Brooklyn and her mom ventured to the drum kit, where they hit the drum to the beat of the music being played by the instructors. More children came to join when they heard what was going on. (Photos by Emily Okon)

The faint, sweet music of a ukulele can be heard from across the parking lot in the chill of the early morning. No one would expect that a rustic building on the banks of the Congaree River would be home to the soft sounds of infant laughter and music.

This rustic space is home to Tempo Music and Arts.

In September 2020, Kim Donovan, a mother of two, began teaching parents new ways to interact with their young children musically when she opened the doors to her music school. Parents and young kids learn outside in a socially distanced environment.

The idea behind the school – and behind music instruction, even in college? To introduce music to infants and toddlers. And, by teaching parents to take into account how a child responds to music, they can learn to encourage noises that promote life-long benefits.

“Just knowing that your kid is making sounds for a reason can change how we respond,” said Donovan, who previously taught music education in an elementary school for eight years.

Classes are held on the patio in the greenery that surrounds the building off Senate Street. The only times they venture inside is when the weather gets too cold. Not only are they outside for the view, but by holding classes outdoors, they are preventing the spread of COVID to the immune system of young infants.

Before Tempo, Donovan was Lexington School District 2’s teacher of the year in 2018. When the world retreated indoors because of the pandemic, she opened her school, wanting to focus on hands-on learning in a safe environment.

It’s not just idle babbling

Being outdoors, encouraging parents and children to soak up Vitamin D, is only part of what makes Tempo unique.

Tempo teaches parents how to respond to the sounds their children make. Learning the reasons behind the babble is a core philosophy that parents are taught when they attend a class.

“Babbling” is the scientific terminology for the consonant-vowel sounds that children make in early development.

This babble typically doesn’t mean anything to our ears. But the sounds are a crucial stepping stone to communication development.

“We’re teaching them how to interpret their child’s responses,” Donovan said “It’s about listening to the pitch of the fussing and figuring out how that relates to the sound. Are they trying to respond musically versus just being uncomfortable?”

It’s common for children to make wacky noises.

But Donovan stresses that children’s babbling is actually very important for young infants as they are learning how to speak.

A method to the music

Wendy Valerio is a professor of music education at the University of South Carolina.

Her classes teach students in teacher training how to facilitate musical communication between young children and their caregivers.

In Valerio’s music education course, her students are required to gain experience through instructing at Tempo or at the USC Music Play classes that are distinctly similar to the courses taught at Tempo.

“There’s no better teacher than experience,” Valerio said.

During her undergraduate studies at USC, Donovan nurtured a relationship with that professor, Valerio, and has used many of her teachings in both public education and now at Tempo.

While Donovan still attends each class and participates as a mother herself, she tends to sit on the sidelines as Valerio’s graduate students take the role of instructor.

Music Play at USC uses the same practice to allow college students to gain more hands-on learning experience under Valerio’s guidance.

Not just for the musical at heart

Music education is not just for future musicians.

Music is beneficial to everyone. Little research has been done that directly documents lasting health benefits. But musical practices have been tied to lowering blood pressure, deep breathing practice and cognitive awareness, Valerio said.

Music learning operates in a similar way to learning a language. Children expand their listening vocabulary when listening to music. They even can begin to find their own internal tempo. Learning to recognize rhythms and tempos early in children’s development can make dancing and musicianship much easier to learn later.

“Kids learn language by being surrounded by it and also by observing adults and how they use language,” Valerio said. “Subconsciously they’ll start learning the language.”

Tempo and USC are not the only ones inspiring music in young kids. The Center for Dance Education is also inciting musical ability through its classes for dance and movement.

Shannon Chapman has been teaching dance for more than 15 years. After attaining her master’s degree in dance education from New York University, Chapman settled in Columbia as her daughter was born.

She teaches two ballet classes and has recently started a mommy-and-me style class for early childhood movement. Her classes teach parents how to move with their kids in ways that can lead to life-long benefits. The classes help children find their internal tempo and rhythm while increasing their fine- and gross-motor skills.

Benefits beyond music and movement

The human body has two types of motor skills, fine and gross.

Fine motor skills are the movements in smaller muscles, such as the hands. Gross motor skills are the use of larger muscles in movement, such as walking, running and crawling.

Her students polish their motor skills by focusing on what muscles need to move to repeat the movements they watch her do.

Classes give students “an entry point into accessing not only their fine and gross motor skills and dynamics,” Chapman said. “As a parent, you have movement patterns that are ingrained into you. To have access to another adult or teacher that has different movement patterns allows the child to see those different ways of moving.”

Chapman not only teaches her own classes but attends Tempo Music and Arts with her daughter, Adeline.

Since she started attending in the fall of 2022, she has seen her child become more comfortable in class, and begin engaging with the different ways to make sounds.

The classes also had an impact on Chapman’s social life.

“Early motherhood can be a very lonely place, and to have a safe space for Addy to see other kids and me to see other adults is definitely very beneficial for everyone’s happiness,” Chapman said.

Donovan knows Tempo has grown into an outdoors community of sorts for parents and children.

“We now have this community of parents that love being outside,” Donovan said. “We all have kids the same age, and we appreciate the same things. I go to birthday parties, and they’re all my Tempo parents because we’ve all stuck together. That’s been something I never planned for. But it’s been the best part of this.”

Jack Ryan holds up his rhythm sticks to show how he makes music while his mom tries to gain his attention.

Ashley Cobb, a first-year graduate student at the University of South Carolina, dances with moms as they sing a song about airplanes. The unplanned performance was inspired by the sounds of an airplane over head.

Caroline plays with cut pieces of a pool noodle, turning them into musical instruments called scrappers. After much thought, she chose to use the concrete ground and her scrappers as a way to make noise.

Noa, Lucy and Marielle, from left to right, mirror their instructor as she leads them through the basic pointe positions at the Center for Dance Education.

Wendy Valerio of USC embraces multiple methods of teaching but truly believes learning comes from experience.

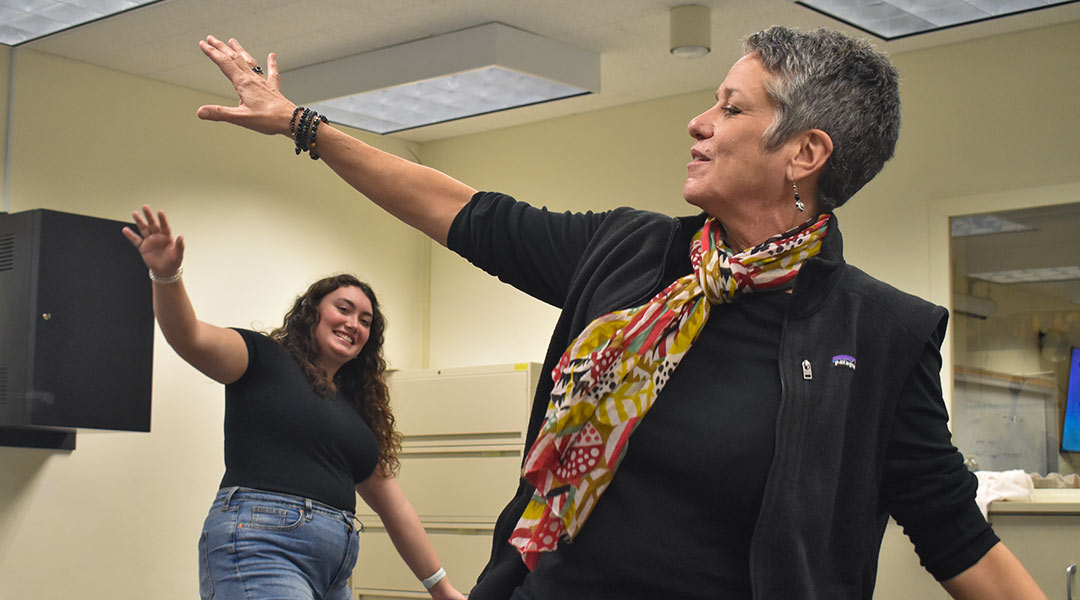

Valerio and undergraduate student Hope Zinkann practice hands-on learning. They’re pretending to be on a surfboard while making mouth sounds to match tempo with the rest of the class.

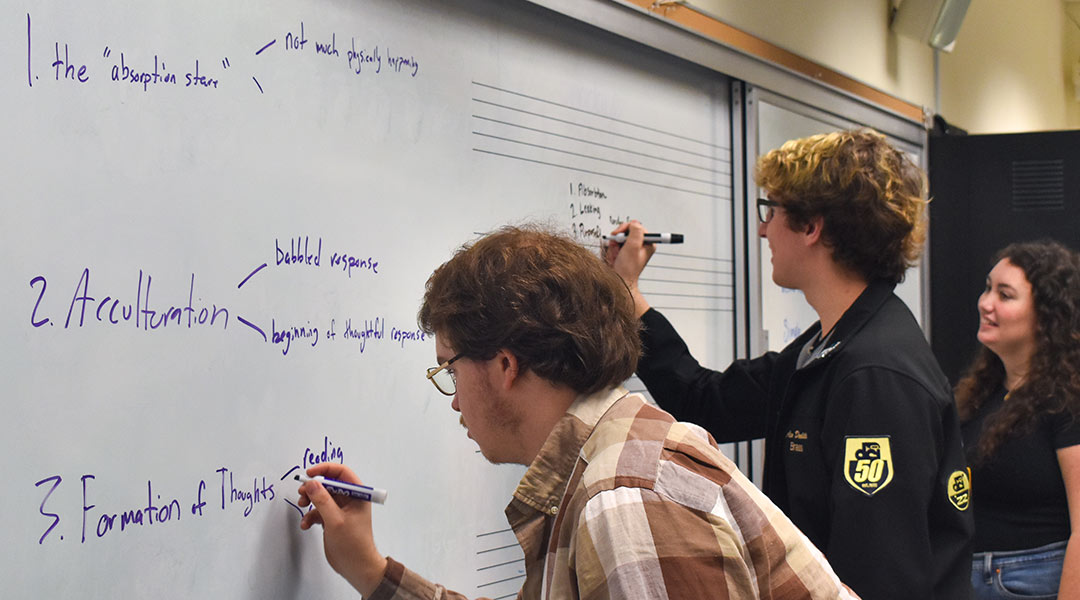

Adam Dinkins, Alex Doolittle and Hope Zinkann test their knowledge of the stages of preparatory audiation. This process is the term for musical thinking in children who have not passed the stage of babbling.