A bridge over the Wateree River in Sumter County is being renovated. (Photo by Holly Poag.)

For the first 20 years that Pete Poore worked at the South Carolina Department of Transportation, his job was to find emergency solutions for the state’s worst roads and bridges.

“There was some paving and emergency paving and that sort of thing, but generally, we couldn’t follow our formula of resurfacing roads every 10 to 14 years,” Poore said. “So basically, we had a backlog of work to resurface.”

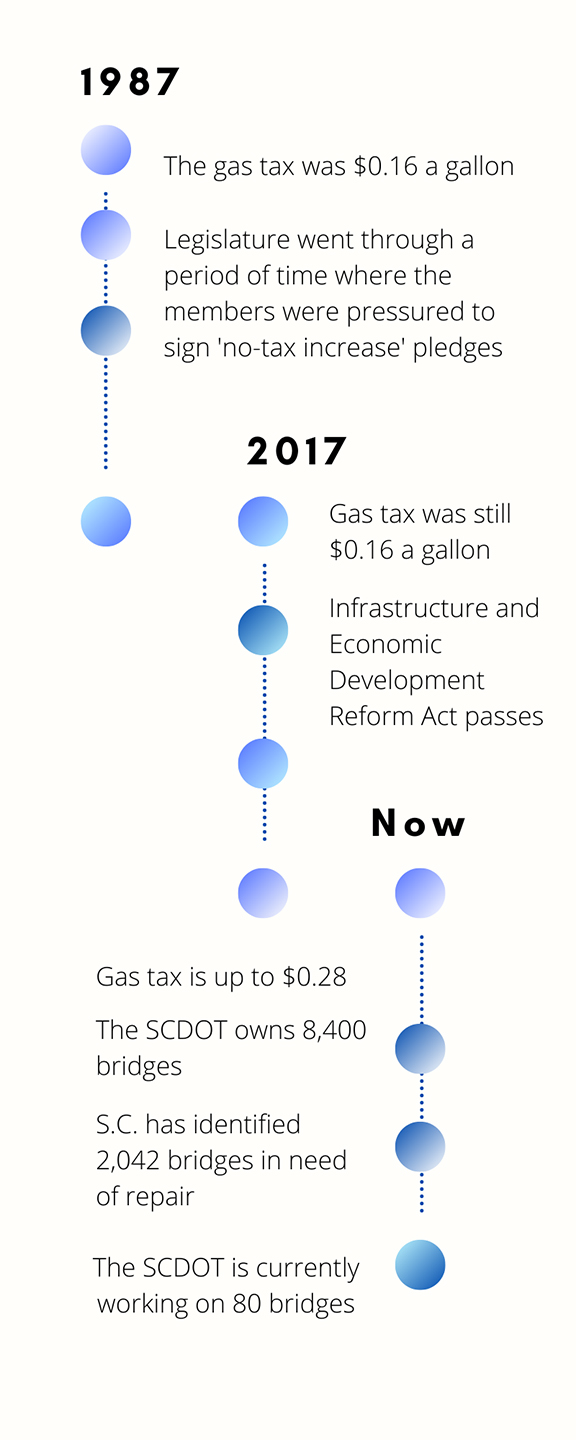

It’s a backlog 30 years in the making. In 2017, state lawmakers increased funding for the department of transportation — the first such increase since 1987.

“We can’t do it all,” Poore said. “We can’t make up 30 years of deferred maintenance in 10 years.”

Nevertheless, the department is now halfway through its 10-year plan playing catch-up on the state’s roads and bridges.

Key among the work is roads that run over bridges, because those surfaces wear down quickly. More than half of South Carolina’s bridges have a rating of “fair,” meaning they are one step away from requiring major rehabilitation, one S.C. expert said.

In total, South Carolina has identified 2,042 bridges in need of some repair, which will cost around $2 billion. The transportation department is repairing 80 state bridges.

The Carolina News & Reporter looks at where the department’s progress stands.

THE PROBLEM — HOW WE GOT HERE

In 1987, the gas tax in South Carolina was 16-cents per gallon. In 2017, it was still 16-cents per gallon, making it the lowest gas tax in the Southeast and fourth lowest in the nation.

“A lot of the Legislature went through a period of time where the members were pressured to sign ‘no-tax increase’ pledges,” Poore said.

In addition to the low taxes, the state has a large number of roads and bridges and both are in unusually bad shape.

The state DOT can’t afford so many roads. The department’s 2019-2020 budget — it’s most recently available — was $839 million, according to its website. By comparison, North Carolina’s transportation budget for the 2021-2022 is $5 billion, according to its website. Most of the budget comes from that state’s gas tax. Georgia has a transportation budget of $2 billion.

“South Carolina has one of the largest, one of the most extensive roadways network in the country,” said Fabio Matta, a USC engineering professor. “So the state funding has to take care of maintenance and rehabilitation of a major infrastructure network.”

How does a state as small as South Carolina have one of the nation’s largest road networks?

In the 1920s, the federal government jumpstarted employment through a highway-building program, according to the the S.C. DOT. There was a catch, though: Only state roads would receive aid. Local governments pushed for the state to own the roads so they could receive federal money.

Today, South Carolina’s highway system is the fourth-largest state-maintained system in the country, with 41,500 miles of roads.

Lawmakers want to give the roads to the counties for maintenance. But counties are fearful the state won’t provide funding to keep them maintained.

To compare, Georgia has the country’s most state-owned roadways, 90,000 miles, while North Carolina has the second largest, with 78,000 miles.

However, North Carolina ranks as having the fifth-best roadways in the country, and Georgia ranks 14th, according to a 2021 Annual Highway Report by Reason Foundation.

Those states’ roads, of course, have more funding.

SO HOW BAD IS THE PROBLEM?

The condition of South Carolina’s roads rank them last in the nation.

The 2017 S.C. Infrastructure and Economic Development Reform Act is working on that ranking, largely by increasing the gas tax. The 16-cents-per-gallon tax enacted that year by lawmakers is already up to 28-cents-per-gallon. By 2028, it will be 50-cents-per-gallon. For comparison, North Carolina’s gas tax is 38.5-cents-per-gallon. But both states a have larger populations than South Carolina, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, so they can bring in more money.

A focus of the 2017 infrastructure legislation is on roads over bridges.

In 2018, the number of bridges in South Carolina that were rated as “fair” surpassed the number of bridges that were rated as “good,” Matta said.

The 2017 legislation allowed a 12-cent increase over the past six years.

With an increase in funds, the department laid out four programs in a 10-year plan, with one of the programs focusing solely on bridge replacements.

Of the 9,395 bridges in South Carolina now, 8,400 are state-owned, Poore said.

Of the total, 499 are classified as structurally deficient, according to a report by the American Road & Transportation Builders Association. But that’s an improvement from the 781 bridges classified as structurally deficient in 2017.

The S.C. DOT inspects bridges every two years on average, Poore said. If the department determines that a bridge needs to be watched carefully, it labels it as in “poor” condition and inspects it every year.

Engineers say there are two major concerns for a bridge’s structural integrity: the roadway over the bridge, and the chances that items, such as something called “scour” slamming into bridge pillars.

Scour is debris in the water, such as trees, that can slam into bridges and can cause cracks and other damage, Poore said.

“We do have routine inspections,” Poore said. “It’s hard to see down there but we do the best we can. And when we determine that a bridge has ‘X’ amount of scour, then it’s time to go out and clear that scour out.”

The structure of a bridge itself is rarely an issue.

“The failure is in the roadway itself,” Poore said. “The structure is fine, there’s nothing wrong with the structure. But the roadways on bridges are so torn up.”

For Matta, coastline bridges are a top priority because they often serve as hurricane evacuation routes.

“If one of these bridges goes (out of use), or becomes unusable, then what are the emergency vehicles going to do?” Matta said. “How can we serve people who live in those areas? And by all accounts, we’re talking about a lot of citizens.”

Florida lived that reality in the aftermath of Hurricane Ian. Sanibel Causeway, a 3-mile, three-part bridge connected by islands, has proven difficult to repair. Temporary repairs re-opened the bridge three weeks after the hurricane.

With half of South Carolina’s bridges being in “fair” shape — close to needing immediate repair — “maintenance is so important. These bridges are here to stay,” Matta said.

The DOT said bridges typically have a lifetime of 50 years to 60 years.

South Carolina has about 2,800 small bridges in the state — many of which still have wooden pylons, Poore said.

“We don’t want to put band-aids on bridges,” Poore said. “But if we can extend the life and maintain the safety of a bridge, we will certainly do that. But our main goal is to replace bridges that haven’t been (repaired), that have extended or have exceeded their time frame, their lifespan.”

Old Tamah Road bridge in Irmo recently underwent construction. (Photo from SCDOT)

The finished product on Old Tamah Road bridge in Irmo (Photo from SCDOT)

A bridge on U.S. 321 was under construction near Camden. (Photo provided by SCDOT)

Completed construction of a bridge on U.S. 321 near Camden (Photo provided by SCDOT)

Workers repair a bridge on U.S. 378 over the Wateree River. (Photo by Holly Poag)

A timeline of the transportation funding (Graphic by Holly Poag)