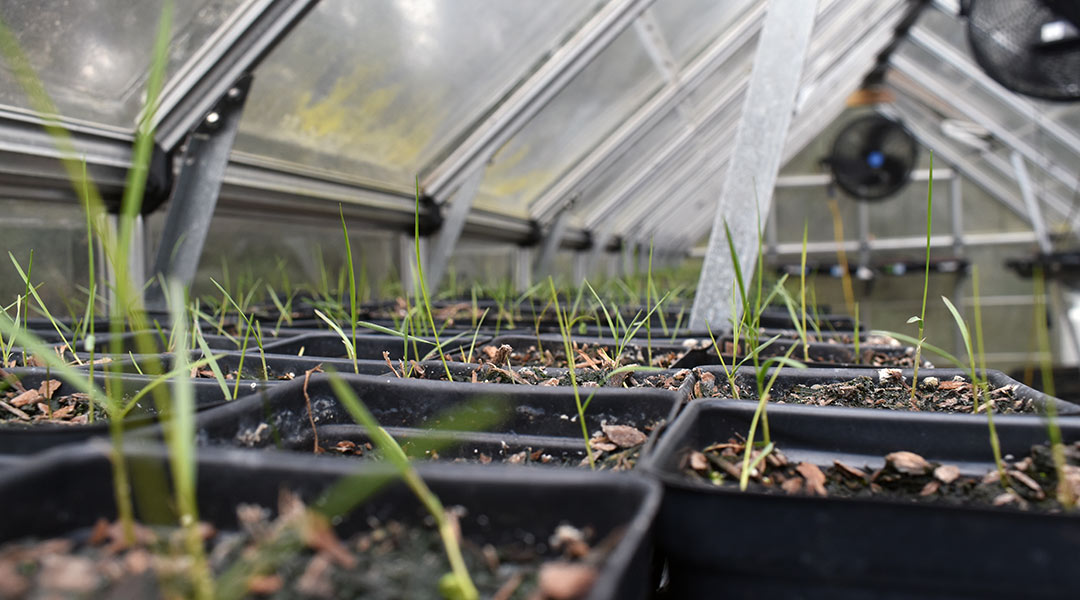

These seedlings could grow up to 8 feet tall, and their deep root systems provide the foundation for salt marshes. (Photos by Danielle Cahn)

More than 4,000 feet of the heavily developed Charleston coastline are better protected from flooding thanks to an unlikely hero: smooth cordgrass.

Smooth cordgrass, or Spartina alterniflora, is an essential ingredient to healthy salt marshes, which act as natural flood barriers, water filtration systems and nurseries for marine wildlife.

“The oyster reef will help deposit sediment and mud behind the reef, and that marsh grass will use its root system to pack in and hold the mud together,” said Kelly Lambert, a natural resource technician at the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources. “So they really work hand-in-hand together to protect our waterways and provide habitat.”

After severe “dieback” events during droughts in 2012 and 2016, large areas of Charleston’s salt marshes were left stripped and vulnerable to erosion, according to research by environmental groups. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration awarded a grant for salt marsh restoration to DNR in 2019. Now, after forging partnerships with local coastal conservation organizations and four years of hard work, the project is coming to a close.

Organizers, which also include the S.C. Sea Grant Consortium, S.C. Aquarium and the Clemson University Cooperative Extension, said the impacts have been obvious.

“The project in total will create about 2.3 acres of new habitat and estimated salt marsh habitat,” said Peter Kingsley Smith, the shellfish research section manager for SCDNR. “One of the big benefits of this project is we’re making a really close connection in space between people that are living in a highly developed area … (and) the use of nature-based approaches to protect and conserve habitat and provide protection against things like sea level rise and increased storminess, both of which are very prevalent hazards in the Lowcountry.”

Many members of the Charleston community have volunteered to help by collecting seeds, growing the seedlings and transplanting them in marshes.

“There’s a huge interest in this ecosystem, which is really positive,” said E.V. Bell, the marine education specialist for the Sea Grant Consortium. “There’s just this wonderful community ethic, I guess, or a stewardship ethic is probably the best way to say that … that people are really, really wanting to help.”

DNR said across their coastal conservation projects in Charleston, they get thousands of volunteers every year.

One of those volunteers, who was working on planting cord grass seedlings, said she experiences the effects of degrading salt marshes every day.

“I live on the marsh and have a vulnerable bank,” said Nina Fair, a Charleston local and repeat volunteer for SCDNR, “I catch crabs, and my shtick is kinda making devil crabs. And I really noticed the difference this year.”

Fair’s personal experience living in Charleston made the importance of the salt marshes obvious to her.

But event organizers say people who come to volunteer are often learning about them for the first time.

“There’s avid fishermen and avid people who are on the water a lot and kind of have heard about our program and what we do,” said DNR’s Lambert. “But there’s also a lot of people who live here who have never heard about it. And, it’s like, when you get to see those wheels turning and the light turn on, it’s exciting to be able to help connect those dots for people.”

As the restoration project comes to a close, organizations that are involved are committed to continue fortifying coastal ecosystems.

“We feel like we’ve really built some nice community momentum to helping us not only restore the salt marsh, but also understanding the importance of it,” said the Sea Grant Consortium’s Bell. “We’re definitely not going backward in our participation. We tend to grow a little bit each year.”

DNR has already started on a new marsh restoration project in West Ashley. It received $1.5 million from the National Coastal Resiliency Fund in September of 2022 to create new oyster reefs and plant even more smooth cord grass. The S.C. Oyster Recycling and Enhancement program is leading the effort. That program also is taking volunteers to dig out canals for improved drainage in March.

Coastal conservationists hope that despite increasing development in Charleston, the salt marshes can continue to thrive.

“A big problem for South Carolina and Charleston is just the construction that’s going on, the amount of people that move here, it all is going to impact the marsh,” Lambert said. “We need to at least do our part to help protect it. We can’t tell people to not move here. It’s a beautiful place to be.”

The sediment trapped in the cordgrass’ root systems acts like a sponge for excess water, mitigating the effects of rising sea level and severe storms.

Salt marshes provide a protective habitat for many of South Carolina’s aquatic species, including this crab.

Volunteers for S.C. Department of Natural Resources take cordgrass seedlings germinated over the winter and pot them to grow in green houses. They will be transplanting the grass later in the spring into degraded marshland.