Russell and the best friends he made at Transitions homeless center, Jim, left, and John, far right, used to come to this gazebo at Elmwood Roy Lynch Park, Columbia frequently to paint while at Transitions together. (Photos by Noah Watson)

Carrying a few articles of clothing and some paintings he and his wife created together, Russell boarded a Greyhound bus in Charleston with a one-way ticket to Columbia. It was February of 2020.

In the time since, his journey has included homelessness, grief, illness, art — and a renewed belief in his future.

“I had a pretty normal life,” Russell said. “When my wife got killed, I went ape-shit.”

In Columbia, Russell knew he would be entering the world of the homeless — joining the 700-something unhoused people in Richland County, according to a 2020 report from the S.C. Interagency Council on Homelessness. Richland County has the largest number of homeless of any county in the state.

Before stepping on the bus, Russell lived with his family and worked as a carpenter in Charleston, building custom kitchens. He said almost every second-story home on Broad Street downtown has his work in it. He was most proud, however, of his own house.

“All the furniture in the place I custom-built for my wife,” he said. “From the bedrooms to the dressers to the couch and the chairs. … She actually made the (couch) cushions herself.”

Along with handmade furniture, the wall decor in his home was also handmade. Russell and his wife used to paint together. He said they decorated their walls with the paintings they made, and any paintings that didn’t make it onto the wall went into a binder so they could preserve the work they did together.

When they would paint, they’d sign the painting with a joint signature to denote it was made by the two of them.

“It stands for Jen and Russ,” he said. “We painted together a lot, and she would always make a ‘J,’ and I’d finish an ‘R’ on the side of it. That was the world back then.”

He still uses that signature today.

He and his wife lived with their daughter, who had recently had a child. One day in 2019, his wife went out to get supplies for their granddaughter.

She got into an accident and never made it home.

“It was the day before Thanksgiving,” Russell said. “She had just gone to the corner store to get diapers. … Then the state police came to my door four hours later.”

Three months after that, he lost his job.

“I didn’t know how to grieve,” Russell said. “I almost drove myself nuts.”

Jobless, wifeless and at his wit’s end, Russell decided to leave Charleston — and the responsibilities of his life.

“I spent a whole life doing something, and at the end, it was all gone,” he said. “I was like, ‘Wait a minute, back up, take another look, … Let’s make it a little simpler this time.’”

So he packed his backpack with the aforementioned clothes and paintings, hopped on the bus, and headed to Columbia.

His first night in the city, he slept on the streets. His second night, he slept at Oliver Gospel Mission, a downtown shelter for men. On the third day, he entered Transitions homeless center. He said he found the shelter by following others with backpacks, like the one he had just packed.

Adjusting to homelessness was difficult, said Russell, who prefers to use only his first name. He struggled with the grief of his wife’s passing. Trust issues and a distaste for strangers closed him off from others. It didn’t help that the people he left in Charleston were making what he said were hollow attempts to reach out.

“It was that barrage of questions,” he said. “‘Are you OK? Is everything alright?’ You’d be surprised how many people ask you that, knowing that it’s not.”

Ultimately, he would have two different stays at Transitions between 2020 and 2022. His first stint was nine months.

Cheyenne Gifford, a case manager at Transitions, remembers when Russell came in.

“He was a little closed off,” Gifford said. “He’s in his own self. It’s hard for him to open up.”

Until a Transitions employee broke through.

Catherine Beltran was an art teacher before working at Transitions, and she helped run the art program there. One day, she went to the art room and saw Russell sitting alone, painting. She walked over and sat next to him.

“We were sitting there, not really saying much,” Beltran said. “I was doodling. He was painting. I don’t even remember him looking up at me, and he just started talking.”

Russell said he hadn’t talked to anyone for three weeks until talking with Gifford, and he told her everything.

“She knew my whole life story from the time I was born till that point,” Russell said.

“It felt like hours — it was maybe 45 minutes,” Beltran said. “At one point, he set down the paintbrush and looked up at me. He was like, ‘I haven’t told anybody that since I got here.’”

Beltran said from that moment, Russell changed for the better. Art became a type of therapy for him.

“If I’m angry or have any type of anxiety going on, I start painting and it just goes away,” he said. “Out of my brain and onto the canvas.”

He painted a lot at the shelter, and through the relationship he formed with Beltran, he and two friends he made at the shelter, John and Jim, were granted 24/7 access to the art room when everyone else could only spend an hour a day there.

“I don’t want to say we could get away with murder, but we were doing a lot of things that a lot of people couldn’t,” Russell said.

Sometimes, they’d lock the doors and turn the art room into their own private studio. Russell said if anyone asked them to use the art room when they were there, they’d send them to Beltran for permission, knowing she wouldn’t grant it.

“We’d be like, ‘Oh, it’s easy. All you gotta do is get permission from Catherine,’” Russell said. “Catherine knew that if we sent somebody to her, we didn’t want them there.”

“We owned that place,” Jim said, chiming in.

The trio spent a lot of time together. And they earned the nickname “Duck Dynasty,” after the TV characters, because they all had long beards.

“We’re family,” Russell said. “These are my brothers.”

After his initiation into the shelter, he got a temporary job on the construction team that built the Vista Lofts apartment building on Gervais Street.

For almost seven months while working on that project, Russell was out of the homeless shelter, staying in the Super 8 motel on Forest Drive. He said he paid $70 a night.

“It’s an expensive way to live,” Russell said. “But I was making $200 a day at that point. I didn’t really care.”

But in June of 2021, he was put out of work when he developed a bad case of shingles, a viral infection that can leave painful rashes and sores on the skin. He checked back in to Transitions for 30 days to recover. But by the time he healed, he said, the construction company had replaced him. Jobless again, he was also homeless again.

“I restarted once — I can do it again,” Russell said he told himself.

When the 30 days were up, he wanted to be on his own again. But he was on the streets for a few days before finding his way back to Transitions a third time. This stint lasted six months.

He found another job through a temp agency — working for Manchester Farms at its quail processing plant in Hopkins.

“He was part of our team even though his payroll came from the temp agency,” said Brittney Miller, owner of the company. “He would show up every day and was a wonderful person to work with.”

One day in March of this year, he was asked not to report to the plant but to a house next door. Russell would spend the next few Fridays painting the interior of the house, which would become the place where he lives to this day.

“I had no idea I was ever going to live there,” Russell said. But after a few Fridays of painting, he got the offer to move in and live there. The house, it turns out, is owned by Manchester Farms.

Miller said the house has been in her family for almost 30 years.

“We always try and allow an employee to live there,” Miller said. “Russell and his roommate were so happy to hear that they were the ones that were going to be able to get the house.”

Well, not at first.

Russell was hesitant. He didn’t like the location, out in the country next to the processing plant. More importantly, he hated how boring the white walls were.

“So I go in the kitchen and I find this little bitty thing of dark green paint,” Russell said. “I pour it into the white paint and mix it myself, and I painted the kitchen green. I was like, ‘OK, I can live with this now.’”

When it was time to move in, Miller knew Russell and his roommate didn’t have the money to furnish the home. She and some of the other company employees took care of that, buying them mattresses and frames, living room furniture, tables and kitchen supplies such as pots and pans.

His roommate is someone he met at Transitions.

“As long as they’re happy and they want to stay, … it’s theirs for however long,” Miller said.

“However long” for Russell is four years and three months. That’s when he plans to retire and travel the world, a trip he planned to share with his wife.

“The one thing I wanted was for me to retire, and for her and I to be able to just travel the world,” he said. “The dream is still exactly the same, just minus somebody. I’m going to do it for both of us.”

Russell and his late wife used to paint together before she died. He has a binder preserving the art she made and that they made together.

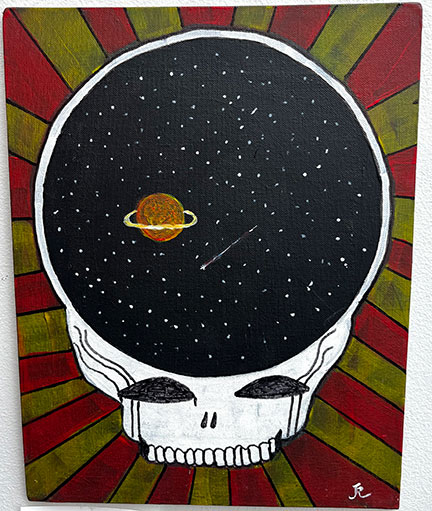

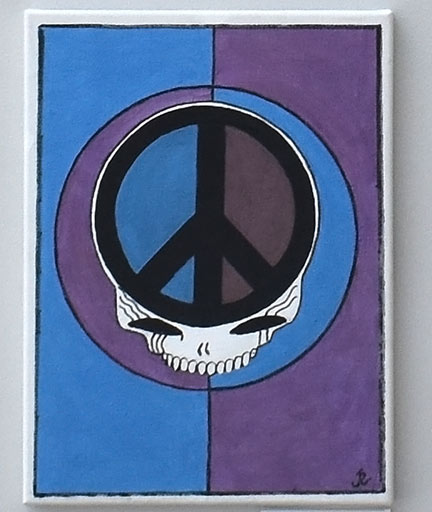

Russell is a big fan of the Grateful Dead band. He paints the band’s famous “Dancing Bears” logo frequently. He followed the Grateful Dead on every stop of its 1977 tour, selling grilled cheese sandwiches in the parking lot to fund the trip

Russell lived in a motel for two months before moving into his house. Now that he has moved in, he loves spending time sitting on his front porch.

Russell painted the front view of his house for a recent art exhibition at the Columbia Metropolitan Airport.