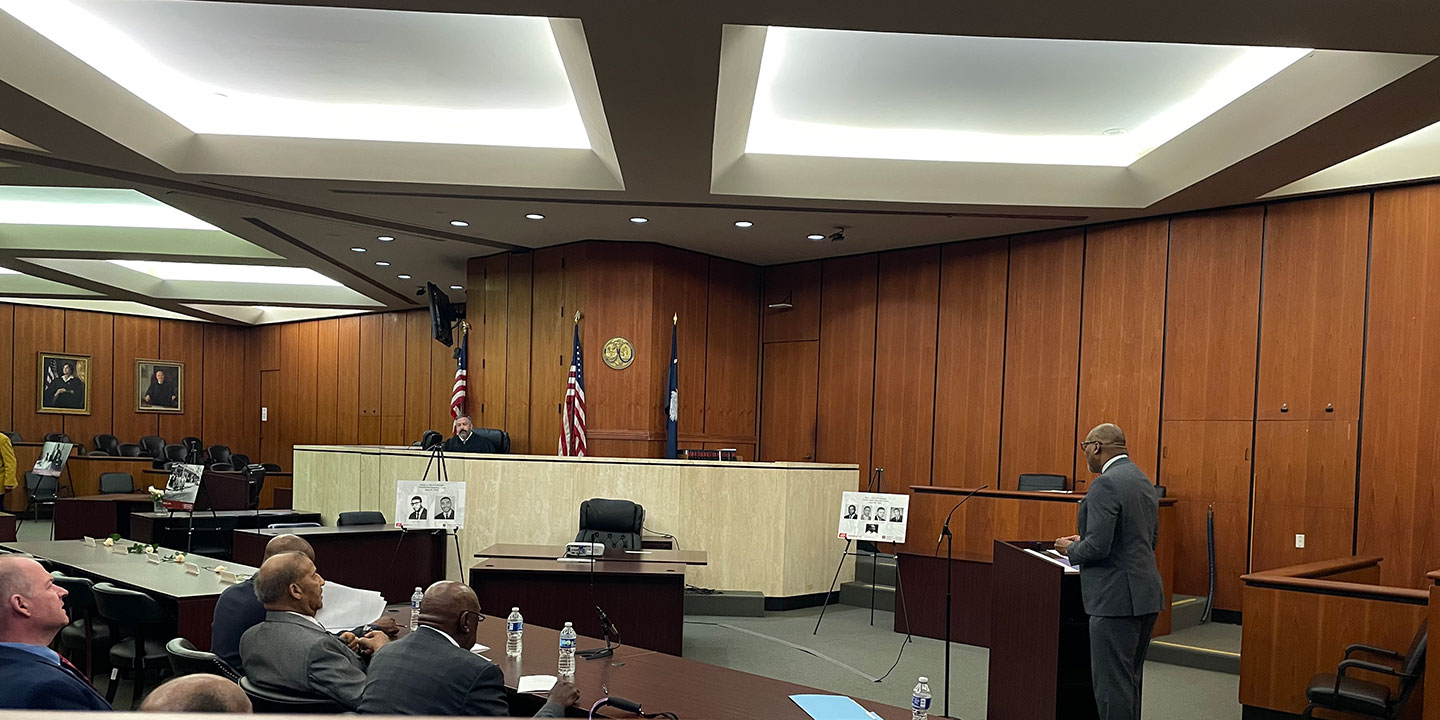

Rev. Simon Bouie makes remarks during the expungement ceremony on Oct. 25. (Photos by Ky Villegas/Carolina News & Reporter)

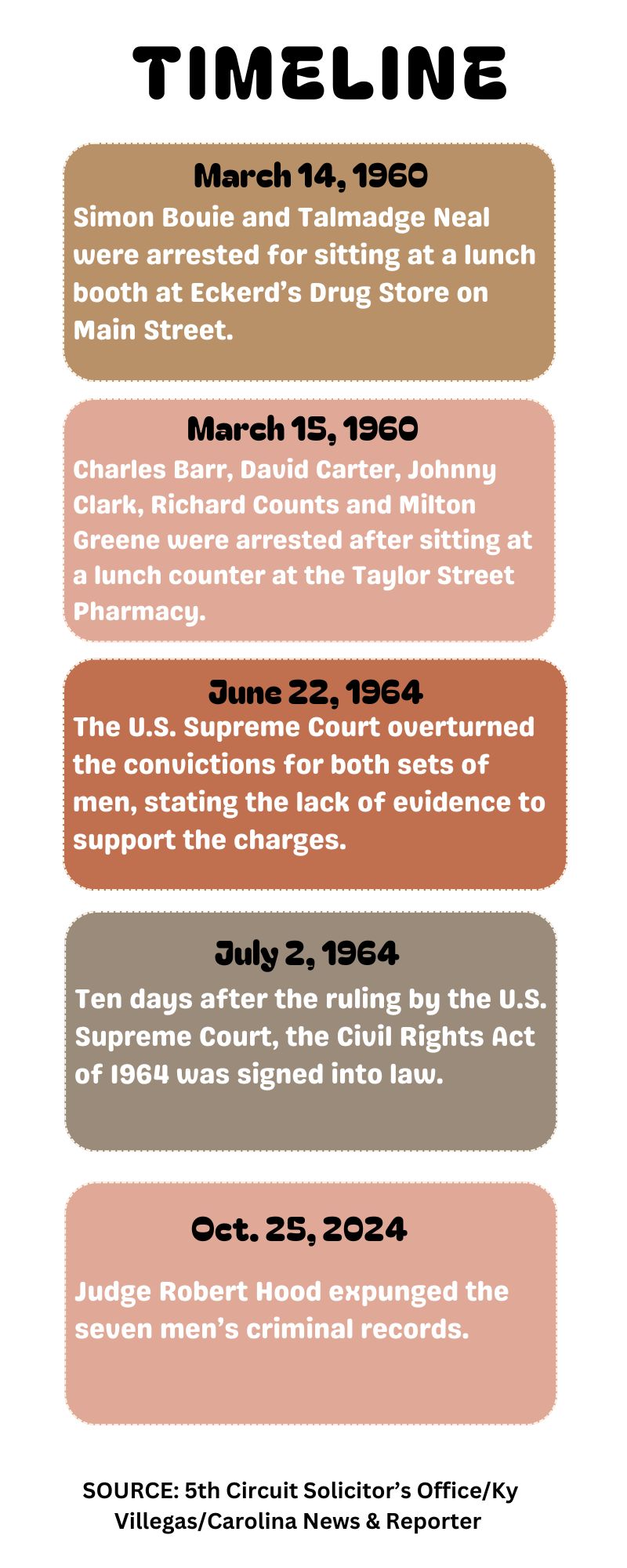

The Revs. Simon Bouie and Talmadge Neal were college students when they were arrested for sitting at a drugstore lunch booth in March 1960.

“Neal, I think we (are) in trouble now,” Bouie said, retelling the story of his arrest. “He said to me, ‘Well, I told my mom I wasn’t going to get involved in anything.’”

The two were charged with trespassing and breach of peace March 14 after refusing to leave. Five more students – Charles Barr, the Rev. David Carter, Johnny Clark, Richard Counts and Milton Greene – were arrested in Columbia on the same charges at a different drugstore lunch counter the next day in what came to be called a “sit-in.” Their crimes? Being Black and trying to eat at a “whites only” lunch counter.

Bouie and Barr – the only survivors of the seven men – stood in a different courtroom 64 years later to watch the expungement of their criminal records.

“I’m so glad I lived long enough to see this day come,” Bouie said.

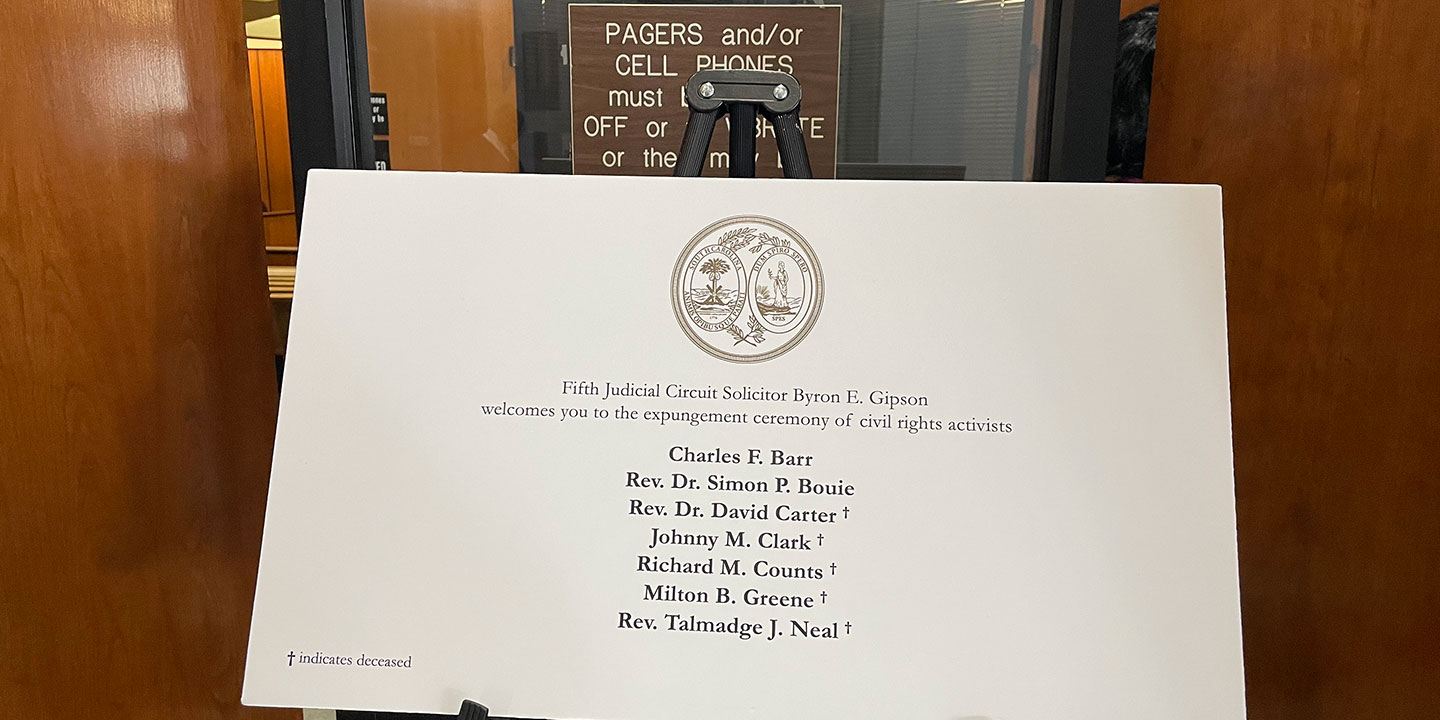

Circuit court Judge Robert Hood expunged the records of the seven civil rights activists at a courtroom ceremony Oct. 25.

The ceremony was hosted by the 5th Judicial Circuit Solicitor’s Office and the University of South Carolina Center for Civil Rights and Research. More than 100 people gathered to watch the ceremony at the Richland County Judicial Center, including Columbia Mayor Daniel Rickenmann and City Councilman Tyler Bailey.

Bouie and Barr were present and spoke. The other five had their records cleared posthumously. Bobby Donaldson, executive director of the center and associate professor of history at USC, spoke for the five men who have passed away.

“We gather to witness an extraordinary moment in history,” Donaldson told the court. “It is humbling to sit today at a table with Charles Barr and Simon Bouie. … We gather today in this courtroom to mark not just the moment in legal history but a profound act of justice and remembrance for our community.”

Fifth Judicial Circuit Solicitor Byron Gipson petitioned Hood to “right the wrongs” by expunging the records.

“We’re here today, your Honor, asking that you sign these orders – expunging these records, clearing these records,” said Gipson, who is Black. “Because I couldn’t stand before you in this court without the work of these men and others did. I couldn’t stand before you making this ask without that work.”

After he signed the records, Hood said the activists’ “unwavering commitment to justice serves as a beacon of hope and inspiration.”

“We recognize that these records do not define who they were or what they accomplished,” Hood said. “Instead, they remind us of the systemic barriers in the resilience they embodied. Each name today represents a story: the struggle, the strength and triumph over adversity.”

The impact of the sit-ins reached further than Columbia. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was enacted 10 days after the U. S. Supreme Court overruled the convictions.

The city of Columbia presented proclamations afterward to the activists. The proclamation said in part, “The records of the convictions should have been removed from city and state records. They were not. The court proceeding to formally remove, or expunge, the records is a welcome event in our city,” according to a State newspaper report.

“One day when it’s all over, history will call the names,” Donaldson said. “History will call the names of Simon Pinckney Bouie. It will call the name of Talmadge Javon Neal. History will call name of Charles Fulton Barr, the name of David Carter, the name of Johnny Milton Clark, the name of Richard Monroe Counts, the name of Milton Bernard Greene. And history will say, ‘Well done.’”