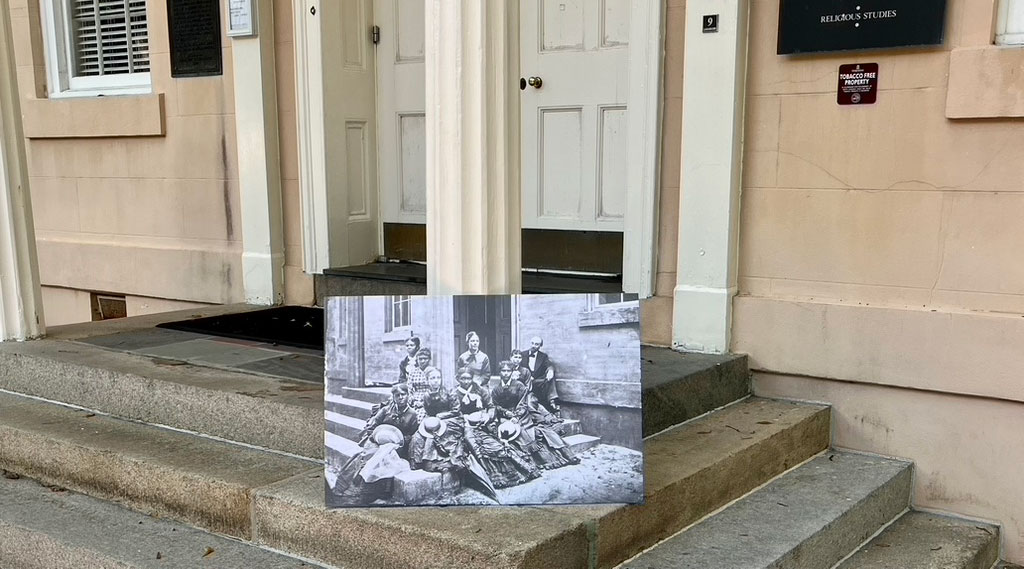

A photo of the only graduating class from the Normal School, taken in 1877 on the steps of Rutledge College on USC’s Horseshoe. (Photo courtesy of Christian Anderson/Carolina News & Reporter).

One small school that opened 150 years ago and served primarily African Americans had a big impact on how teachers are educated even now in South Carolina.

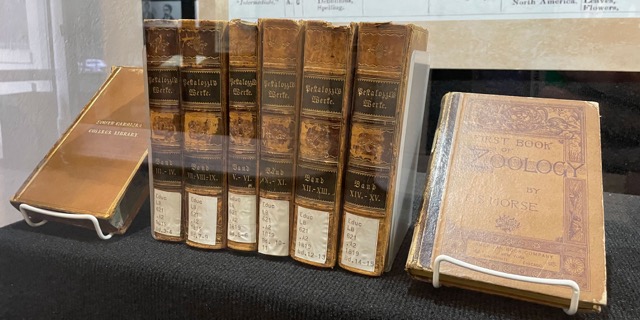

An exhibit at the University of South Carolina’s College of Education is celebrating the State Normal School, which was founded in 1873 and lasted three years.

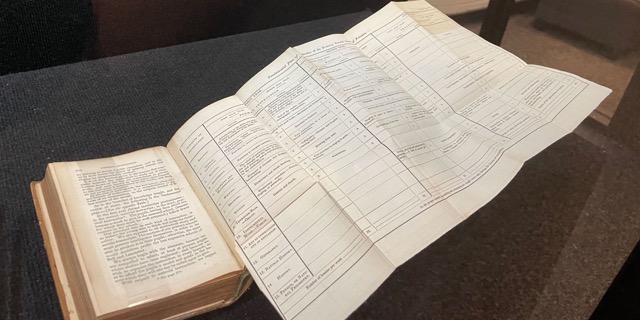

The display, at the Museum of Education, describes how the school became the foundation for teacher education and training in the state’s public schools.

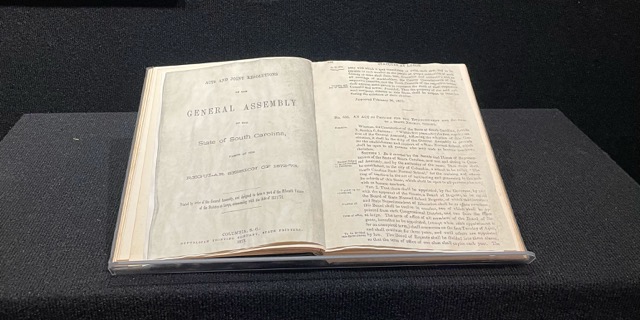

The South Carolina State Normal School was established by the state’s General Assembly during Reconstruction, a time when Black residents cross the country were experiencing new freedoms, holding office and seeking higher education degrees.

Dr. Christian Anderson, who teaches about higher education at USC, curated the exhibit on the school. Anderson wanted to show “how professional it was, how critical it was and what kind of teachers came out of it.”

The show opened Sept. 5 and runs through December.

The school’s first board included Francis Cardozo, Henry Hayne and Robert Smalls, three Black men who helped write the state constitution of 1868. The men were also on the education committee that created the school and wrote in the state constitution that the school “shall be open to all persons who may wish to become teachers.”

It opened Sept. 1, 1874 – nearly a year after Hayne enrolled at USC – with 31 students, predominantly Black women. The school held classes in the Rutledge College building on USC’s historic Horseshoe.

“I think it’s important to understand this history and know more about this history in general,” Anderson said. “And just like (Cardozo, Hayne and Smalls) argued in 1868 that education is a fundamental bedrock part of who we are and critical to our citizenship, the same is true today.”

Tyler Parry, an associate professor of African-American and African diaspora studies at the University of Las Vegas, learned about the Normal School while enrolled at USC as a graduate student.

“It became pretty clear to me that there was a unique history that simply just was not part of the grand narrative of the states,” Parry said. “This happens often with stories of marginalized people. They just are not part of the official narratives for much of their existence.”

Mortimer Warren, the school’s principal, had a “dedication to professionalism, to professionalizing teachers,” Anderson said.

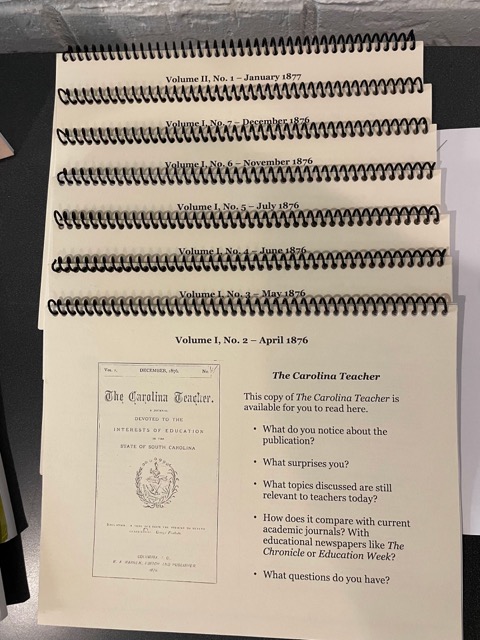

Warren displayed his devotion to the school through The Carolina Teacher, a publication that he wrote and edited.

“I stumbled across this mention of The Carolina Teacher, and I was like, ‘What’s that?’” Anderson said of his research. “So I asked the archives to pull it out.”

Anderson said he was expecting something “really small and not all the great.” He was shocked by the publication, calling it “somewhere between an academic journal and a professional news publication.” He wanted to include the publication in the exhibit to “highlight the fact that this was a successful publication.”

“Because you don’t put advertising in a stinker,” Anderson told the Carolina News & Reporter.

While the school only lasted for three years, it graduated one class of eight women. One of the graduates was Celia Dial Saxon. She taught in Columbia schools and “became the most memorialized African-American woman in South Carolina,” according to Dr. Alexandria Russell, who’s also a W.E.B. Du Bois Research Institute Non-Resident Fellow at Harvard University’s Hutchins Center for African & African American Research.

The school’s history can be applied today, Parry said.

“The value of education and – particularly nowadays, when there’s all these attacks against ethnic studies – programs that elevate the experiences of marginalized people, particularly people of African descent, we do have a precursor to understanding how you deal with that,” Parry said. “And when it comes from women, like Celia Dial Saxon and Clarissa Allen, who against all odds during the Jim Crow period, still found value in going out and educating young people in their community.”