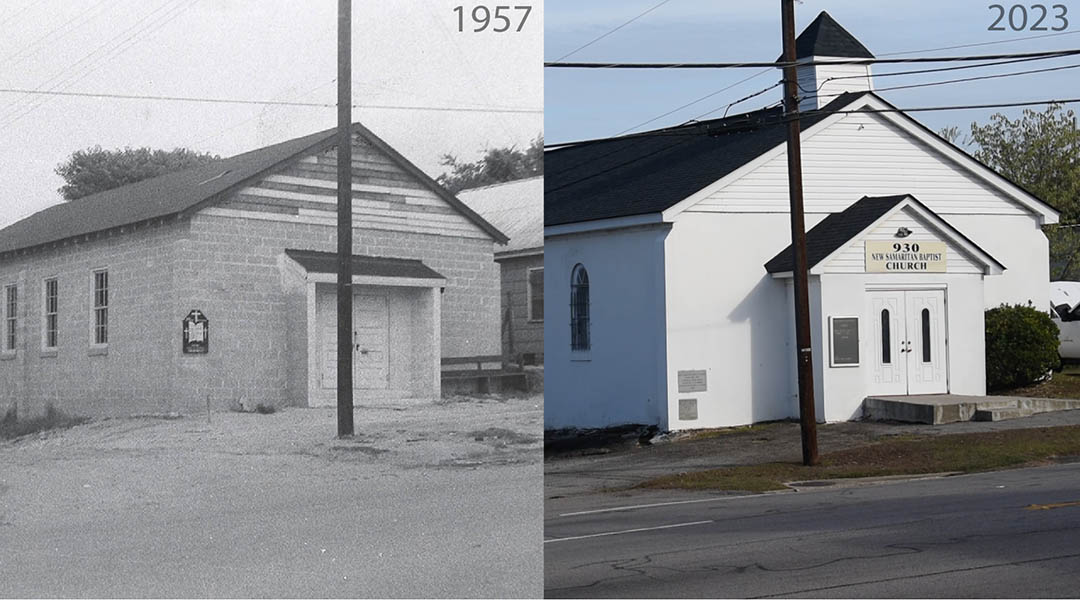

New Samaritan Baptist is the only Ward One church that didn’t relocate after 1968. (Graphic by Win Hammond/Carolina News & Reporter. Photo courtesy of the South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina)

Some of the city of Columbia’s biggest attractions sit in the shadow of the Statehouse.

The Vista, Colonial Life Arena and the Darla Moore School of Business are down the hill west of Main toward Huger Street.

But before any of those Columbia institutions were built, there was a predominantly Black neighborhood there known as Ward One where “everybody knew everybody.” Residents were moved out of the area in 1968 to make way for University of South Carolina development.

Many of the residents reunited and founded the Ward One organization in 1992, 24 years after the neighborhood was torn down.

The organization continues to host a bi-annual reunion at one of the seven churches that were relocated.

Neighbors and friends got to know one another again, even forming new connections.

The people who lived in Ward One remember the shock of displacement.

They’re aging now.

But they aren’t bitter. And they’re still fighting to preserve their beloved bygone community.

What was Ward One?

Ward One takes its name from its voting precinct, an area roughly bound by Huger, Heyward, Main and Gervais streets.

The neighborhood was predominately Black by the 1930s. Residents worked in mills, warehouses and railroads.

The unpaved streets where children played football or hopscotch were lined with small wooden houses. Some were home to more than a dozen people.

Community members said that Ward One was a tight-knit, albeit poor, community, hemmed in by heavily traveled city streets, former residents said.

Raymond Richardson, 75, remembers selling sodas and other snacks with his siblings at baseball games. Selling concessions, running a general store and a barbershop out of their home were some of the ways his family got by.

When he was a sophomore in high school, he worked 40 hours a week in one of the nearby mills.

He said working at baseball games was the most fun and the biggest source of pride he got from growing up in Ward One. His parents didn’t have enough money to buy him nice clothes for church, so he and his siblings earned it themselves.

Kids would go to school at Booker T. Washington High School and the Celia Dial Saxon School on the corner of Assembly and Blossom streets.

In 1968, Ward One came to a sudden halt. Residents were told to leave as USC planned to build the Carolina Coliseum.

Homeowners sold to the city, some pushing back against what they called the less-than-market rate offered. Renters simply moved.

“We were devastated,” said Delores English, 80. “But what could we say? That was the university.”

She was only 15 years old and was born in a house on the corner of Senate and Park streets. She grew up a block from the Statehouse.

Her parents were one of the few Ward One homeowners, and her father owned a restaurant on Gervais called Bell’s Lunch.

She and her siblings helped their father sell hamburgers, bologna and smoked sausage sandwiches.

After their home was bought for below-market rate, they moved, she said. She now lives in the Greenview neighborhood north of downtown.

How it’s remembered

The community’s resilience gained attention and has been written about often as part of Columbia’s Black history.

USC students walk past Ward One memorials every day, many no doubt missing their significance.

Though Ward One no longer exists, signs of it still live.

The corner of Blossom and Park streets is labeled Ward One Way, for example, and a historic sign marks the site of the former Saxon school next to USC’s Strom Thurmond Wellness and Fitness Center.

In April, the university renamed one of its Lincoln Street dorms after Celia Dial Saxon, a prominent Black educator who ran the school.

The dorm is the first university building to be named after a Black person, according to the university.

Some community members don’t pay much attention to the city’s markers.

Reverend Veronica Bailey, 65, said the markers are “not enough.”

Instead, Bailey tells her children and grandchildren about what the area used to be, what churches were there, where she played as a kid, who she knew on those streets.

She admires Ward One residents who have avoided carrying a chip on their shoulders despite what many see as an injustice.

“It speaks to who we are as a people,” Bailey said. “If we harped on this or harped on that, it really wouldn’t get us to where we needed to be.”

Richardson said he’s thankful to be where he is and doesn’t pay attention to negativity about Ward One being demolished.

“I can’t be narrow-minded and think about, ‘What if?’” Richardson said. “All I can do is move along with the progress, and make progress myself.”

He stays busy now but keeps remnants of Ward One close.

Richardson’s home is decorated with old photos of his neighborhood and his 15 siblings.

One of the bedrooms has piles of Ward One memorabilia such as a Booker T. Washington sweater from a 1946 graduate of the high school.

Ward One now

USC, especially with the help of history professor Dr. Bobby Donaldson, makes sure the neighborhood hasn’t disappeared.

“I teach classes on Ward One and invite the Ward One and Wheeler Hill families to participate,” Donaldson said in a podcast with USC. “I’ve mentored students who’ve done Ward One projects, and so now 50, 60 years after these families find themselves leaving their neighborhoods, they are able to return to some degree.”

The Palmetto Compress building is now an apartment complex, but it used to be a big employer for Ward One residents.

Workers processed thousands of cotton bales for textiles in the building. Now, USC students live in it.

In 2015, the complex began renting units as commercial and residential property, while also displaying Ward One history.

Richardson and the Ward One organization visited the Palmetto Compress apartment building last year.

Richardson said he talked to one of the security guards who was Black. The guard looked into the display with the visitors. She had never met the members.

She joked and chatted with Richardson. She told Richardson she was born and raised in Columbia.

They walked through the compress exhibit where it told a small part of the neighborhood’s history she had no idea about before taking the job.

Richardson said the security guard saw her father in one of the photographs. He was holding her brother in his lap and a toddler on his arm in front of a narrow, wooden house.

The significance of the neighborhood’s history materialized: She realized the toddler in the photo was her.