A dog peers around the corner of its kennel at the Columbia Animal Shelter. (Photo by Macaila Bogle/Carolina News & Reporter)

Cocoa is a 1-year-old gray and white dog who has been living at Columbia animal shelter since mid-June.

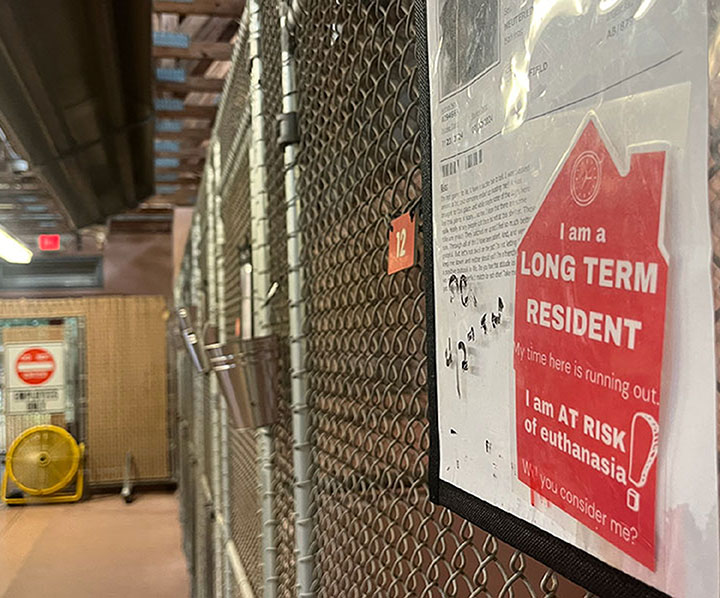

A red tag hangs on her kennel reading, “My time here is running out.”

The sign says Cocoa’s owner suffered financial hardships, was no longer able to take care of her and turned her over to Columbia Animal Services. Volunteers who designed the sign described her as playful but submissive, with “plenty of years of love to give.” But she is still at risk.

Cocoa is the longest-residing pup in the shelter’s Adoption Dog Hall 1. That makes her next in line for euthanasia.

“Losing dogs that are adoptable,” said Mike Young, a volunteer. “You never get used to it.”

The shelter is overcrowded, housing over 150 dogs. It’s an ongoing problem.

In times like these, Adoption Dog Hall 1 becomes a dangerous place to stay. Superintendent Victoria Riles said Adoption Dog Hall 1 houses most of the shelter’s long-term residents who are on the “length of stay” list.

“That is a list that we try very hard to avoid looking at,” Riles said. “But in the event that we have run completely out of space, we have to make decisions.”

If no dogs are up for euthanasia due to medical or behavioral problems, Riles said the list is where CAS turns to make euthanasia decisions. Generally, the dogs on the list have been there 30 to 60 days.

“Because they’ve already had a fair amount of time to be promoted and exposed and they’re still here, we’re going to make euthanasia decisions so that we can allow new incoming residents their time to be promoted and exposed,” Riles said.

Riles said in cases like Cocoa’s, times of financial hardship increase the shelter’s intake of abandoned and surrendered animals. The shelter saw a peak intake in 2008, during the Great Recession, then then again at the end of COVID quarantine. Rates are going back down now.

Columbia’s shelter is working toward the No Kill South Carolina 2024 initiative adopted by counties across South Carolina. The program focuses on implementing “life-saving and humane strategies,” with the free adoption program serving as a key approach.

Intake rates have dropped in the past year by half, and euthanasia rates fell 5%.

Programs have helped, Riles said.

Free adoptions as well as trap, neuter and release programs are successful. And people with pets they’re wishing to re-home can search for homes for the animals on the shelter’s website.

Still, 778 dogs were euthanized this year, with 4,873 entering the shelter. Some 66% of these dogs came from Richland County, outside of the city of Columbia.

Columbia Animal Services is the city’s municipal animal shelter. Richland Country oversees its own animal care and control but doesn’t have an animal facility of its own.

Richland County pays $25.52 per dog per day for the city shelter to house its strays.

If a county dog comes in with identification, the county pays for a 14-day hold. But if the dog has no identification, the county only pays for five days.

That doesn’t mean the dogs are euthanized after that. It just means less money for the shelter.

City taxpayers are responsible for the remainder of the shelter’s budget.

Young has been volunteering at the shelter for two years. He also runs a company that cleans out homes and realized that many of the items he removed would be great to donate to the shelter. Then he decided to become more involved as a dog walker and adoption ambassador.

Young said there has to be a better option.

“The city would likely be ‘no kill’ if we didn’t have the county dogs coming in,” Young said.

To save lives, something needs to change, he said.

“None of us want to see any dogs be euthanized, whether it’s here at any other shelters,” Young said. “There has to be a way that we could work together to either educate the public, have fewer strays, have spay and neuter laws, or have better options for dogs that are surrendered.”

One way to handle surrenders is to promote the dogs before the owners give them up, so they never end up at the shelter.

Cocoa’s story doesn’t have to end in euthanasia. She could be fostered, selected by a rescue shelter that will continue to try to find her a home or permanently adopted.

Abigail Lieber, a junior psychology major at the University of South Carolina, adopted a dog named Floyd on Aug. 23. Floyd had been staying in a foster home when Lieber discovered him through the shelter’s Facebook page.

“They were super helpful,” Lieber said. “They gave me all the information I needed, all the medical records, and got me started with his meds and everything.”

The shelter values any level of involvement from the college student population, Riles said.

“We’re really all about being a public service educating our community in hopes to create a no-kill community one day,” she said.

Cocoa, a long-time shelter resident, in a playpen at the Columbia Animal Shelter (Photo by Macaila Bogle/Carolina News & Reporter)

Kennels line one side of the wall, and supplies line the other in Adoption Dog Hall 2. (Photo by Macaila Bogle/Carolina News & Reporter)

A red sign hangs on a dog’s kennel at Columbia Animal Shelter, indicting the dog has limited days left in the shelter. (Photo by Macaila Bogle/Carolina News & Reporter)

Source: Columbia Animal Services/By Macaila Bogle, Carolina News & Reporter

ABOUT THE JOURNALISTS

Mary Gaughan

Gaughan is a journalism major at USC with a concentration in sports media and a minor in sports and entertainment management. She interned at Charlotte Motor Speedway last summer, rotating through five departments. She plans to pursue a career in sports communications and public relations after graduating this December.

Macaila Bogle

Bogle is a third year multimedia journalism student at USC. She has been a member of the student-run Daily Gamecock for five semesters and now serves as the managing editor for news and the arts and culture section. She hopes to work as an editor or arts and culture reporter after graduating in December and eventually to teach at the college level.