Abortion protesters stand outside the Planned Parenthood location Dec. 6 in Columbia. (Photo by Mollie Naugle/Carolina News & Reporter)

With the start of the 2025 legislative session just weeks away, abortion is a topic at the forefront of the minds of many legislators and South Carolina residents alike.

State lawmakers already have enacted a ban on abortions six weeks into a pregnancy, with exceptions for rape, incest and medical emergencies. The recent election, though, has given Republicans more power in the Legislature, potentially clearing a path for additional restrictive abortion laws and impacting the state of reproductive healthcare in South Carolina.

Inside the legislature

Rep. Jay Kilmartin, R-Lexington, is among Republicans who wants more restrictions.

“Two years ago we passed the ban on abortions after six weeks from conception,” Kilmartin said. “And that was a big win. But I don’t think it changed much. Women just go in earlier when they suspect they’re pregnant and get abortions. So, we’re going to push for life at conception and equal protection for the unborn.”

The Fetal Heartbeat Act, enacted in May 2023, prohibits South Carolina physicians from performing or inducing abortions after a fetal heartbeat is detected, which occurs around six weeks post-fertilization.

The law allows abortions within 12 weeks of pregnancy if the mother is a victim of rape or incest, as well as to prevent the death or irreversible physical impairment of the mother.

Under the act, physicians who perform abortions outside of the exempted circumstances can face up to two years in prsion and fines of up to $10,000.

The Human Life Protection bill would prohibit all abortions in South Carolina starting at conception, except in the case of medical emergencies.

The bill was presented last year in the House of Representatives and passed but did not make it out of the Senate. The bill was pre-filed Dec. 5 to be revisited in the upcoming legislative session.

“I believe we need to pass a bill that ends all intentional abortion of unborn children, ensuring that medical emergencies and miscarriages are not included in that net,” said Rep. Josiah Magnuson, R-Spartanburg. “You don’t want to draw it too wide of a net, but we do want to prohibit any unborn child from being intentionally killed.”

Some legislators also have shown support for 2023’s South Carolina Prenatal Equal Protection bill, which would allow women receiving abortions to be prosecuted for homicide.

That bill died after an increasing number of Republican legislators revoked their support for it, garnering national attention. It was refiled in the House on Dec. 11, with seven legislators sponsoring it.

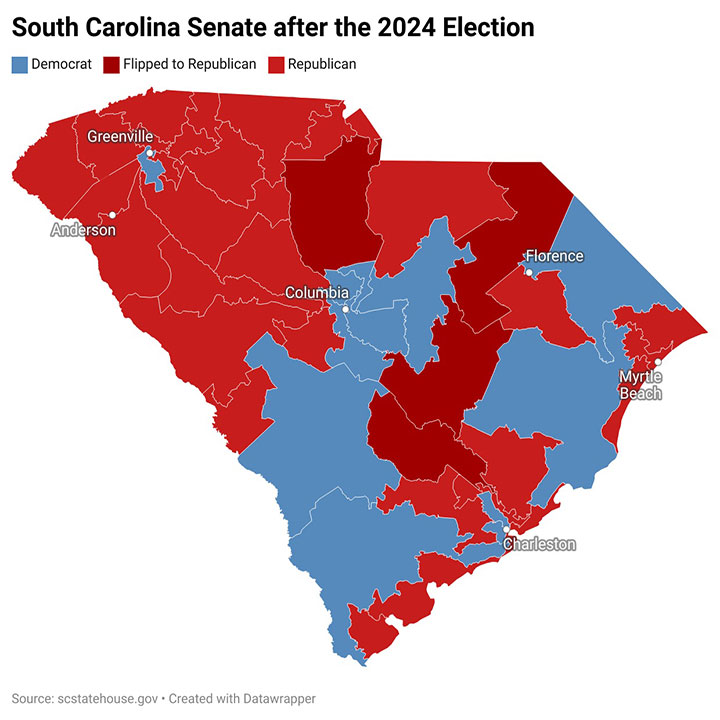

In the 2024 elections, Republicans gained four Senate seats, giving the party two-thirds of the Senate – a supermajority, with 34 seats. They also retained their supermajority in the House.

Vicki Ringer, director of public affairs for Planned Parenthood South Atlantic, said the supermajority creates a clearer path for anti-abortion legislation.

“We’ve been able to delay or stop some of that harmful legislation in the Senate,” Ringer said. “The chances of being able to do that now are pretty slim.”

Stricter abortion laws face challenges from within the legislature as well. Magnuson said House leadership is reluctant to pass any new restrictions.

“I think amongst the leadership, there’s a sense that we need to minimize the issue of abortion and (realize) that it’s not a winning political issue,” Magnuson said. “And so I question whether the issue will be brought up, because I know that the (House) speaker has said that he does not want to deal with abortion.”

Kilmartin also blames an ideological split in the party, saying House Republican leaders are obstructing the passage of stricter abortion laws because they’re sympathetic to liberal causes.

“Until the liberal leadership is out of office, we can’t go anywhere with this because they don’t work with conservatives very well.”

Magnuson said federal leaders, including President-elect Donald Trump, also have become less assertive on their stance toward regulating abortion.

“President Trump has stated that he wants every state to be able to make the laws that they choose,” Magnuson said. “I hope that that means that he will stay out of our conversations and allow for the will of people to take its course here in South Carolina. I know that Trump has said that he does not feel that we should have life-at-conception bills. He feels like even the heartbeat bill went too far. So I disagree with him on that.”

The presidential election results also have made state regulations on abortion even more influential, said Caroline Scott, president of Advocates for Life at University of South Carolina.

“With the Trump-Vance win in the 2024 election, I think that we’re going to see an uptick in pro-life laws being implemented across the country,” she said, “or at least maintaining the removal of federal abortion laws and letting states decide how they want to approach that subject.”

In many states’ elections, voters were able to decide the future of abortion rights at the ballot box.

“I think having the ability to vote on abortion laws and abortion plans in your particular state is how I foresee the country moving forward,” she said.

Holly Gatling, executive director of South Carolina Citizens for Life, said the federal government still has some say in abortion regulation.

“Elections have consequences,” Gatling said. “The federal government can stop funding to abortion businesses like Planned Parenthood. … Even though the regulation of abortion has gone back to the individual state, funding is a federal issue.”

Planned Parenthood receives government funds as part of the Medicaid program, Ringer said, but its status in the program is often contested.

“Every year there is an attempt to kick Planned Parenthood out of the Medicaid program,” Ringer said. “And the courts and the national Medicaid program has said, ‘You can’t kick out qualified providers just because they provide abortions.’”

Kelli Parker, director of communications and marketing for Women’s Rights & Empowerment Network, said the results of the 2024 elections pose an immense challenge for reproductive rights advocates. But the South Carolina group is prepared to continue its fight, even if that means taking a different approach.

“We’re remaining focused on protecting reproductive rights at the state level and pushing for more things like economic justice,” she said. “So, if we’re not going to be able to have abortion access, then we can push for paid parental leave. We can push for universal childcare. We can make sure that women are paid equally.”

The legislature reconvenes Jan. 14.

The South Carolina Supreme Court will hear arguments Feb. 12 regarding the Fetal Heartbeat Act. The court will rule on whether the ban should stay at six weeks or be reduced to nine weeks, which was provided for in a previous bill.

SC women face reproductive healthcare challenges

Expanding abortion laws could exacerbate the issues women in South Carolina already face when seeking reproductive healthcare.

In many places in South Carolina, the landscape of reproductive healthcare is barren.

The state’s lack of reproductive healthcare providers has forced many women to travel across county lines just to see a doctor, Kathryn Luchok said. Luchok is a senior instructor in the Department of Women and Gender Studies at USC.

“We currently in South Carolina have maternity deserts, places where there’s no OB-GYN in a county,” she said. “People have to travel long distances if they’re in rural areas to get the care that they need. And so for a lot of people, there’s no availability for prenatal care and delivery services.”

Planned Parenthood’s Ringer said the threat of criminal penalties under last year’s Fetal Heartbeat Act is driving reproductive healthcare providers away from South Carolina.

“One of our coalition partners, who is an OB-GYN, recently left the state because she didn’t feel like she could practice medicine in a way that aligned with her ethics and values … because doctors are being penalized for basically doing their jobs.”

Deborah Billings, an adjunct assistant professor in USC’s Arnold School of Public Health, said the ban puts healthcare providers in a difficult position.

Billings said there’s a “culture of fear that is being created and will continue to be even stronger.”

“As healthcare providers, you’re kind of going, ‘What can I do? In certain situations, is this going to be interpreted in a certain way?’” she said.

A report from the state’s now-restructured health agency, the Department of Health and Environmental Control, shows that, in 2020, 32.3 women per 100,000 births in the state died from complications of pregnancy or childbirth either while pregnant or six weeks after childbirth.

That is the eighth-highest maternal mortality rate in the nation, according to the report.

Luchok said South Carolina’s lack of accessible maternal healthcare has contributed to its high maternal mortality rate.

“Maternal mortality doesn’t just count for people who are having babies at term,” she said. “It’s also people who have miscarriages, stillbirths, abortions, spontaneous abortions. Those are all things that if something happens to them later – they don’t get the follow-up care that they need – that they might die and that would be counted as maternal mortality.”

The maternal mortality rate for Black women in South Carolina is four times the rate for white women. Parker said it’s an example of something that exacerbates medical disparities between certain communities.

“The lack of access that South Carolinians experience creates barriers that disproportionately impact low-income people, young people, people of color and our citizens who live in rural communities,” she said.

Republicans gained a supermajority in the South Carolina Senate in the 2024 elections. (Graphic by Mollie Naugle/Carolina News & Reporter)

Some S.C. state legislators want to enact stricter abortion laws. (Photo by Mollie Naugle/Carolina News & Reporter)

State statistics show the disparity in maternal mortality rates between white women and women of color. (Graphic by South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control/Carolina News & Reporter)

In many states, voters determine the future of state abortion laws at the ballot box. (Photo by Mollie Naugle/Carolina News & Reporter)