Lorri and Dan Unumb with their sons Ryan, Christopher and Jonathon (Photo courtesy of Lorri Unumb/Carolina News & Reporter)

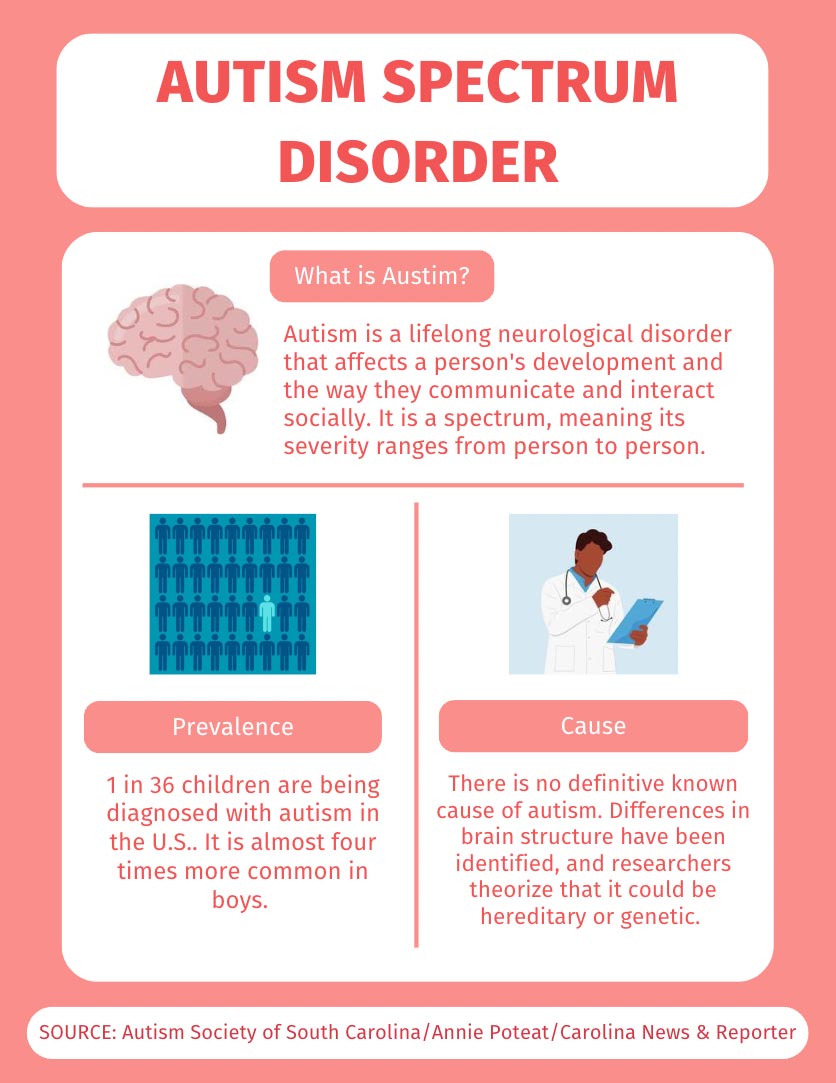

South Carolinian Lorri Unumb was living in Washington, D.C., where she and her husband Dan were lawyers when their son was diagnosed with autism just before his second birthday.

Medical experts told them plainly: Ryan’s “only shot” at a functioning life would be with specialized therapy to develop his behavioral and communication skills. It would be intensive. It would require 40 hours per week. It would cost about $70,000 annually for years.

And none of it would be covered by insurance.

The couple moved back to South Carolina to be closer to relatives and came up with a plan: The family would live off Dan Unumb’s salary. Lorri Unumb’s salary in her new job as a Charleston School of Law professor would cover Ryan’s therapy. They made it work, but they knew things needed to change for other families.

“It was painful to think about other children and other families who couldn’t do that,” Lorri Unumb said. “That is so wrong, that in the United States of America, if you get autism, you only are going to get treatment if you have been born into a wealthy enough family.”

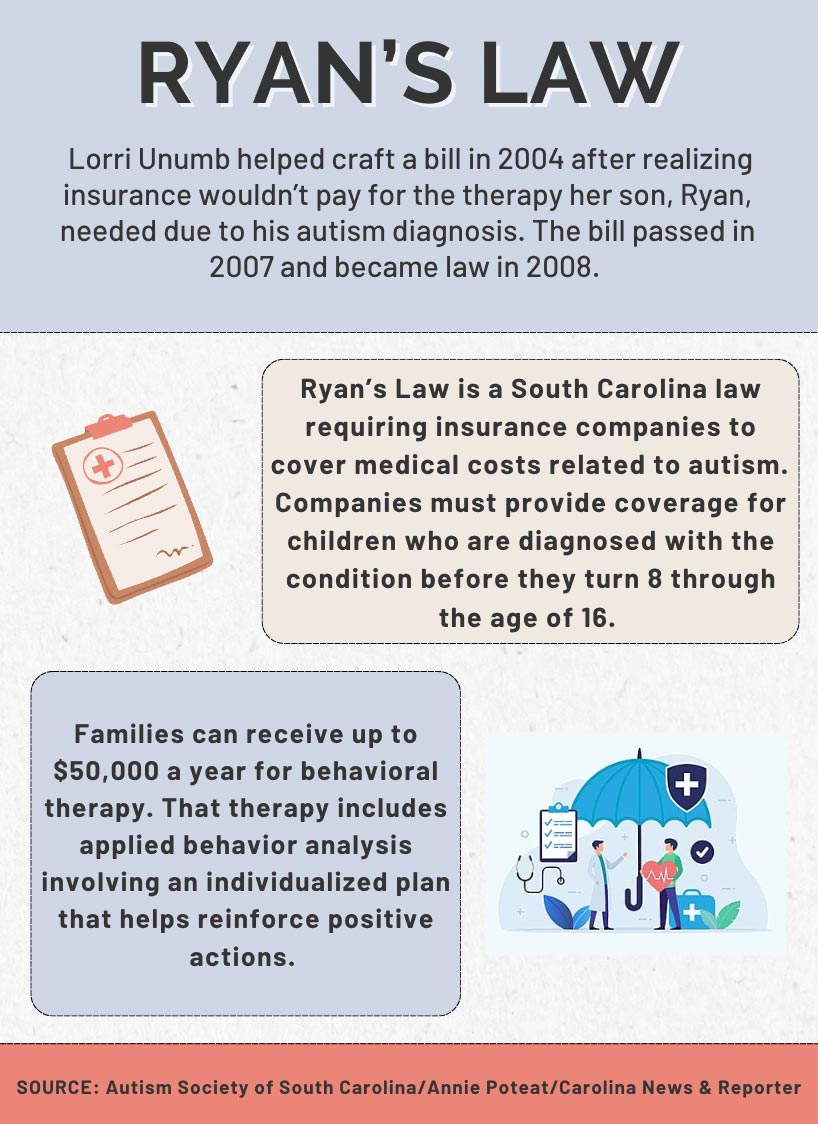

Lorri Unumb began to draft a bill for state lawmakers to consider. It would require health insurance to pay for evidence-based and doctor-recommended therapy for autism.

“Here are families who are paying their premiums for health insurance every month.” she said. “… But they’re not getting the benefit of the bargain, because the diagnosis is autism.”

In 2005, state Rep. Nathan Ballentine, R-Richland, filed the bill aimed at helping. It went through amendments for almost two years before passing, requiring insurance companies to pay up to $50,000 yearly toward specialized therapy and autism-related medical care for those under 16 years old. The bill also requires insurance companies to provide health coverage to someone diagnosed with autism before they are 8 years old until they are 16.

Then-Gov. Mark Sanford vetoed the bill on June 6, 2007. The Unumbs and their peers convinced the House and the Senate to override the veto the following day. The bill passed unanimously and went into effect in 2008.

Word of Ryan’s Law got around. Lorri Unumb started to hear from families living in Kansas, Oregon and all over the country asking for her help to pass the law in their states.

Reaching out nationally

That’s when Autism Speaks, a national nonprofit dedicated to fundraising and advocacy for autism, contacted Lorri Unumb to offer her a job replicating Ryan’s Law across the country.

“I spent the next decade traveling the states and helping in every state,” Lorri Unumb said. “I would meet with families. I’d meet with providers, find some legislators who were sympathetic to our cause and open-minded. And I would help them draft the legislation.”

There is now a variation of Ryan’s Law in all 50 states thanks to Lorri Unumb – a concerned mom who decided to make a change.

She wasn’t done there. Lorri Unumb and her husband were helping their son receive his therapy with specialists who came to their home. But they wanted him to have a treatment-based center to attend.

The family considered moving to another state that has treatment centers for Ryan Unumb, but they wanted to stay in the same state as their relatives.

“We could pick up and move to New Jersey,” Lorri Unumb said. “But if we do that, then we have solved the problem for exactly one child – Ryan.”

They founded the Unumb Center for Neurodevelopment in Columbia in 2010 to provide autism medical services to people across South Carolina.

Lorri Unumb is now focused on a new goal: addressing the lack of resources for adults who have autism.

Lorri and Dan Unumb are building an adult residential campus in Lexington called Unumb Place. It will have six group homes on the campus and is set to open in 2025.

“I am very excited about building this permanent place for our son to live and other people like him,” Lorri Unumb said. “So many families are faced with that just awful time of having to place their child residentially, which I applaud families who do that because mom and dad are not going to live forever. … It’s not fun.”

A residential home allows someone with autism to live independently. It offers the opportunity to socialize with peers in a safe environment with around-the-clock specialized medical staff.

Advocating for special education

Kim McHugh is working to help South Carolinians, too.

McHugh’s son has autism, and like Lorri Unumb, she has dedicated her life to helping other parents who are in her shoes.

“There were no parent support groups,” McHugh said. “There was nothing. It really left me feeling isolated, like I was the only one in the world who had a kid like this. It was tough.”

McHugh works for the Autism Society of South Carolina as a parent mentor in the Parent-School Partnership program. She helps teach parents about their children’s legal and civil rights in the education system.

“We’re all parents,” she said. “We’re all moms with kids with autism. But special education is guided by legal policies and procedures. I’m old enough that when I was in high school, you didn’t see people with neurological differences. Those that were more severe just weren’t allowed to go to school. … Isn’t that terrible?”

McHugh meets with families daily to obtain and process their children’s Individualized Education Program and the services they are eligible for in public schools. An Individualized Education Program is a written plan tailored to someone in need of special education.

“I had to advocate for my son to get a communication device, to get social skills training for him, to be in general-ed most of the day – with a whole lot of support,” McHugh said. “I was advocating fiercely for him, and I thought, well, ‘I could do this with other people, too.’”

Taking pressure off mothers

Laura Friedman brought her familial experience with autism to her workplace as well.

She is a speech pathologist and a postdoctoral fellow in the SC Family Experiences Study at the University of South Carolina.

“I personally have an older sister with autism who still lives with my parents and needs a lot of support when it comes to things like showering, eating meals – just sort of basic daily living tasks,” Friedman said. “She’s the reason why I went into speech pathology in the first place. She’s the motivation behind the work that I do.”

Friedman is researching the aging trajectory of mothers who have autistic children. She is interested in a person with autism’s transition period between high school and young adulthood, and the impact that time has on their mother.

“Mothers of children with disabilities, relative to the general population, are at higher risk for things like depression, loneliness or (poor) sleep quality,” she said. “And we know that all of those are risk factors for atypical or accelerated aging.”

When an autistic person reaches adulthood, there is a drastic drop in services, and that’s a stressful time for mothers, Friedman said.

“They go from having therapy set up and having their kids be supported in school-based systems to just being left on their own,” she said.

But the scariest part of a mother’s life with an autistic child is what will happen when the parents can no longer care for them, Friedman said. They wonder where their child will live, how they’ll handle it and who will care for them.

That’s what drove Lorri Unumb to build Unumb Place and continue advocating as her son grows up. Ryan is now 23 years old.

She constantly receives letters, emails and phone calls from parents across the country expressing their thanks.

A mom to a 4-year-old with autism sent Lorri Unumb a picture of her child on a tricycle. But without specialized therapy, he wouldn’t have been able to ride that tricycle. And without Lorri Unumb, that family wouldn’t have been able to afford therapy.

“It’s really hard for me to talk about, but people all over the country write me with stories like that,” Lorri Unumb said. “That’s all I need right there.”