Meredith Berry sits on the porch of her home. Berry said she was hospitalized with West Nile virus symptoms for a week. Photo by: Caity Pitvorec

Richland County residents have grown more concerned about West Nile virus as cases rise.

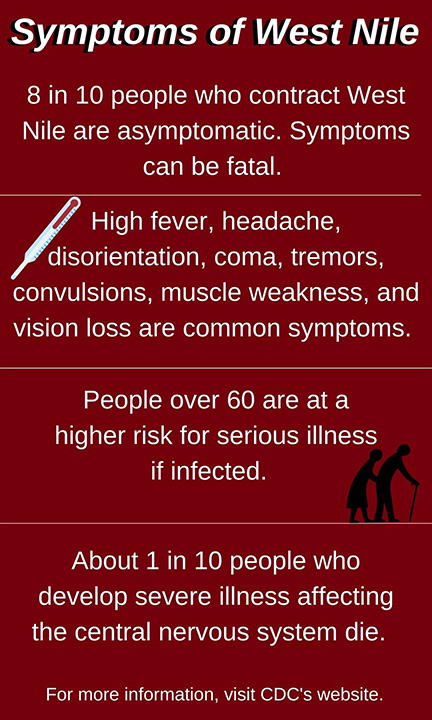

People contract the virus when bitten by a mosquito typically infected by a bird. After a 2- to 14-day incubation period, people may develop symptoms such as a headache, body aches, confusion or worse.

Meredith Berry is an active, healthy, 71-year-old who spent a week in the hospital after being bitten by a mosquito.

“It’s really serious,” said Berry, who lives near the University of South Carolina. “I could have easily died.”

After being released from the hospital, Berry sent an email to her neighbors warning them of the virus and ways to stay safe:

“Please put on mosquito repellant at all times when you’re outside – I didn’t, and was one of the unlucky ones,” Berry’s email said. “Don’t be like me!”

Berry started experiencing symptoms Aug. 29 while walking her doberman. She described the symptoms as coming in waves: first came fatigue, then a headache, and after she laid down, she was seeing double.

“(The virus) was taking over – (that) is what it was doing,” Berry said. She described her headache as pressure closing in on her brain. Berry is still recovering but said she is grateful to be OK.

The South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control said Sept. 12 that one Richland County resident had died from the virus and six other cases were confirmed in the county. Berry was one of the infected.

Though DHEC reports that more than 70 percent of West Nile cases are asymptomatic and chances of a serious reaction are low, there is still a possibility of developing encephalitis, a potentially fatal inflammation of the brain.

“If we have 129,000 people in the major metropolitan area and 10,000 of them are exposed to it, then that’s a problem because just simple math tells you some people are going to develop this severe – severe form of the illness,” said Richard Blackmon Jr., the chief code enforcement officer of Columbia.

Even though a small percentage of the population may develop the illness, he said, people should still be concerned and take precautions.

“You don’t want to be the one in 10,000 or whatever that develops the illness,” Blackmon said.

Dr. Eric Brenner, an epidemiologist and USC professor, warns people with the same logic as Blackmon’s.

“How many students are there at USC? 20,000 or 30,000,” Brenner said. “So even if something that’s rare, that happens to one student in a thousand, if you have 20,000 students, that could be 20 students who might get sick.”

After learning about West Nile, Zack James, who works at the Center for Integrative and Experiential Learning at USC, said he is taking extra measures to be safe.

He uses “sunscreen every time I go out,” James said. “But now I’m trying to layer on bug spray, too, as a just-in-case thing.”

James and his partner often work in their garden, where mosquitoes are abundant. Wearing bug spray is a simple step to prevent bug bites.

“I’m not super worried about West Nile, but it’s an easy precaution to take,” James said.

DHEC and the federal CDC both recommend using insect repellents that contain active ingredients such as DEET to prevent mosquito bites.

“The only thing that will stop (mosquitoes) from biting you is wearing bug spray,” Blackmon said.

The code enforcement office in Columbia is spraying adulticide, a chemical that kills adult mosquitoes, as many nights as possible in affected neighborhoods, Blackmon said. He said spraying is being done from midnight to 4 a.m. and will continue until there are no more positive mosquito pools..

Photo of a mosquito on a human. (Courtesy of CDC)

Infographic describing the symptoms of West Nile virus if serious illness develops. Graphic by: Caity Pitvorec

Photo of adulticide chemical Columbia Code Enforcement Division uses to kill adult mosquitoes. Spraying is from midnight to 4 a.m. Photo by: Caity Pitvorec