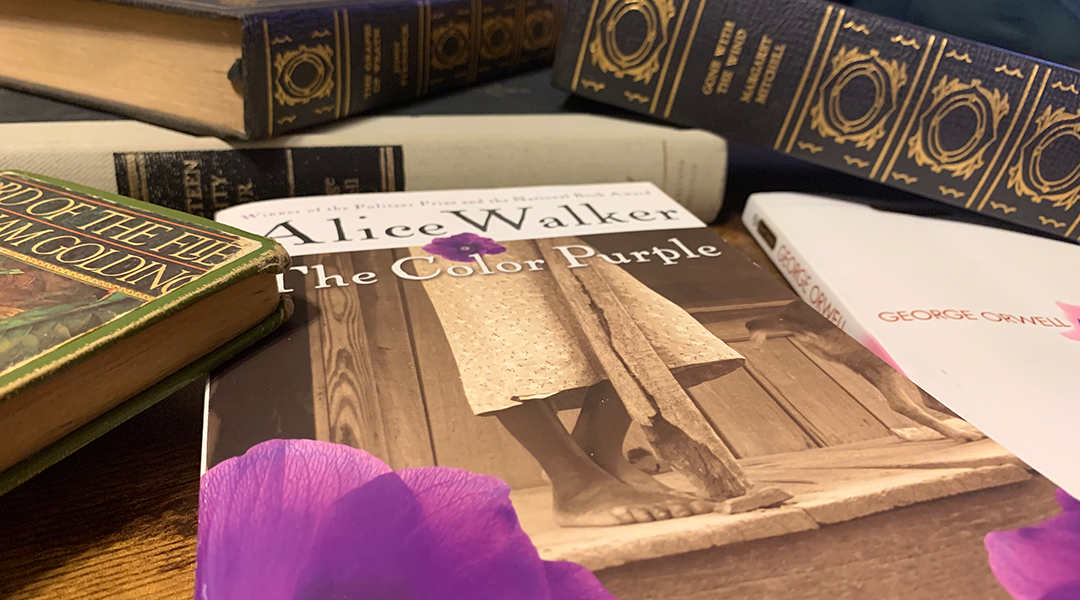

Classics and books with content addressing diverse communities are frequently challenged across the United States. (Photo illustration by Bee Brawley)

Lexington-Richland School District 5 temporarily removed “Black is a Rainbow Color” from its schools’ libraries this October after the book was formally challenged.

The book by author Angela Joy was challenged by a parent in the district, whose child attends Lake Murray Elementary. The parent filed a formal complaint with the school Oct. 20. The parent wrote that if students used the material “some phrases may be confusing and hurtful to other students” and that it “could foster low self-esteem, social isolation, and show that love is only skin-deep.”

The district’s complaint form asked that the parent cite specific material. In response, the parent wrote that the book contained “’Black Lives Matter’ imagery — divisive, political propaganda not seen as historical.”

Dianne Johnson-Feelings, who researches children’s literature at the University of South Carolina, finds the challenge and others like it “frightening.”

“I don’t doubt that they’re sincere, but they don’t have the context,” Johnson-Feelings said. “… They don’t know the history of the United States. They don’t know the history of American literature.”

The challenge to “Black is a Rainbow Color” is just one example of rising book challenges across the nation, as parents, some from conservative groups, object to material found in school libraries. In addition to Lex-Rich 5, Beaufort County Schools had one parent ask that nearly 100 books be removed.

The American Library Association, or the ALA, tracks how often books are challenged. In 2021, the ALA reported 729 attempts to ban or restrict books — the highest documented number since the group began compiling data more than 20 years ago. As of September, the group reported 681 attempts this year.

The ALA also monitors the content of challenged books. Books that are frequently challenged contain content about diverse populations, such as Black, LGBTQ+ or other minority groups. “Black is a Rainbow Color” is one of many examples.

In the complaint form on the Lex-Rich 5 website, the parent objected to the use of the phrase “Black are dreams and raisins … left out in the sun to die.” The line is a reference to “A Raisin in the Sun,” a play written by Lorraine Hansberry in 1959 that draws from a work by Langston Hughes, a famous Black poet.

The complaint shows that the American education system has failed to teach students about Black history, Johnson-Feelings said.

“That’s the main problem — that we don’t know our own history,” she said. “We know the history of those who are in power, who have been able to tell their history and leave out other histories. That’s why it’s so frightening, that there are all of these efforts to restrict what our children read because that dumps us back into a national state of ignorance.”

The book was ultimately returned to library shelves in the Irmo-Chapin district after a review committee voted unanimously that “the book is acceptable and appropriate for School District 5 libraries,” according to district spokesperson Laura McElveen. District officials declined to comment further to The Carolina News & Reporter.

Challenged books in other areas have not been returned to shelves.

Still, ensuring diversity in literature is a key aspect of what librarians do, according to Kathy Lester, the president of the American Association of School Librarians, a division of the ALA, told The Carolina News & Reporter.

“When students can feel engaged in their reading and feel connected to that reading, then they’re likely to read more, which builds that student engagement and therefore student achievement,” Lester said.

Johnson-Feelings said another factor is at play.

“Everybody needs to read about the experiences of everybody else,” she said. “So Black children’s literature is not just for Black kids, right?”

Other critics are concerned that books can be removed from a library’s circulation while a review is pending.

“Public libraries generally have the policy that the book should remain on the shelf while it’s being reviewed, while a lot of school boards have adopted a policy that a book is pulled when the review is called for,” said Josh Malkin, legislative and policy advocate at the ACLU. “But the problem that this leads to is that in Beaufort, someone asked that 97 books be reviewed.”

The challenges in Beaufort began in late October, when 97 books were temporarily removed following a complaint.

In November, Ivie Szalai, a district parent, separately emailed the district a list of 96 books she wanted removed.

“The idea that one person — who may or may not be a parent, it doesn’t really matter — can single-handedly take 97 books out of school circulation is terrifying,” Malkin said. “This banning undermines and challenges the competence and professionalism of our librarians. It also suggests that some parents or some residents should have the authority to control what every child in South Carolina is able to read.”

But those doing the challenging say the issue isn’t about diversity but the safety of children.

Szalai is a member of the national group Moms for Liberty, according to The (Charleston) Post and Courier. Moms for Liberty is a nonprofit organization that challenges books if it believes they violate state or federal law, according to Tiffany Justice, who co-founded the Florida-based group.

“It’s always been about, you know, aligning with state statute and federal obscenity laws, ensuring that our children are safe when they’re at school and that the materials that it suggested that they engage with are age-appropriate,” Justice told The Carolina News & Reporter.

The organization was formed in January 2021 after the co-founders “witnessed how short-sighted and destructive policies directly hurt children and families,” according to its website.

Moms For Liberty has hundreds of chapters. Other books it has challenged are “Ruby Bridges Goes to School: My True Story” and “Martin Luther King Jr. and the March on Washington,” according to a formal complaint filed with the Tennessee Department of Education.

The Florida chapter of the organization challenged more than 150 books in November of last year, including “The Color Purple” by Alice Walker. Five of the books were permanently banned, according to Newsweek magazine.

According to Justice, Moms for Liberty has no intention of banning books outright, but rather removing books from libraries that are age-inappropriate or run afoul of community standards.

“There has been a lot that has been said about book banning — that somehow moms want to ban books — and I want to be clear and say that is not the case,” Justice said. “We have a very clear stance: write the book, publish the book, print the book, sell the book, put the book in the public library, if the taxpayers in your community want to support the purchase of that book.”

Justice suggested that books be limited in the same way that films and video games are, by rating.

“They have different video games that have ratings so that parents can understand what the content is in the video game,” Justice said. “Books are no different.”

Malkin, whose job involves monitoring when books are challenged across the state, said that the idea that books do not have rating systems is wrong.

“There are sections (of libraries) where you need parental consent for taking out a book,” he said. “So every time that a book is placed in a library’s shelves, they’re going through their rating system.”

Librarians are advised to consider factors such as age when selecting books, according to the ALA. They are also advised to select books that represent different viewpoints on controversial issues and provide a global perspective while promoting diversity.

In Beaufort, no decision has been made on the status of the books in question.

On Sunday, Dec. 11, Beaufort’s Pat Conroy Literary Center is hosting a community forum on book challenges. Malkin is one of four scheduled panelists.