Volunteers at the Free Medical Clinic update patient information before afternoon patients arrive. (Photos by Sydney Zulywitz/Carolina News & Reporter)

About 1-in-10 South Carolinians live without health insurance. That makes the state the 9th-worst in the nation, according to the U.S Department of Health and Human Services.

That’s expected to become even more of an issue as the federal government shrinks the COVID-era expansion of Medicaid.

Six million more Americans are expected to be uninsured within the next five years, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

How will the medical system handle the increase?

Free clinics, where many South Carolinians get their care, think they know.

They’re coaching future providers to be compassionate with people who likely have let difficult health conditions linger before seeing a medical professional.

Teaching compassion

Volunteers at free clinics include nursing students and professors, pre-med students, retired providers, medical students and current providers with a heart to give back.

Student volunteers say they’re developing a better understanding of the uninsured population, to become better providers.

That starts with humanizing the population, said Laura Witt, a volunteer at the Free Medical Clinic in Columbia.

“No one is choosing to not have health insurance or not make enough money to be able to afford health insurance,” Witt said. “So, understanding that literally anything could happen to put people in these situations is incredibly important.”

There’s often a stereotype that free clinics serve “derelicts, drug addicts, drunks, homeless people,” said Freddie Strange, the clinic’s executive director.

But being at the clinic has shown Witt that uninsured people also can be unemployed students, or people who are recently divorced or between jobs, she said.

Holistic care

More than half of all care given at S.C. free clinics is for hypertension or diabetes, according to the S.C. Free Clinic Association.

Both conditions can be treated with lifestyle changes — but some people struggle to afford those changes.

“You could tell anybody all day, ‘Don’t eat a cheeseburger. Eat an apple instead,’” said Jan Kubas, a provider at the clinic. “But the cheeseburger is 75 cents, and the apple is $1.25.”

Free clinics help student volunteers learn the importance of holistic care, said Josie Gardiner, a volunteer at the Good Samaritan Clinic.

For her, it starts with patient education that’s as simple as explaining to diabetic patients how insulin works.

“Just taking the time to explain something to someone empowers them to be more involved in their care,” Gardiner said. “And that lets them be an advocate for themselves.”

Knowledge helps patients make informed decisions about their health, said Patsy Whitney, the Free Clinic Association’s executive director.

Changes in health can help people be better parents, caretakers, employees and citizens, she said.

“If you don’t have your health, it’s hard for anything else in your life to come together,” Whitney said.

And holistic care often means providers become social workers, said Maggie Selph, a care provider at the Free Medical Clinic. It shows student volunteers that clinics are only a “piece of the puzzle,” and that treatment goes beyond a pill bottle, she said.

Student volunteers say they have seen providers help patients apply for food stamps, navigate to the cheapest pharmacies and fill out financial aid paperwork for additional testing.

It’s about teaching students what care can look like when it’s not bound by money and time, providers said.

Laura Herbert is a care provider at the Free Medical Clinic with 30 years of experience as a nurse practitioner. She said there’s a noticeable difference in the care she can give patients at the clinic compared to her work with large healthcare organizations.

At a large organization, she could only address a portion of patients’ issues before the appointment time was up. The patient would have to schedule another appointment if they wanted to get through their list of problems.

“I don’t have that issue here,” Herbert said. “I can take as much time as I want. We can go through the whole list.”

That kind of in-depth care could be an important step toward healthcare inequities, especially when S.C. free clinics serve mostly African-American, Hispanic and Latino patients, according to the Free Clinic Association.

“It’s kind of more equitable in a sense that maybe people who don’t regularly see a doctor need more time to spend with the physician or the (physician’s assistant),” Gardiner said. “And they’re able to get that.”

Future-focused care

A focus on covering a patient’s entire list of problems in one visit may be the reason free clinics survive as their patient population increases.

Kahleek Chapman, the director of development at the Free Medical Clinic, said patients of some medical practices are too often given medications that attack symptoms.

He said the mostly privately funded clinic is focused on resolving the root causes of patients’ conditions.

Funding becomes an issue when donations fall short of what’s needed to do extensive testing and treatment.

So the clinic’s funding must keep up with the increase in the uninsured patient population.

Less than 2% of clinic funding comes from the government. The rest comes from churches, individuals and grants from local organizations and foundations.

This year’s budget is more than $800,000, Chapman said. The amount needed varies annually but will no doubt increase in the next few years.

He’s focused on applying for more grants and diversifying funding streams to meet the goal this year and maintain future funding streams.

But free clinics need more than money to keep up with the increase in uninsured patients, Kubas said. They need providers with the heart to care for people.

That’s why she shows up to the clinic every Thursday to be a compassionate provider and raise student volunteers who will one day step up to do the same.

“High quality healthcare is a basic human right,” Kubas said. “And I think we come into this building with that thought in mind, that everyone deserves the best that we can give them.”

Student volunteers Nabeeha Baig, Somaria Ellis, Abbey Kuebler and Laura Kock

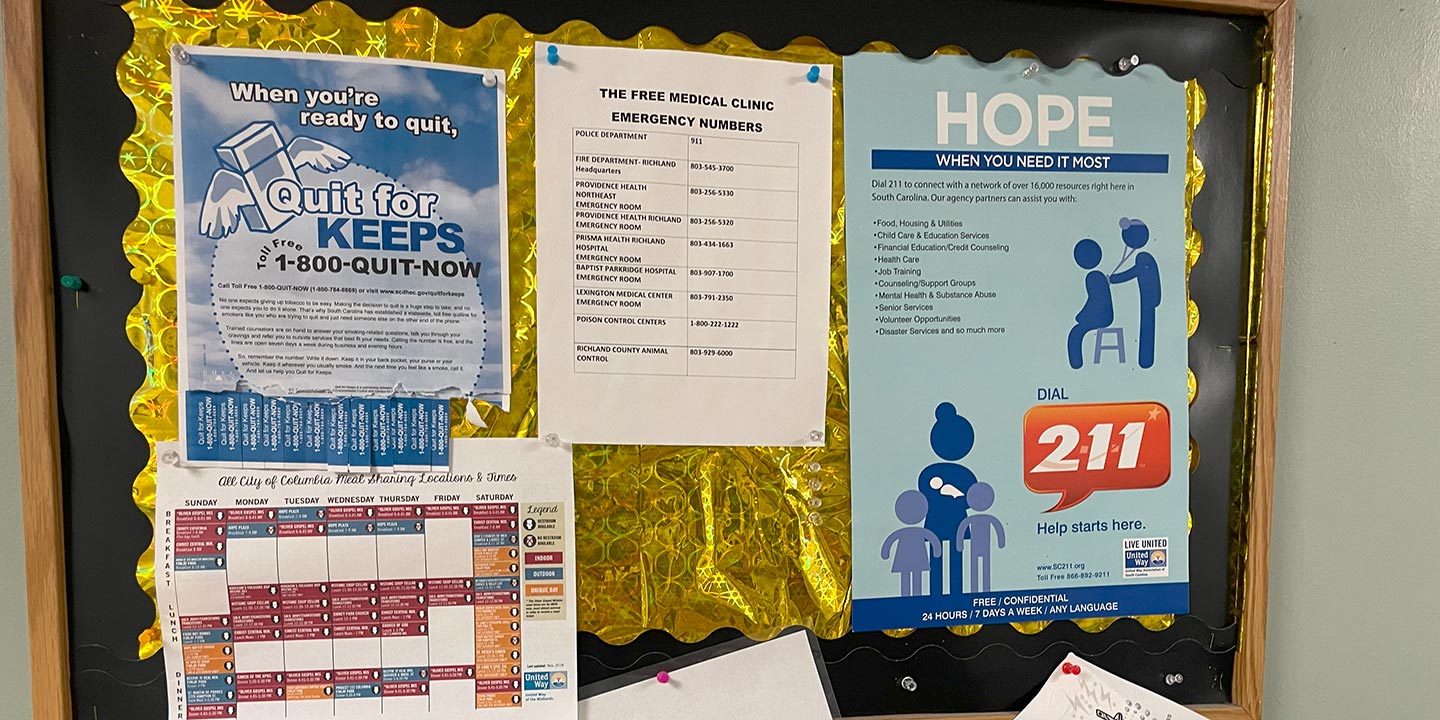

Connecting patients with resources such as food, housing and job opportunities is a big part of clinics’ holistic care.

Nabeeha Baig, a public health student at the University of South Carolina, prepares to leave the clinic after her morning shift.

An exam room at the Free Medical Clinic in Columbia