over a lifetime is high, especially in a state with inadequate Medicaid services and a high poverty rate. According to a 2015 U.S. Dept. of Health report, a person diagnosed as HIV-positive by age 35 will spend an estimated $326,500 over their lifetime on healthcare.

However, she praised the President for doing something many will not: acknowledging there is an epidemic.

“I call on the community to do what the president did,” Gaddist said.