Monarch butterflies, attracted by the state’s native milkweed plants, pass through South Carolina on their migration route. (Photo courtesy of Christine Regan/Carolina News & Reporter)

South Carolina is aflutter with swarms of orange monarch butterflies as they migrate south for the winter each fall.

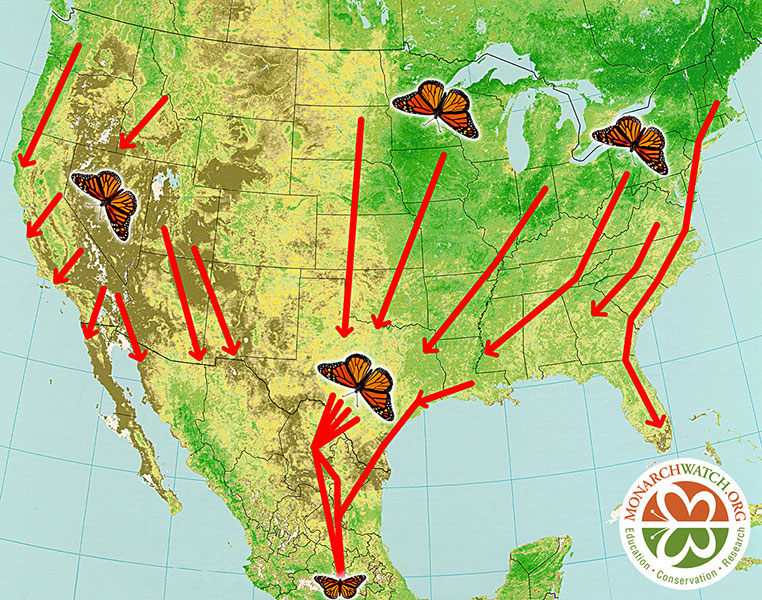

While the butterflies are native to a range of regions across the globe, North American monarchs are the only monarchs that migrate and among the few that migrate at all. They are born in the forests of Mexico, where they mate and raise a new generation of monarchs that make their way north, traveling as far as Canada.

On their way, the butterflies pass through the East Coast, including South Carolina. Arlene Marturano, a landscape analysis coordinator with the Environmental Education Association of South Carolina, said the state’s climate helps make it an ideal place for butterflies to pass through.

“It’s similar to the bird migration route,” she said. “It’s probably the Atlantic Flyway for birds. But it seems to be also the Atlantic Flyway for butterflies. And it’s probably due to several things, the wind and the temperatures.”

Dr. Michael Kendrick works with the state Department of Natural Resources observing the monarchs’ behavior as they pass through South Carolina. He said the region’s climate, especially in coastal areas, has led to monarchs staying there through the winter.

“Some of those monarchs in the fall end up staying and overwintering on our barrier islands and sea islands along our coast,” he said. “That’s where temperatures are sort of moderated a bit by the relatively warm ocean water. And so that allows them to sort of stay along the coast and overwinter in those habitats.”

The butterflies are also attracted to the aquatic milkweed native to South Carolina’s swamps and wetlands, Kendrick said. Milkweed is the only plant that monarch butterflies can lay their eggs on and monarch caterpillars can eat once the eggs hatch.

While the monarchs do gravitate toward South Carolina’s coast to access milkweed, Kendrick said they have been observed in the Midlands as well.

“We have done some work in the Congaree River watershed showing that monarchs are certainly using the aquatic milkweed in some of those watersheds,” he said. “We haven’t done as much research in some of the watersheds that are closer to the Midlands there. But I wouldn’t be surprised to find Monarchs using those habitats as well.”

Efforts to make the Midlands a more habitable place for the monarchs are increasing, though. Monarch Watch, an international organization that tracks the butterflies’ fall migration, oversees the Monarch Waystation Program, which promotes creating monarch-friendly spaces along the migration path.

The Sustainable Carolina Garden at the University of South Carolina plants milkweed as part of that project. The project helps make the journey easier for the butterflies, said Maddie Essex, operations and reporting care coordinator for Sustainable Carolina.

“Historically, the Southeast, this stretch of the country — but specifically the Midlands in South Carolina — has often served as a crucial rest stop or corridor for migrating butterflies like the monarch,” Essex said. “Having a waystation is essentially providing them with nectar and other sources and a habitat. It’s almost like a pit stop.”

Gardeners have to be careful about the type of milkweed they plant and how they care for it, though. Marturano said certain non-native milkweed, such as Tropical Milkweed from Brazil, can do more harm than good to the butterflies.

“(Tropical Milkweed) grows really high and fast and stays viable into December,” she said. “When people wanted to start saving the monarch, they would ask for something quick. … It carries a protozoan parasite that kills the monarch in any stage — it can kill it as an egg, it can kill it as a caterpillar, as a pupa or as a butterfly.”

Pesticide use can also be dangerous for the butterflies and the milkweed population as well as other pollinators and the plants they need to survive. Essex said Sustainable Carolina does not use any chemical sprays in its garden as part of its efforts to maintain it as a monarch waystation.

“Milkweeds and nectar sources are declining due to development and the use of herbicides in farming, which is one of the reasons why we joined this project a couple years ago,” she said. “We’re very aware of that, and we’re trying to combat it to raise a little bit of awareness.”

Kendrick said creating monarch-friendly spaces can be beneficial for other aspects of the environment, too.

“Monarchs themselves have inherent value, but they’re also representatives of broader healthy ecosystems and environments,” Kendrick said. “So if we can protect and conserve these landscapes for monarchs, we’re not just protecting and conserving monarchs. We’re also supporting the other organisms that are important to those environments.”

As the butterflies make their journey north for the winter, providing them with a safe place to land can help ensure a successful migration. Essex said being able to give the butterflies that habitat is one of the most rewarding parts of making the garden monarch-friendly.

“It’s a sign that you’re doing something right, that something is thriving in your garden,” she said. “It’s nice to know they’re landing in your space. You’re providing them nutrition. You’re providing them a safe space.”

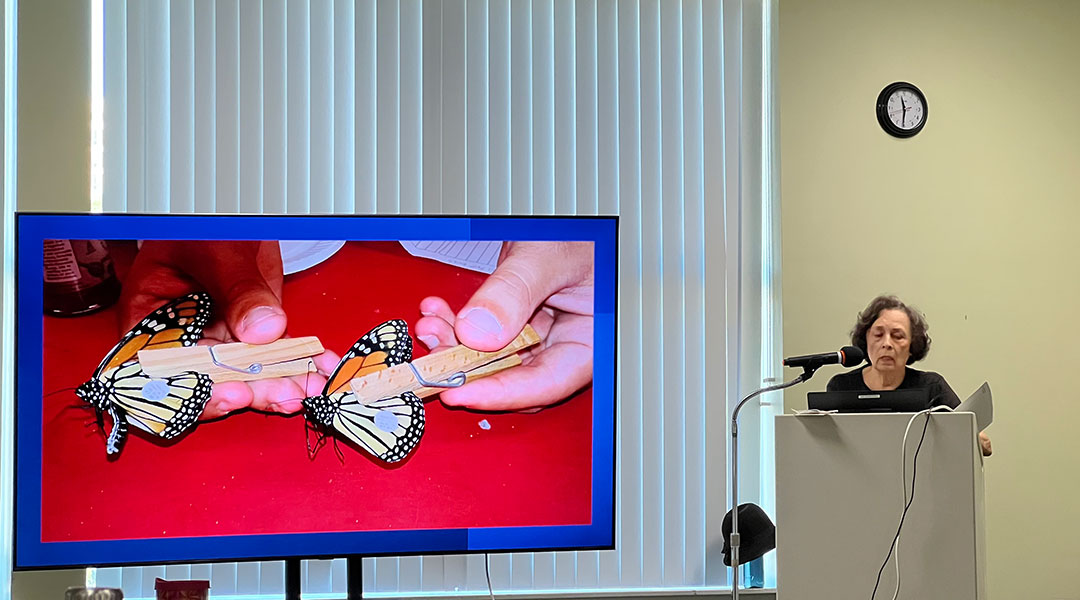

Monarch Watch, an organization that tracks monarchs’ migration, oversees the Monarch Waystation Program, which promotes the creation of monarch-friendly spaces. (Photo courtesy of Maddie Essex/Carolina News & Reporter)

Monarch butterflies in North America are the only butterflies on the continent that migrate. They fly down the East Coast on their journey south to the forests of Mexico for the winter. (Graphic by Monarch Watch/Carolina News & Reporter)

Arlene Marturano discusses how monarchs are tagged and observed on their migration as part of a lecture series on the butterflies. (Photo by Mollie Naugle/Carolina News & Reporter)