A charging station sits in a parking lot not far from the Governor’s Mansion in downtown Columbia. The station is one of about 15 stations in the Columbia area. (Photos by Stephen Pastis)

Kevin Gray, a longtime Columbia resident, writer and activist, co-owns a BBQ restaurant with something few places in Columbia offer — electric charging stations.

Railroad BBQ, which sits across from the Richland County Administration Building on Hampton Street, is a repurposed gas station. The charging stations are part of a Tesla program, which installs chargers for free, and the owners liked how the stations keep the site’s fuel theme. The stations are open to anyone free of charge, but Gray does suggest coming in and trying the food after charging, he said.

“It’s a draw to come in,” he said. “And for us, it leads the way for folks in the city with businesses like this to say maybe we should do it, too.”

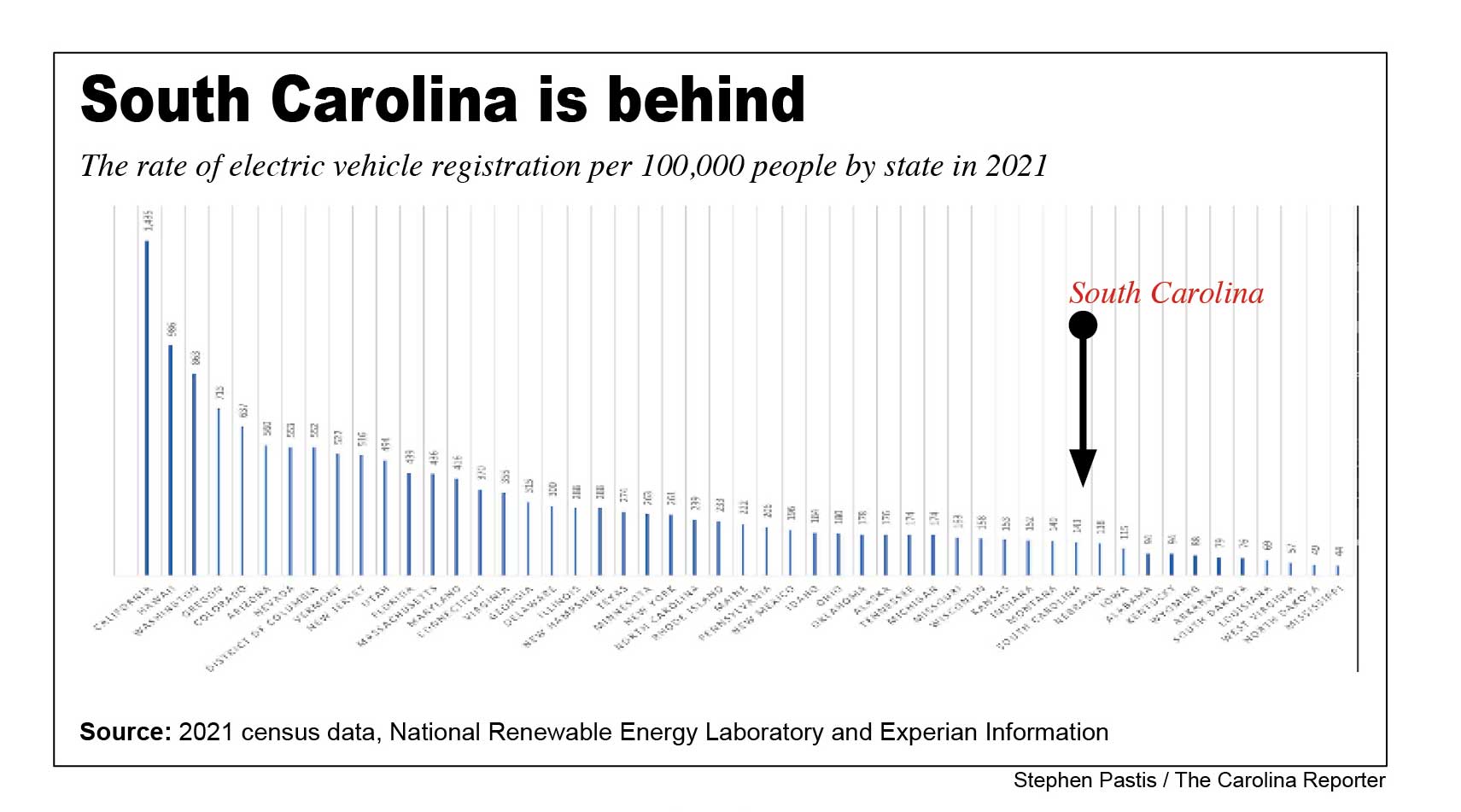

Gray speaks to a broader issue in South Carolina: The state lags behind most of the country in electric vehicle ownership and in building public charging stations. While the number of EVs has nearly doubled each year over the past four years, they comprised just over 0.15% of all registered vehicles in the state in 2021.

The lag in moving to electric in the state is multifold, according to experts.

LACK OF GOVERNMENT INCENTIVES, MANDATES

Nothing’s happening quickly.

William Mustain, a professor of chemical engineering at the University of South Carolina who studies electrochemical batteries, doesn’t see a shift toward electric anytime soon.

“There are not enough incentives now to drive people to buy electric vehicles overall,” Mustain said. “That’s what (the low interest) means to me.”

State government also isn’t making policy that would require a shift to EVs. California, by contrast, has banned all gas-only vehicles starting in 2035.

“For a state like South Carolina to hit full EV penetration — unless the federal government steps in and changes it — I think we’re talking well past 2050,” Mustain said.

The state has seen an almost 2000% increase in electric vehicles since 2014. But the overall numbers are comparatively small. In 2014, there were 357 EVs registered in the state. In 2021, there were fewer than 7,500, according to Experian Information Solutions and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

The 2021 numbers rank South Carolina as having the 10th-lowest number of EV registrations.

Tamara Sheldon, an economics professor at USC’s Darla Moore School of Business, studies EV policy and consumer choice.

“The EV market has historically been really dominated by higher-income consumers,” Sheldon said. “It’s been shown that the majority of financial incentives out there are going to people who are high income and aren’t necessarily buying EVs because of the incentive.”

The few incentives that exist in South Carolina are for government or non-profit entities — none exist for individual buyers. One consumer incentive that existed, a hybrid vehicle incentive plan, expired in 2017.

The 2022 Nissan Leaf — which Mustain said is one of the cheapest electric vehicles — is a small hatchback. It has a shorter driving range than other cars — around 150 miles — and costs $28,000 for the base model, according to Nissan. The full-feature model runs more than $37,000. The Nissan Kicks, a fuel-powered car of similar size, begins at just over $20,000.

Nationally, Congress in August passed President Biden’s plan to invest in emissions reductions, the largest investment in climate and energy initiatives in U.S. history. The Inflation Reduction Act puts the country on track to have a net-zero economy by 2050.

Nevertheless, Sheldon doesn’t think the tax credits included in the plan are enough to make EVs affordable to most.

Even Mustain, who calls himself a “battery person,” doesn’t think the long-term cost for buying electric at this point makes sense for most, including himself.

LACK OF INFRASTRUCTURE

Ben Johnson is a South Carolina native and Columbia-based real estate agent who has owned a Tesla since 2019. He doesn’t think he will ever drive anything else.

“The worst part of owning a Tesla for me right now is that my husband’s insisting on getting one, too,” Johnson said, laughing.

Another issue is that superchargers — a Tesla charging technology that charges much faster than standard chargers — are hard to find, Johnson said.

Still, he has a charging station at home, so charging is less of a problem for him, he said.

But when he visits his parents in Anderson or goes on other long trips, he has to plan for it. In traveling around the state, he has seen how difficult it can be to find the next energy source in rural areas or away from major roadways, he said.

He doesn’t think it would be feasible to own an electric vehicle in a rural area in the state.

That’s an issue.

South Carolina is largely a rural state. Rural areas have different needs than urban areas, with regard to driving times and vehicle necessities, while access to charging stations can be non-existent, Mustain said.

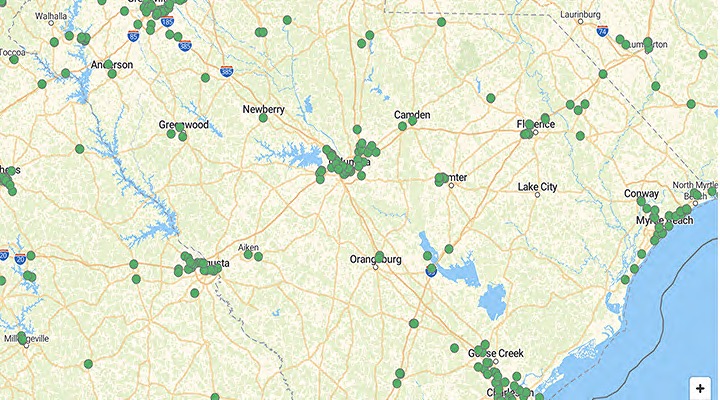

There has been a large increase in electric fueling stations statewide since their introduction. As of October 2022, 350 public charging stations exist in the state, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. That compares to 3,831 gasoline stations, according to the S.C. Department of Agriculture.

North Carolina, in contrast, has 1,004 public charging stations.

The majority of EVs in South Carolina were registered in cities in 2021. Charleston County had the most, followed by Greenville, York and Richland counties, according to Experian Information Solutions and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

Adel Nasiri is an electrical engineering professor at USC who is developing a charging station company. He said infrastructure is costly and complicated to implement and will require extensive efforts from energy providers, city planners and state government alike.

Nonetheless, he is optimistic, saying that during his 20 years in the field, he has been impressed with how quickly the United States has moved.

“The growth in electric vehicle penetration, deployment and the prospect has been much faster than anticipated,” Nasiri said. “It was not supposed to be this fast as of two years ago. And suddenly comes this almost avalanche, from two years ago, that every manufacturer wants to do electric vehicles.”

Businesses such as ABB E-mobility, a Swiss electric vehicle charging station manufacturer, are moving stateside. ABB E-mobility announced in September a $400 million investment to begin production in West Columbia, according to a news release.

And the German-based BMW, whose only U.S. manufacturing plant is in South Carolina, announced this month it is investing nearly $1.7 billion dollars to begin the shift, according to the Associated Press.

MOVING FORWARD

Even if EVs were more accessible and the infrastructure materialized, there is also a potential for the cars to actually increase greenhouse gas emissions.

In states that burn coal for electricity, an increase in electricity usage could mean more emissions.

“The one thing that South Carolina has going for it is that we have fairly clean electricity here because we have a lot of nuclear powered electricity, which doesn’t have any carbon emissions,” Sheldon said. “So we are — you know, in terms of realizing environmental benefits from EVs — we’re on the better end of that spectrum.”

Sara Bazemore is the director of the state’s energy office, a federally funded state agency that works to promote energy efficiency, renewable energy and clean transportation.

“One thing that I enjoy is being able to talk to folks who might immediately want to scoff at or dismiss South Carolina as not really doing a lot in the energy sector … because we don’t have those mandated goals that have been established,” Bazemore said. “But we have a lot going on, and we are making a difference and we are making a lot of changes in renewable energy adoption and clean transportation.”

Starting in 2020, the agency worked with a group of 350 stakeholders to create a roadmap to electrification. In May 2021, Gov. Henry McMaster created a joint committee to look at the recommendations of the report.

In October, he also issued an executive order outlining the state’s comprehensive efforts to embrace electric vehicle-related resources and infrastructure, with a focus on highways and rural areas.

Bazemore said it may be a while before efforts are noticeable but education and awareness is growing.

“There is a recognition that it’s coming, it’s happening,” Bazemore said. “So whether you like it or not, electric vehicles are becoming more prevalent and the need for the charging infrastructure is growing as well.”

A Tesla charges at RailRoad BBQ for free. Tesla cars and chargers are becoming more common in the area, restaurant owner Kevin Gray said.

A quirky sign from Tesla hangs outside the RailRoad BBQ restaurant, directing cars to charging stations.

S.C. electric vehicle charging stations tend to be congregated in cities, while rural areas often have no public stations. (Map from the U.S. Department of Energy)