A recent pneumovirus outbreak led the Columbia Animal Shelter to temporarily limit intakes of dogs as there is no vaccine for the virus.

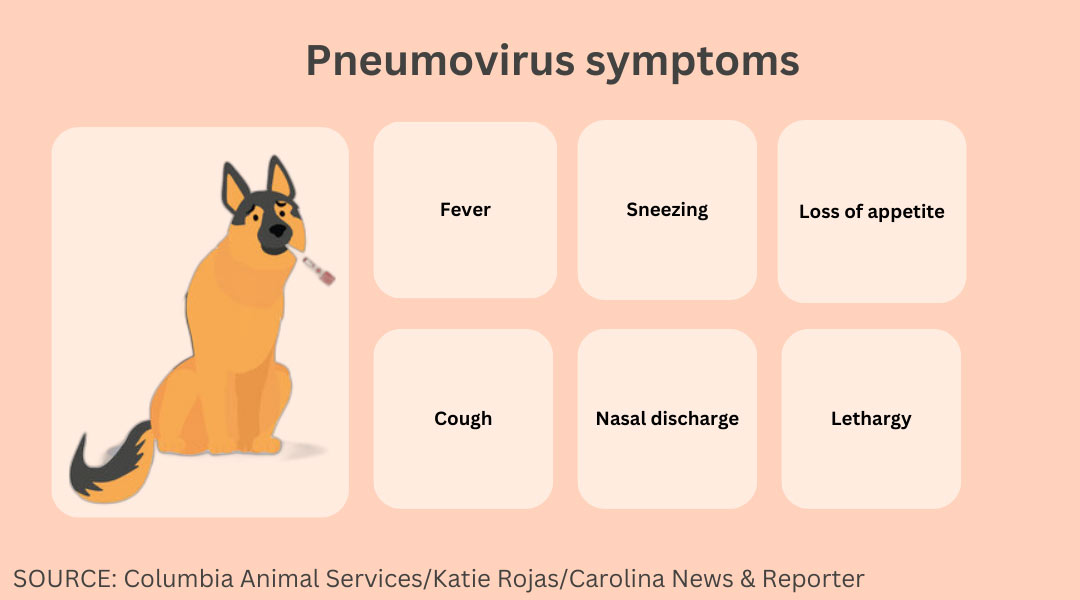

Pneumovirus is a canine respiratory illness that causes coughing, sneezing, nasal discharge and difficulty breathing, according to Columbia Animal Services.

The city of Columbia released a statement on Oct. 14 saying the shelter was only taking in dogs that were sick, injured or faced animal cruelty.

Staff and visitors were still allowed inside the facility. But operations were adjusted to limit the risk of spreading illnesses among the dogs. Infected dogs were isolated to minimize exposure among healthy ones.

While the virus only affects dogs, it could easily spread from volunteers to dogs outside of the shelter. The staff wanted to make sure the virus didn’t spread outside the shelter and encouraged fostering medically cleared dogs so the shelter could provide space for sick dogs.

And the staff wants to educate people to help dogs get better quicker and to help keep the virus from spreading.

The shelter said it thinks the virus was brought in from an outside source.

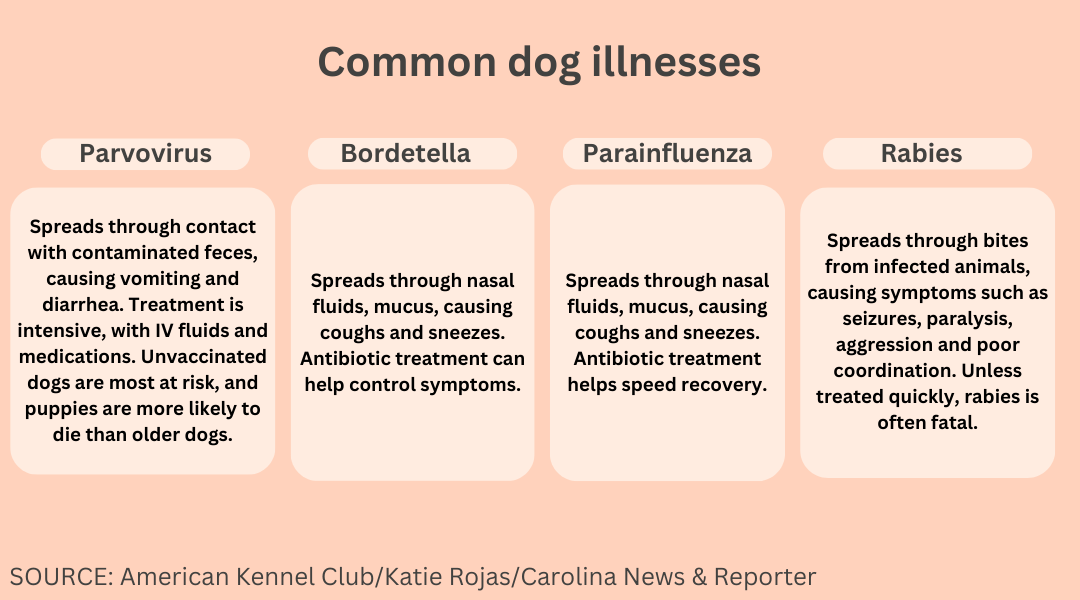

“Parvovirus is typically the only kind of confirmed outbreak we ever deal with, and those pop up all through the year,” Columbia Animal Services said in the statement.

Respiratory diseases can be transmitted onto people’s clothes even if the dogs don’t make direct contact with each other, said Jeff Seay, medical director of Well Pets Veterinary Clinic in Irmo.

While volunteers were still able to visit, Seay said they should take preventative measures if they have a dog at home.

Changing clothes and washing hands is recommended before volunteers go home to their pets, Seay said.

Pneumovirus is not a major concern for dogs who are vaccinated and healthy. But Seay said if his dog was older and had underlying health conditions, he might avoid areas where there are a lot of unfamiliar dogs.

The virus was cleared the first week of November, allowing the shelter to fully resume all operations, according to Justin Stevens, the city’s media relations director.

The shelter did not respond to an interview request but released a statement on its protocols for handling viruses.

“In an overpopulated area – such as shelters – disease control is very challenging,” the statement stated. “It is common to have an infectious disease at any given time. This is one reason we encourage community sheltering, spay and neuter, fostering and volunteer support to reduce overcrowding in shelters.”

“A lot of these respiratory infections happen when you have a large number of dogs housed in close proximity,” Seay said.

While the virus was contained to the shelter, veterinarians shared advice to owners and shelters for potential future outbreaks.

“Some of these respiratory infections may have an incubation period from one week up to even as much as two weeks, where they could potentially spread the disease without necessarily showing it,” he said. “The last thing you want to do is to expose your pet.”

Vaccinations don’t guarantee full immunity. But it’s the best preventative measure that veterinarians can take, said Steven Marks, dean of the Clemson University College of Veterinary Medicine.

Vaccinating pets against known respiratory diseases could help reduce the risk of severe illness, even if there’s no vaccine for pneumovirus, Seay said.

Dogs also can be infected with multiple diseases at the same time, such as canine influenza or Bordetella.

Vaccinations help protect pets from getting multiple infections at once, making them more likely to recover, Seay said.

It can be hard to tell the severity of the illness because the clinical signs often mimic other conditions such as an allergic reaction, Marks said.

“The kennel cough and pneumovirus’s clinical signs overlap,” he said. “They’re not all the same.”

Marks said veterinary medicine is like pediatric medicine, as both involve patients who cannot communicate their issues and caregivers who are worried about the patients’ well-being.

Fact or myth?

There was no way to prevent the virus, Stevens said.

The shelter began accepting more animals on a case-by-case basis once it was able to control the virus.

Dogs received over-the-counter medications and fluids to manage symptoms. It is a timely process and similar to treating a cold in humans, Stevens said.

Veterinarians in the Midlands advise dog owners to contact them directly for guidance instead of relying on online information.

It is very rare that anything will pass from dogs to humans or cats. Illnesses tend to stick within the specific species, Seay said.

“Dogs, just like humans, are social animals. Illnesses will arise even if we take all the appropriate precautions,” said Haley Hunt, medical director of Grace Animal Hospital in Lexington. “I advise owners to not live in fear of contracting an illness but to be mindful of how they can spread.”

The way dogs interact is different from how people interact, which makes it easier for diseases to spread, Seay said.

“You don’t go up to a person you just met and sniff their nose, right? That’s the way dogs interact,” he said.

Seay said a common misconception in viral infections is if there isn’t a vaccine for a particular virus, then vaccines are pointless.

One of the places at risk, besides shelters, is boarding facilities. Many owners’ mindset is they’ll only get the vaccines that the boarding facility requires, he said.

If a boarding facility requires the Bordetella vaccine but not the canine influenza vaccine, it’s even more essential for pets to receive the canine influenza vaccine, Seay said. That is because “it’s likely that the dog in the neighboring cage will not be vaccinated against canine influenza.”

Some owners may believe antibiotics are necessary for all infections. But they can’t relieve viral infections – they relieve bacterial infections, he said.

Sometimes veterinarians can’t determine the exact cause of an issue. But they focus on improving the pet’s condition.

Seay said a 100% diagnosis for every patient would be ideal, but veterinarians learn to identify conditions and their treatments.

“There’s often a lot of overlap,” he said. “So, we treat what we can, and the pet gets better.”

Lessons from the past

Canine pneumovirus was first identified in 2010 during a study on respiratory diseases in dogs at U.S. animal shelters.

There have been recent outbreaks in animal shelters in Florida, Alabama and now Columbia.

Viral outbreaks may be a concern, but past experiences help craft practices on how to deal with it.

Increased travel post-COVID raised the risk for respiratory illnesses in the dog population since owners need to board their pets during vacation, Hunt said.

Dogs may face serious complications if they are older or have underlying conditions such as cancer, diabetes or heart disease, Seay said. While healthier dogs can recover, those with pre-existing conditions are most at risk.

Cindy Connelly, owner of Lads and Lassies in Columbia, a dog daycare and grooming facility, has dealt with previous outbreaks within the business.

“You always have to be cautious,” she said. “I’ve been doing this for 35 years. It’s all about keeping things clean and making sure that your animals are up to date on all of their vaccines. The biggest thing is to make sure you disinfect.”

Outbreaks can come from anywhere. A customer’s dog that had Bordetella caught it while visiting a veterinary clinic, Connelly said.

The protocols for dealing with these viruses are similar to prevention measures for COVID – isolation and disinfecting areas, she said.

“The concept is to keep things clean,” Connelly said.