Park ranger Jon Manchester shows off the wingspan of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker using a model. Photos by Sebastian Lee

Fifty years ago, a whimsical boat voyage and the cry of a mythically rare bird led to the creation of Congaree National Park. Now, 77 years after its last confirmed sighting in 1944, that same bird, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, has officially been declared extinct.

In the spring of 1971, Alex Sanders and a group he described as “South Carolina’s infant environmental movement,” were looking for a reason to get the government to protect the Santee Swamp, the country’s last untouched old growth bottomland hardwood forest, located southeast of Columbia. The swamp and its valuable timber were being targeted for logging.

In an interview Monday, Sanders, a retired chief justice of the S.C. Court of Appeals and president emeritus of the College of Charleston, described how he scheduled “excursions” designed to bring press to the area, one of which was a plan to “discover” a Civil War train wreck, complete with cannonballs. In a state that revered the Old South, the group figured a Civil War site would certainly be preserved.

Eventually they would find their savior of the swamp, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. In a boat heading down the river, Sanders and members of the movement along with WIS television reporters played the call of the woodpecker in hopes to hear a response from a living one.

According to Sanders, everyone left the boat convinced that they had heard a reply.

“Hearing that cry was tantamount to finding an angel,” Sanders said.

Despite the crew’s certainty, no further surveys of the swamp revealed any signs of the ethereal bird, leaving many to wonder if it happened at all. Even today, Sanders is ambiguous.

“It doesn’t really matter whether it’s true or not,” Sanders, now retired and living in Charleston, said. “He was there when we needed him to be… that’s what this whole thing is all about.”

Sanders’ report, corroborated by those who were with him, drew international attention and compelled the U.S. government to establish Congaree National Park on the swampland.

“There’s nothing as powerful as public opinion, but it must be aroused, sometimes artificially,” Sanders said, chuckling.

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker was an “unmistakable” bird before its extinction, said Congaree Park Ranger Jon Manchester. Before extinction it was the third-largest woodpecker in the world, with a wingspan of nearly 3 feet.

“It’s enormous,” Manchester said, “so they called it the Lord God bird, because you saw it and you were [like], ‘Lord God, that’s a big bird.’”

Habitat destruction was the primary factor in the bird’s decline. In its prime, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker inhabited old-growth bottomland forests across the Southeast and parts of Cuba.

These forests, with large, hard trees and nearby sources of water, were ideal for logging and subsequent farming in the 19th and 20th centuries, Manchester said.

“There are little pockets of old growth left across the Southeast, but it’s just not enough for a species to be able to survive and continue on,” Manchester said.

The bird’s chances of survival weren’t helped by its ecological needs, which include large swaths of territory. One pair of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers, Manchester said, require as much territory as 130 pileated woodpeckers, a smaller but similar-looking variety of woodpecker.

“It’s a sad thing to have to say, yes, a bird is extinct, but it should also be an impetus to say okay, what can we do to try and make sure that other bird species don’t go the way of the ivory-billed woodpecker?” Manchester said.

Another South Carolina bird, the Bachman’s Warbler, was also declared extinct in the same U.S. Fish and Wildlife press release as the Ivory-bill Woodpecker. The Warbler could be found around Francis Marion National Forest in the coastal region.

Fortunately, there are many things that can be done to prevent bird endangerment. The largest and simplest, said Charleston Audubon Society President Jennifer Tyrell, is to keep your cats indoors.

“If you have a cat, or are getting a cat, keep it inside, or get it a catio, or leash-train it, because cats do quite a number on birds,” Tyrell said.

A report from the American Bird Conservancy found that household cats kill approximately 2.4 billion birds annually.

Turning lights off at night and marking windows can also save birds from endangerment. Millions of birds hit glass windows and die annually, Tyrell said.

The Audubon Society is also involved with replanting species of trees that endangered bird species use for their habitat, such as the longleaf pine, in order to combat habitat loss.

While these measures won’t resurrect the Ivory-Billed woodpecker, Bachman’s Warbler or other birds lost to extinction, Tyrell said that keeping our bird populations alive and well is essential.

“Where birds thrive, people prosper,” she said. “So if birds are thriving, then that means we have clean water, that means we have clear air, we have good natural resources.”

And there are those who are skeptical of the woodpecker’s extinction at all.

“There’s still the hope that there’s a relic population down in Cuba,” Manchester said. “There are people who have said it’s not extinct down there, but again, I don’t know how much habitat it has.”

And so, as it has for nearly 80 years, the search for the Lord God bird continues.

To hear the call of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker click here.

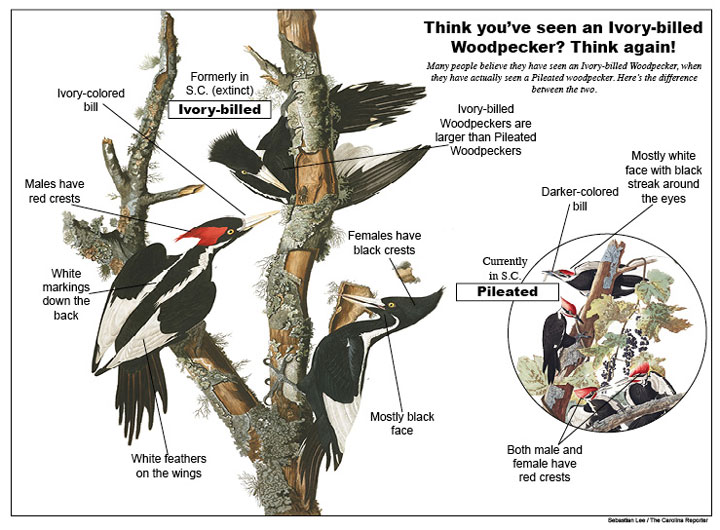

Manchester has been working at Congaree since 2013. Since then he says many people have come to him thinking they’ve seen an Ivory-billed Woodpecker when in actuality they’ve seen a Pileated Woodpecker.

“It’s enormous,” Manchester said, “so they called it the Lord God bird, because you saw it and you were (like), ‘Lord God, that’s a big bird.’”

Without the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, South Carolina may have never had Congaree National Park, the state’s only national park.

Artwork provided by the National Audubon Society.

ABOUT THE JOURNALISTS

Jack Bingham

Jack Bingham is a senior multimedia journalism major from Spartanburg, South Carolina, earning a dual degree in environmental science. Bingham strives to present scientific issues through a human lens, showing how phenomena such as climate change and pollution affect individual people. Bingham hopes to write for a publication that matches this mission, such as The Guardian or National Geographic. When he’s not in the newsroom, Bingham performs musical theatre and works at Riverbanks Zoo as an educator.

Sebastian Lee

Sebastian Lee is a senior Multimedia Journalism student from Graniteville, SC. Before Carolina News and Reporter, he has worked with the Daily Gamecock in both the news and arts and culture sections. He enjoys working with data and the reporting on the economy. Lee is a huge film buff and spends a lot of his free time at the movies or watching movies at home. He also minored in film and media studies. While he hopes to one day report on more serious news, Lee would be just as happy working for Rolling Stone magazine.