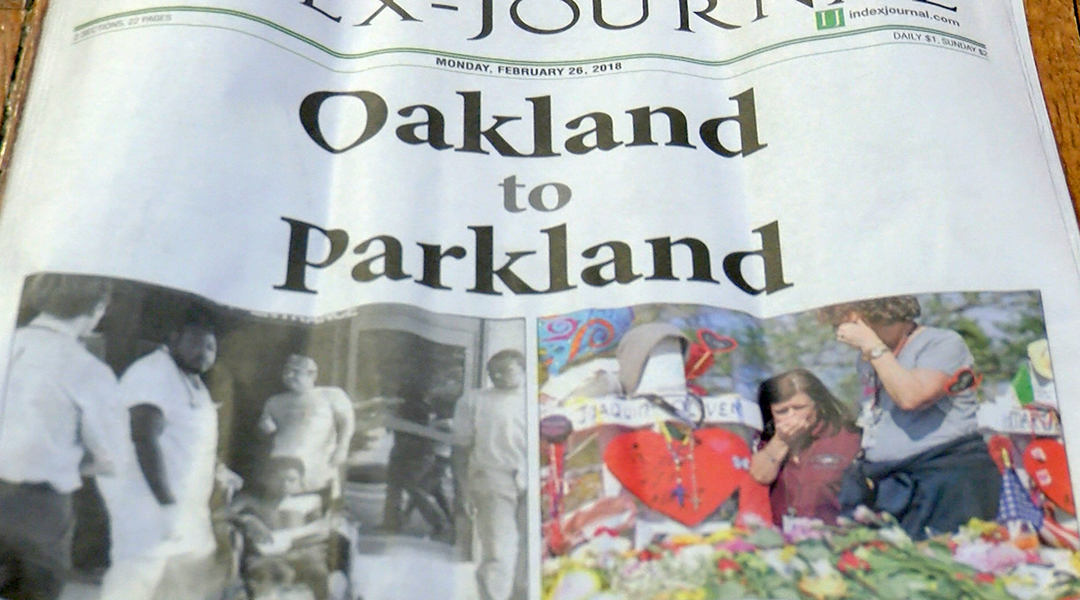

Editors at Greenwood’s paper, The Index-Journal, compare the recent school shooting in Parkland, Florida to their community’s tragedy 30 years ago. The paper’s front page op-ed calls for action regarding gun laws.

A statue marks the memorial for Shequila Bradley and Tequila Thomas. The statue and plaques sit behind the school, which is now named Eleanor S. Rice Elementary School.

Residents of Greenwood, South Carolina, will never forget the shooting that changed their town–even if the rest of the world has moved on.

Jim Coursey spent six years as Greenwood’s police chief. He still dreams about September 26, 1988.

GREENWOOD — Ellie Hodge smiled at the shooter as he walked in.

The first-grade teacher sat across from one of her students, keeping a watchful eye on the bustling cafeteria. A hundred students sat at their tables, eating their lunches that September afternoon in 1988.

“I thought he was a parent,” Hodge said, still incredulous years later at her naivete.”A young parent, but I was new.”

It was her sixth week at Oakland Elementary School. She didn’t know all the parents yet. So, she smiled.

That’s when 19-year-old James William Wilson Jr. opened fire.

Hodge doesn’t remember the gun; she only remembers being shot. The bullet entered the side of her hand. The student across the table looked at her, wide-eyed. Hodge, confused, thought the little boy had thrown a ketchup packet at her.

Back then, the term “school shooting” didn’t exist. It was unimaginable, which is why it took Hodge a moment to realize the situation.

Then she started to scream for students to run.

Lashonda Burt sat further down Hodge’s table when the chaos began. The 7-year-old was shot and immediately blacked out. When she came to, she searched for her teacher.

“I remember Miss Hodge waving at me to come to her,” Burt-Reeder, now married and still living in Greenwood, said. “She was actually shot again in that moment.”

The second bullet entered Hodge’s right shoulder and lodged in her left, bypassing her spine by millimeters.

A cafeteria employee pulled Hodge, Lashonda, and another student into a cafeteria freezer. Hodge told the children to run. Lashonda fled out a side door with other kids, not realizing she had been shot until someone saw the blood on her clothing.

“When I looked down at my arm and my shirt, I saw all the blood,” she said, recalling the moments before she passed out again.

Inside the building, Wilson reloaded the handgun – a nine-shot .22 caliber revolver he stole from his grandparents – in a bathroom down the hall from the cafeteria.

He soon moved to a third-grade classroom and began shooting, killing eight-year old Shequila Bradley and injuring six others, including Tequila Thomas.

Tequila would never regain consciousness.

Shots, then panic

Across town, Chief Jim Coursey sat in his office at the Greenwood Police Department. The scanner crackled as he spoke with a SLED agent. The chief’s ears perked up.

“I remember telling him, ‘I got to go, there’s been a shooting at one of my schools,” Coursey said.

Maj. Urban Mitchell heard the same call in his car as he drove around town. He arrived within seconds on the school grounds, which had filled with dozens of cars and frantic parents.

Three decades later, Maj. Mitchell marvels at how quickly ordinary people arrived at the scene.

“Believe it or not, word had still gotten out, and there were parents arriving just immediately after I got there,” he said.

Mitchell rushed around the back of the school where he found another investigator holding Wilson at gunpoint. The officer had captured the shooter after he climbed out a bathroom window. The police chief drove up as the two took Wilson into custody.

Both describe the scene as chaotic; sheriff’s deputies and SLED agents rushing in, teachers and children bleeding, parents screaming for answers.

Telephone calls heightened the madness; parents who didn’t make it to the scene frantically called the school. A secretary from SLED, along with Coursey’s personal assistant, came to Oakland Elementary and helped answer the calls.

“To hear that panic,” Mitchell said, trailing off in thought. He then summed it up in one word: “Unbelievable.”

A close-knit community that still remembers

The names of Shequila Bradley and Tequila Thomas are etched into granite markers in a small memorial garden behind the school, which now bears the name Eleanor S. Rice Elementary in honor of the principal who guided the school out of the tragedy.

The town renamed the school in her honor after she died in 2010. A plaque outside the school’s front office describes Rice’s leadership in the shooting’s aftermath as “heroic.” Coursey doesn’t know what the town would have done without her guidance.

September 26, 2018, will mark 30 years since Wilson opened fire and took Shequila and Tequila from this world. Wilson had no ties to Oakland Elementary. He lived with his grandparents, and relatives described him as a “hyper-recluse” to The State newspaper. He is incarcerated on death row at Kirkland Correctional Institution in Columbia.

In those three decades, not much has changed about the city of Greenwood. It currently has 23,222 residents and counting, with major chains and stores in its center, up from its 21,613 population in 1980. Tiny shops line Main Street in an renovated arts and culture district now known as Uptown Greenwood. Their owners remember customers’ names, their food orders and family ties.

“It’s a close-knit community,” Mitchell said.

It’s a community that still remembers the two youngsters who lost their lives and those who still carry psychic wounds from that day.

One Greenwood business owner teared up as he talked about Kat Finkbeiner, the physical education teacher who confronted Wilson as he reloaded in the bathroom. When she tried to stop him, he shot her in the mouth and hand.

Finkbeiner survived and was hailed as a hero.

Even three decades later, those who witnessed the aftermath of the shooting continue to live with the effects.

“This was a bad day,” Coursey said. He took a moment to collect himself before he admitted, “I still dream about it.”

Coursey, now retired after six years on the force, calls himself “a big Second Amendment person,” but he isn’t blind to the issue of guns in American society.

“What’s happening now…we’ve got to make some changes,” he said.

Hodge said she struggles to listen to news about the recent school shooting in Parkland, Florida that claimed the lives of 17 students. She has physical reminders: her left hand that fails to make a closed fist, and her PTSD that overrides her senses from time to time.

For the most part, however, Hodge can remember the tragedy without issue.

“It helps to talk about it,” she said.

Burt-Reeder flinches every time there is a call from her children’s school in the middle of the day. Her shoulder aches from time to time, but she views it as a reminder; if she hadn’t been eating at the time of the shot, the bullet would have gone through her neck.

Emotions run high whenever another school shooting leads the national news. There is a sense of being forgotten, the name of Oakland Elementary School lost in the modern wave of school shooting tragedies.

Even if the rest of the world forgets, Greenwood can’t.

“I forgive him for it, but I will never forget that he did that to me,” Burt-Reeder said.