Steve Martin has been a volunteer at the Hooves, Hearts & Hope Equine Rescue and Sanctuary for two years. He has developed relationships with many of the organization’s horses and is helping to rehabilitate four recent rescues.

Four brown horses stand together at a Swansea farm edged in sloping oaks and pines.

They never learned to eat apples or carrots. Slowly, they’re discovering what horse treats are. They tremble beneath human touch, if they allow touch at all.

“They’re just absolutely scared,” said Danielle Fowlston, owner and president of the nonprofit Hooves, Hearts & Hope Equine Rescue and Sanctuary.

Diamond, Stormy, Laney and Mocha were rescued by the Orangeburg Animal Control last summer from an animal cruelty situation. They recently found a place to rest and recover with Hooves, Hearts & Hope.

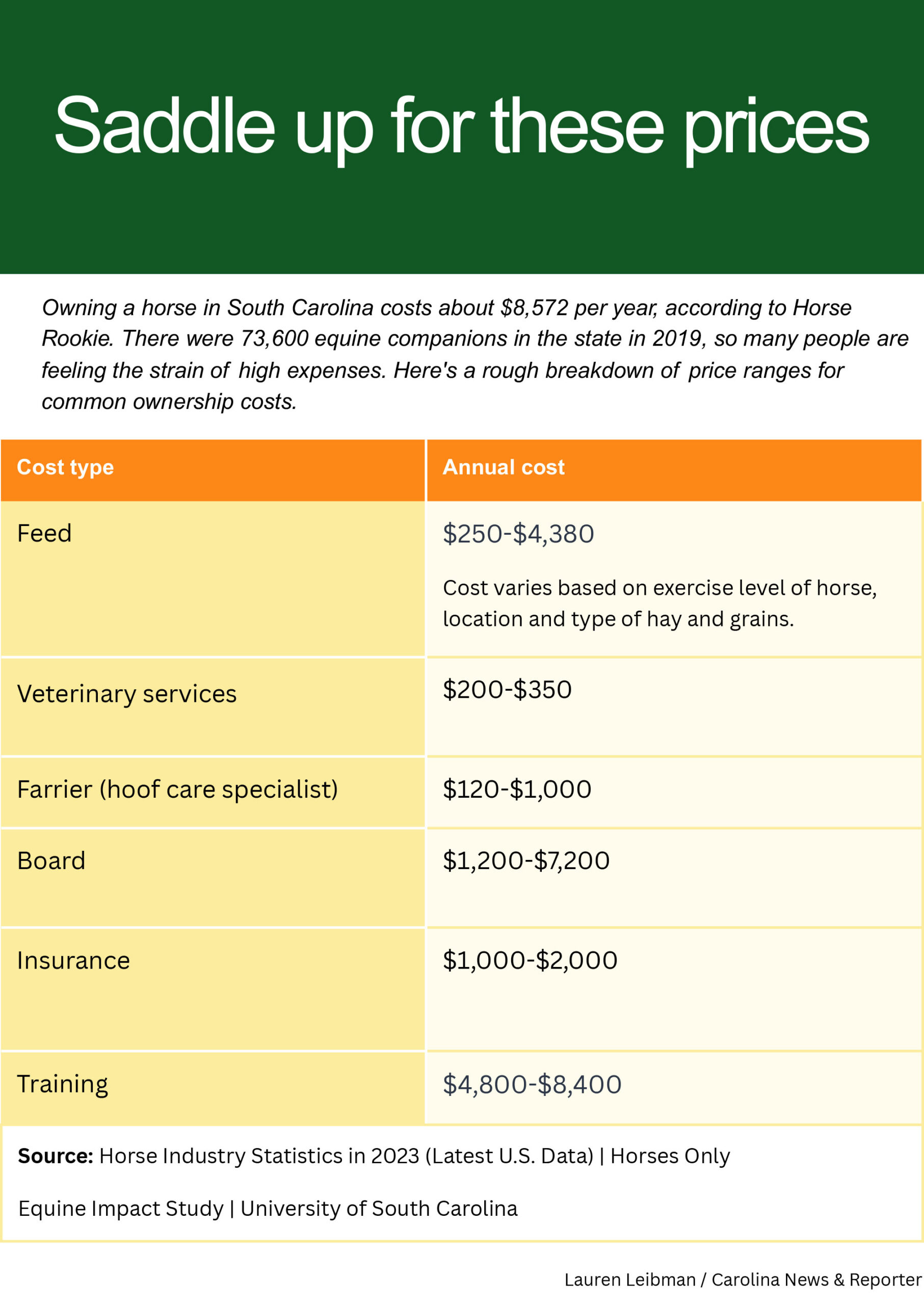

But caring for the rescue horses hasn’t been cheap for the nonprofit. And horse ownership in general has become increasingly costly over the past few years. Rising costs and a lack of resources have made it difficult for some S.C. owners to continue caring for their horses, whether on their own property or at a boarding facility.

The costs have forced some to confront the difficult reality that they can no longer afford to keep their animal.

And it means Hooves, Hearts & Hope has received more calls than ever from owners looking to surrender their horses, Fowlston said.

The rescue even has been forced to turn people away because it doesn’t have the resources to look after more than the 20 horses it already has.

Animals that aren’t surrendered to responsible owners or rescue organizations can sometimes fall victim to abuse and neglect.

“That’s how horses end up in unfortunate situations,” said Camryn Lubner, a life-long horse owner and member of the University of South Carolina’s equestrian club team. “Because people have to give them up, and they end up in the wrong hands.”

The high cost of ownership

The price of horse feed has increased dramatically since the onset of the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The price of hay has gone up 25%, according to Teresa MacFawn, owner of the boarding and training facility Three Fox Farms in Blythewood. Grain prices have increased by roughly 29%, MacFawn said.

Angela MacFawn said it’s high food prices that sometimes lead to animals being neglected.

“I don’t think people have bad intentions,” Angela MacFawn said. “It’s just they get them, they love them, but they can’t afford to feed them what they need to.”

The cost of insurance, veterinarian services, medications and other day-to-day expenses costs also have gone up.

Some boarding facilities have raised their prices to account for that.

Lubner, the equestrian team member, grew up on a farm in New Jersey, where her family runs a boarding facility.

The farm has historically charged just enough to cover costs. But recently it changed its pricing to continue to break even.

“We feel terrible having to raise prices this much, but we’re losing money if we keep it this way,” Lubner said.

Three Fox Farms also has been forced to raise its prices.

The cost of boarding is a large part of the financial burden for some horse owners. Higher prices put an even tighter strain on owners who can’t house their own animals.

Lack of vets and other barriers

Barriers to accessing health services also hinder the ability of horse owners to properly care for their animals.

Holly Hallman, Lexington County’s livestock and poultry investigator, is responsible for conducting welfare visits on livestock animals such as horses, pigs, goats and cattle and for enforcing local animal ordinances. She is the only person in the state to hold such a position.

One of Hallman’s biggest challenges is persuading owners to call a veterinarian when their animals are sick or injured.

Even when owners are willing, it isn’t always easy to get medical care for large animals, Hallman said.

It sometimes takes days for a vet to become available. That’s especially true in places like Lexington County, where the closest large animal vet is in Aiken.

“With dogs you can walk into a vet and they’ll take you right then,” Hallman said. “But you can’t just roll up to the vet with a horse.”

South Carolina, like the rest of the country, is still in the throes of a serious veterinarian shortage, said Dawn Wilkson of the Humane Society of South Carolina.

The shortage has extended to the equine community.

Only about 1.3% of veterinary graduates go into equine medicine, according to the American Veterinary Medical Association. And 50% of them become small-animal vets or leave the veterinarian practice entirely after five years.

Clemson University hopes to address that by adding a veterinary school, the state’s first.

A shortage of experienced farriers also can be a barrier, Hallman said. Farriers are specialists in horse hoof care. They are responsible for shoeing horses, an important part of routine horse maintenance.

Lubner has noticed a challenge in finding qualified vets and farriers, too.

“I think the ones that are worth your while are few and far between,” she said.

Education and dedication are key

Ensuring that horses remain in stable, nurturing environments comes down to owner education, said Wilkinson, director of the Humane Society of South Carolina.

Mistreatment most commonly results from a lack of resources and knowledge of how to care for animals.

Many small animal shelters offer education and training programs. But information for horse owners seem to be less available.

Education is especially important now because of an increase in animal neglect cases, Wilkinson said.

Rescue organizations such as Hooves, Hearts & Hope are instrumental in responding to the increase by providing homes and care for surrendered or mistreated animals, Wilkinson said.

The staff at Hooves, Hearts & Hope is working diligently to care for all their horses and, in particular, to rehabilitate the group rescued from Orangeburg last summer.

Fowlston said physically the horses need food. But they require the volunteers’ dedication and affection more than anything.

Leon Mack is a volunteer referred to as the rescue’s “genuine cowboy.” He wears a white hat with a long feather and hugs the horses close to his chest as he makes his rounds through the pastures.

He talked about his love for the volunteer work he does and the devotion horses have to their owners, a stark contrast to the stories of neglect and mistreatment.

“You want to see loyalty, look at these horses,” Mack said, stroking one gently on the neck. “All they know is loyalty.”

But working with the horses can be emotionally stressful for the volunteers.

Steve Martin has been with Hearts, Hooves &Hope longer than any other volunteer. He didn’t know anything about horses before joining the organization two years ago, after the death of the farm’s original founder, Linda Leech.

Martin has since formed deep connections to the horses, even adopting two of them as his own.

So it was difficult for him when he learned that Patty, a fifth horse seized in the Orangeburg animal cruelty case, had to be put down. Before coming to the sanctuary, Patty had developed abscesses in her back hooves and had grown an extra bone. Her injuries were too severe to be corrected.

Martin said the rescue gave Patty the best year of her life, even if they couldn’t save her.

“I have learned a lot since I’ve been here messing with these horses,” Martin said, his eyes moist with tears. “But learning to deal with having to say goodbye? Yeah, that still tears me up.”

Skylar Fowlston, daughter of organization president Danielle Fowlston, stands with a rescue horse named Stormy. Skylar is the only person who has been able to approach all the Orangeburg rescue horses.

Leon Mack volunteers at the rescue full time. He finds peace in working with the horses and enjoys posting about them on social media.

Dollar is a sanctuary horse that was rescued after his owner, a psychologist, was killed by one of his patients. The patient hit Dollar in the knees with a 2×4, leaving him with a permanent limp. Dollar is one of the most social horses at the sanctuary.