The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline offers free, 24/7, year-round help for those in crisis. (Photo by Mary Gaughan/Carolina News & Reporter)

“Isolated,” “lonely,” “disconnected” — these are words older adults in Richland County used in suicide letters to describe how they felt before taking their lives.

Those suicide letters have become all too common in Richland County, where suicides have jumped sharply during the past two years.

Richland Coroner Nadia Rutherford said many letter writers were elderly and struggled to maintain human connections or to get mental health help.

“They were expressing in the suicide notes they left behind that they felt like a burden to their families,” Rutherford said. “One note, in particular, talked about how their families never come to visit.”

As of late August, Richland already this year had seen 49 lives lost to suicide, according to county records.

Those 49 deaths already have exceeded the 47 recorded in 2022 and are on track to surpass the 72 in 2023.

It’s unclear if South Carolina’s other counties are seeing the same recent trend. State and national figures for 2023 and 2024 are not yet readily accessible to the public .

In Richland, last year’s surprising jump to 72 was the start of what threatens to become a troubling epidemic.

“It was eye-opening,” Rutherford said. “We are unfortunately on track to exceed that this year.”

The coroner’s office does not provide a detailed breakdown of the ages of those who have died from suicide. But Rutherford said their ages ranged from 13 to 91 with a “shocking” number of senior citizens.

She said some individuals expressed feelings of abandonment, especially if they couldn’t get around as well as they used to.

“They felt like they were abruptly forgotten about as members of the family,” Rutherford said. “They weren’t invited to family vacations or gatherings. The only time families would go to visit them is when they’re going to doctor’s appointments.”

Addressing the barriers

A representative from South Carolina coroners’ offices attends the scenes of unusual, suspicious or violent deaths.

But coroners also look for safety trends and advice for county residents in how to prevent deaths whenever possible.

Part of the problem with the recent spate of suicides, Rutherford said, is a shift in technology that has left behind some elderly people who aren’t as technology savvy.

Many mental health services, for example, are accessed online. But that can be difficult for some senior citizens.

Chava Raymes, a South Carolina-based therapist for Blue Moon Senior Counseling, said the technological barrier might push some senior citizens away from seeking help.

“I think it seems scary for them,” Raymes said. “Senior adults tend to be a lot more leery of technology in some ways, which is totally fine. But they don’t fully understand how to use these resources.”

Rutherford suggests mental health professionals are overlooking the older population, as most resources are geared toward younger people.

“I think that’s why we’re having this jump,” Rutherford said. “There is just a big disconnection between this generation and the folks who are aging.”

Rutherford also said there’s a dwindling number of mental health services in general, especially counselors.

“There aren’t a lot of free and readily available resources,” Rutherford said. “There may be a six-month waitlist, and by the end, you’re already deep within the crisis.”

The stigma surrounding mental health also could be keeping some from getting help.

“Especially with older men, there’s a stigma, like, ‘Oh, you don’t need help. You’re not sad. You’re not depressed,’” said Jessica Barnes, program manager for the Office of Suicide Prevention at the South Carolina Department of Mental Health.

Some don’t want to be a “burden to other people,” especially their families, Raymes said.

“They oftentimes find it embarrassing, especially if they spent their whole adulthood being independent. They forget how to ask for help,” Raymes said.

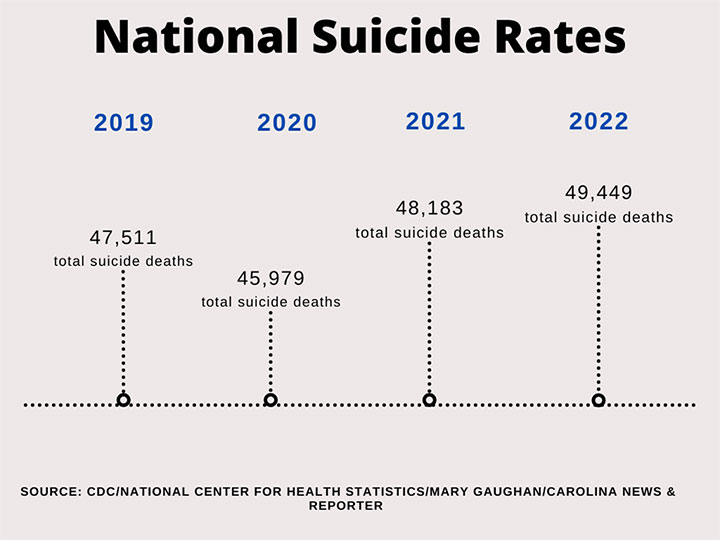

John Tjaarda, South Carolina area director for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, noted suicide rates decreased nationally during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

He suggests the decline was due to people being more focused and connected.

“They were playing commercials on repeat that said, ‘It’s OK to not be OK,’” Tjaarda said. “They were talking about reaching out to loved ones who were isolated. And that decline in national suicide proved what works — having a deep sense of community and connection.”

Tjaarda said national suicide rates increased again in 2021 as COVID-19 began to subside.

“With the pandemic starting to wane, so did the sense of connectivity,” Tjaarda said. “So, in my opinion, we saw what a country in a world focused on connection can do.”

Rutherford said reminding people in our lives their presence is appreciated can go a long way.

“We are literally losing members of our community, and the numbers are increasing,” Rutherford said. “We have to keep showing these folks how much they matter. We need to give them a life and a purpose outside of sitting in their homes patiently waiting every day for someone to notice that they’re still there.”

Recognizing signs, providing support

Tjaarda said mental health and suicide are extremely complex and affect everyone differently but can come with subtle warning signs.

“If you notice someone suddenly withdraw from something they love, like an elderly person that loves to attend bridge club, that can be an indicator that comes up close to a time of a crisis,” Tjaarda said.

Elderly people sometimes struggle to accept more dependence on others, Barnes said. And a loss of mobility can also lead to self-isolation.

Senior citizens’ family members and friends can often help in ways they might not realize.

Tjaarda said directly asking people if they are thinking about committing suicide is an effective strategy for normalizing discussions around mental health struggles.

“A lot of people think that is going to put the thought in their head, but our research has shown that’s not true,” Tjaarda said. “What happens is you’ve just taken this super taboo thing they thought they couldn’t talk about and made it OK for them to discuss. You’ve created a safe space for them to share their feelings, fears and hurts, allowing them to be open about their struggles.”

Raymes said her therapy sessions with older adults primarily focus on acceptance and control.

“I think the loss of control leads to a lot of anxiety and feelings of worthlessness,” Raymes said, noting that some grow to wonder, “‘What’s the point anymore?’”

Destigmatizing mental health at all ages and ensuring senior citizens have access to the resources they deserve is the first step, she said.

“In all actuality, I don’t think humans were ever meant to do it alone,” Raymes said. “In so many ways, we do need each other. And we need to learn how to ask for help at all ages.”

Barnes said that although it’s cliché, suicide prevention takes a village.

“There have been many times where it just felt like I was in the right place at the right time, but it truly is a community effort,” Barnes said. “But I carry around my hope, and I hold the hope for others, even if they don’t feel like they have it.”

The South Carolina Department of Mental Health in Columbia is one of 16 centers across the state. (Photo by Mary Gaughan/Carolina News & Reporter)

(American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, South Carolina Department of Mental Health, Blue Moon Senior Counseling/Mary Gaughan/Carolina News & Reporter)