A fully restored B-25 WWII bomber used for Doolittle Raid flight training sits between two smaller aircraft at downtown Columbia’s Jim Hamilton-L.B. Owens Field. (Photo by Sammy Sobich)

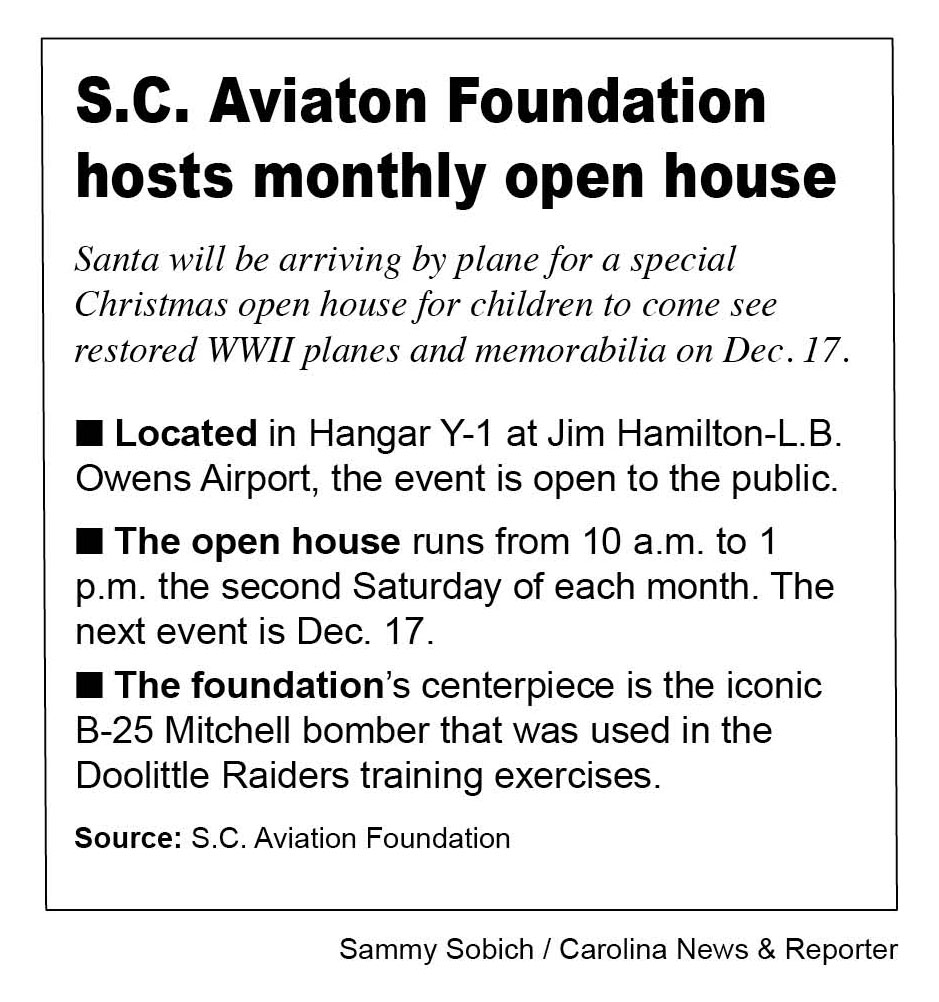

A group of volunteers is working to build a museum around a restored B-25 recovered from a South Carolina lake after the plane went down during a WWII training exercise that has its roots in Columbia. The B-25 Mitchell bomber that appears “flight ready” will help honor one of the most successful air raids in American history — the Doolittle Raid.

Also known as the “Tokyo Raid,” the secret attack was the first good news Americans had heard from the Pacific Theater almost five months after Imperial Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

The raid left 87 Japanese dead and 462 injured. And while damage to Japanese military and industrial targets was slight, the raid had major psychological effects. For the United States, it raised morale. In Japan, it raised fear and doubt about the military’s ability to defend the island country, according to James Scott’s book “Target Tokyo.”

President Franklin D. Roosevelt wanted to strike back after the devastation of Pearl Harbor. He needed a great leader to command the attack on Tokyo. He found him in the legendary, charismatic stunt pilot James “Jimmy” H. Doolittle of California.

In the 1940s, aircraft racing was the boldest undertaking of the time, according to Ken Berry, president of the S.C. Historic Aviation Foundation, one of the groups involved in the museum project. Doolittle was one of the most iconic stunt pilots of the era, accomplishing feats no other pilot had and wowing crowds at air shows around the country.

Doolittle traveled to Columbia Army Air Base in 1942, under Roosevelt’s instruction, to round up volunteers for the secret mission. In February of that year, 16 flight crews — 80 men — were assembled for what would become the “Doolittle Raiders.”

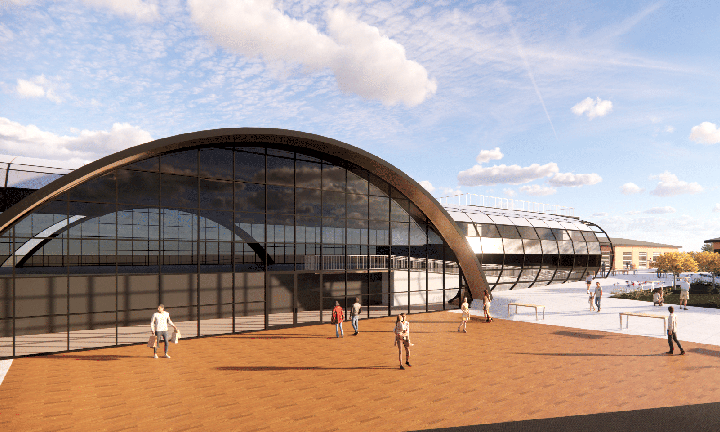

Air Force veteran and a founder of the Columbia-based American Heritage Foundation Gay Suber is heading the project to raise funds to build a brick-and-mortar museum at the Columbia Metropolitan Airport. The site is a 5-acre plot the foundation owns adjacent to the airport. The group is in the early design phase with JHS Architecture, with hopes of breaking ground in the next few years.

The S.C. Historic Aviation Foundation, which owns several restored war-time planes at Owens Field, will provide them and other memorabilia for the museum.

In 1942, Army Air Corps pilots who were already in general training in Columbia volunteered to join the covert mission. Once the group was officially created, Doolittle’s crews and planes moved to Florida for training, according to the Naval History and Heritage Command.

The U.S. War Department had acquired the facility, formerly known as the Lexington County Airport, in 1941 and expanded it to serve the war effort. Runways, hangars, roads and buildings were added during the war.

Suber had a first-hand look at what went into turning the airport into a war-time training center.

Suber’s father, John Robert, did the clearing, grading and drainage work for what would soon be known as the Columbia Army Air Base. C.G. Fuller, a contractor from Barnwell, paved the runways, taxiways and the roads.

The pre-war work finished in the late summer of 1941.

Suber said the young men’s reaction to being recruited was impressive.

Those who volunteered for Doolittle’s mission weren’t told what they would be doing.

“Everyone in the room immediately stood up and volunteered even though they knew nothing (of the mission and knew) they might not come back,” Suber said. “It was just the mentality of the time.”

Crews practiced intensive cross-country flying, night flying and navigation, as well as low altitude approaches to targets.

They were told it was a one-way mission, as there would not be enough fuel in the lightened planes to make the return trip.

The B-25 bombers planned a risky maneuver — launching from the deck of an aircraft carrier, something that had never been done. They took off from the short runway of the USS Hornet in the Pacific Ocean, at a point just east of Tokyo. The goal was to fly over Japan, drop bombs, and land at airbases in China.

Hours before they were set to launch, they spotted an armed Japanese boat and sank it. Doolittle feared the Japanese crew had radioed a warning back to headquarters. So he launched the raid early, even though his planes might not have enough fuel to reach landing fields in friendly Chinese territory after the bombing.

Nine men did not make it home. Three were killed attempting to land in China. Eight were captured by the Japanese, and three subsequently executed. A fourth starved to death, and the four others were held captive until the end of the war.

Other airmen were taken in by friendly Chinese villagers. One plane landed in Russia and the crew was held captive.

Suber remembers the effect the war had on him, even as a 4-year-old. He remembers going to the grocery store with his mother and overhearing casual conversations of war stories.

Thomas J. Smith IV is a senior architect for the museum. His grandparents were in the military during WWII, so he said he has a “feeling of responsibility” to assist with the project.

The museum’s floor will be a concrete slab that served as the original floor of the air base’s quartermaster building.

“We’re designing it so that the glass wall along the front can be opened up and the B-25 can be rolled into the space and sit on the concrete floor of the museum,” Smith said.

The 20,000-square foot slab has old railroad spurs where supplies and equipment were unloaded from rail cars. Smith calls them “artifacts” of the building structure.

Another historic element of the property is a brick wall from one of the original buildings that stands on the west side of the site. JHS plans to incorporate the wall into the museum’s exterior, after reinforcing it with steel elements and shoring up the mortar joints.

Along with the foundations, a nonprofit group called the Children of the Doolittle Raiders, will help provide wartime relics.

The president of the organization since 2015, Jeff Thatcher of Arkansas, is especially close to the project. His father was gunner and engineer Cpl. David J. Thatcher of Montana. His No. 7 plane, The Ruptured Duck, crash-landed off the coast of China after bombing Tokyo.

Thatcher went through most of his childhood without his father really opening up about his wartime experiences.

“I was well into my elementary school years before I knew anything about the Doolittle Raid,” Thatcher said.

“My father was 20 years old at the time, one of the four youngest flyers on the raid.”

Before he passed away, David Thatcher told his son “he was just doing the job” he was trained to do.

The survivors met each year at a reunion, choosing different locations around the country.

In 2002, for their 60th reunion, the 13 surviving members chose Columbia and were honored with a parade down Main Street and several opportunities to meet the public.

The Raiders were praised for being many things, including humble.

The last surviving Raider, Richard “Dick” Cole of Ohio, died in 2019 at the age of 103.

Design concept for the Doolittle Raiders & Columbia Army Airbase Museum at the Columbia Metropolitan Airport (Rendering courtesy of JHS Architecture)

A B-25C Mitchell bomber in training above Columbia (Photo courtesy of William A. Hamson)

B-25C aircraft training above Columbia (Photo courtesy of William A. Hamson)

Armorer loading bombs onto cart at the Columbia Army Air Base in 1942 (Photo courtesy of William A. Hamson)

The Doolittle Raiders’ B-25s on the flight deck of the USS Hornet on their way to bomb Tokyo in April of 1942 (Photo courtesy of U.S. Air Force)

The old Columbia Air Base Officers Club (Photo courtesy of William A. Hamson)

David Thatcher, far right, and the crew of the Ruptured Duck, one of 16 bombers that took part in the Doolittle Raid over Japan in 1942 (Photo courtesy of U.S. Air Force)

Mission commander Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle accepts a medal from the skipper of the USS Hornet, Capt. Marc A. Mitscher. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Air Force)

An electric suit used by crew in high altitudes to combat low temperatures, nicknamed “bunny suits” (Photo by Sammy Sobich)