Retired arborist Tom Knowles has been mapping trees for more than 20 years. He once relied on a huge paper map but now uses updated software. (Photos by G.E. Hinson)

Afternoon shadows silhouette monstrous oak limbs on lush green grass. Picnic blankets and hammocks dot the shade of a decades-old tree canopy.

The wind blowing through leaves disguises blares of car horns, booming speakers and roaring engines.

The University of South Carolina’s urban fairytale forest is tucked into the center of Columbia’s sprawling concrete jungle. Tom Knowles has spent nearly a year mapping the thousands of trees because although they seem magical, they can’t thrive alone.

Knowles began mapping trees last May, a month after retiring as an arborist. He was USC’s director of grounds for 21 years but never had time to start the project.

He has dedicated a lifetime to caring for trees. And he isn’t done yet.

“It’s the most important thing in the world,” Knowles said.

More than 7,800 trees already have been mapped by Knowles.

Just Knowles.

And his iPad.

One of the biggest benefits of mapping, Knowles said, is that it allows the grounds team to ask and answer the question: “How are we going to manage our trees on campus?”

The process

Sometimes it looks like Knowles is deciding whether a tree deserves a parking ticket.

He gazes up at its branches and clutches an iPad.

But he’s mapping trees on USC property.

By himself.

A geographic information system is a computer system that allows users to collect and store data based on location. Knowles uses the software to collect tree data that will help USC’s grounds team.

“We look at trees as another infrastructure element, another asset of the campus,” Knowles said.

Information collected by Knowles is essential to taking care of that asset.

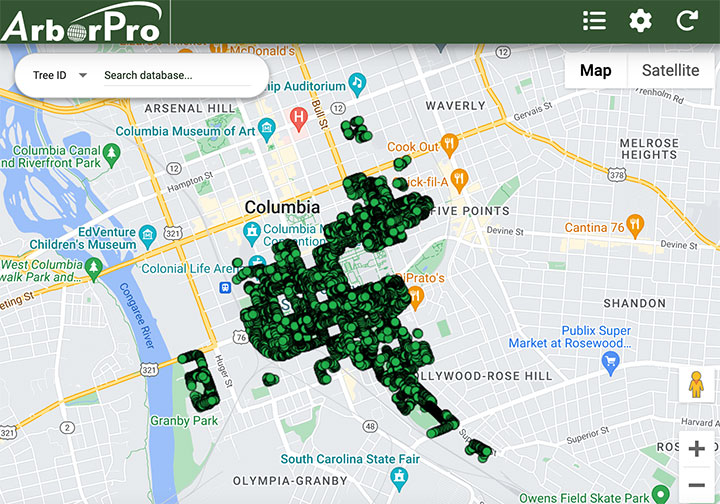

The software opens to a birds-eye view of a sprawling map littered with green dots, each representing a tree Knowles has already visited. Those green dots house the data he collects.

A little cartoon man marks Knowles’ GPS location on the satellite map. Knowles uses the program’s aerial perspective to look through the tree’s canopy and mark the trunk’s position on his map.

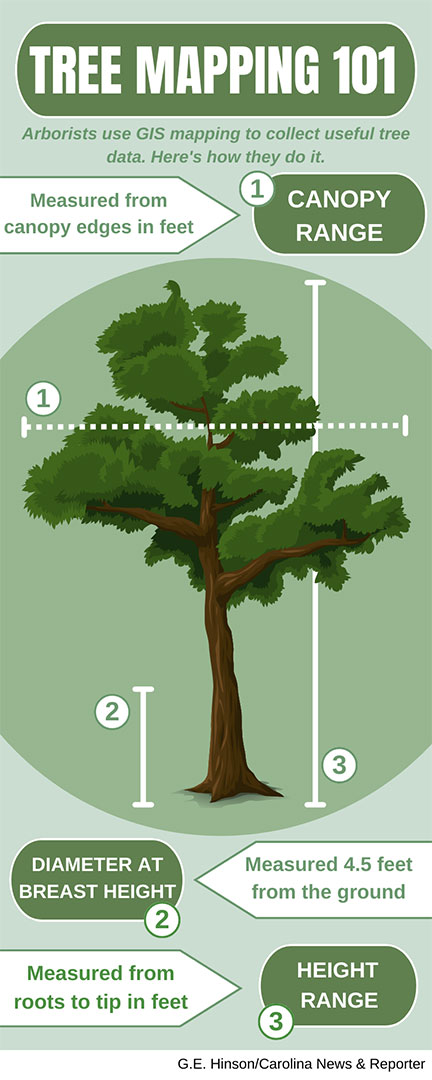

Knowles documents general information such as the species, location and condition. He also collects more complex information – the tree’s estimated diameter and height, its canopy range and the number of trunks.

Some of the most important information he collects is what the tree needs, Knowles said. Pruning, removal or just a closer eye.

“Is it safe? That would be priority one,” Knowles said.

Knowles plans to be finished mapping by the end of March. He expects to map more than 9,000 trees on USC’s sprawling property across central Columbia.

Knowles logs more than 11,000 steps on his phone each day he works. He surveys and photographs 100-200 trees per day.

With no tree left behind.

By himself.

The purpose

Thousands of trees mean tens of thousands of data entries on the GIS software.

“It’s going to be a big step forward,” said Emily Jones, a landscape architect at USC. “It’ll give us sort of a quantitative view of how we’re doing as an urban environment, how we’re doing in terms of the health of that canopy.”

The data that Knowles is gathering will be used in part to take better care of USC’s trees.

What if a disease was ravaging laurel oaks in the Southeast? Crews can pinpoint and monitor all of USC’s laurel oaks.

What if a monstrous storm passes through? Crews can locate trees that are in less than perfect condition to make sure they’re still healthy.

Knowles’ map will help generate faster solutions to big or small problems. It also could help enhance the development of USC’s urban forest in a different way.

Columbia is famously hot. USC’s urban forest helps shade students and visitors during the extra-long summer months.

“If we have more data like that, we can hopefully make the case to the powers that be that the urban forest is really critical,” Jones said. “We should be planting more trees and making up for the loss of trees.”

Only about 11% of USC’s campus is considered well-shaded, Jones said.

The impact

Garey Weaver is a senior mechanical engineering major at USC.

She spends nearly all day bathing in fluorescent lights. Her classrooms are enveloped in blindingly artificial light.

None of those rooms have windows. Neither does her office.

In the winter, Weaver starts her day in the dark, spends all day trapped inside fluorescent caves, and then ends her day in the dark.

“Access to green spaces gives me a break from all of that,” Weaver said. “I feel like I can just step outside and breathe. It helps me reconnect with myself and remember why I’m doing what I’m doing.”

The little patch of green in front of USC’s Swearingen Engineering Center brings her back to reality. For some, green spaces are key players for a balanced life in a sprawling urban landscape.

Others suffer from plant blindness.

“You could be sitting at a bench with beautiful blooming shrubs around and some students would not pay attention to it because they’re so disconnected to it because of technology,” said Dr. Todd Beasley, an education professor at USC with years of professional horticulture experience.

He believes that access and exposure to green spaces are essential. So he designed a project for some of his education students with the outdoors in mind.

Beasley’s semester-long journaling project encourages his students to visit green spaces in Columbia and write about them.

To put down their screens and take in the wonders of giant trees and colorful blooms in the middle of Columbia’s concrete maze.

“It’s part of the health and well-being of people, just taking a walk through this campus to see these trees,” Beasley said. “It gives us that nature prescription.”

A GIS map of USC’s trees will be available to the public near the end of March.

Knowles marks and collects data on his iPad. After he wraps up for the day, he makes changes on a desktop.

The Horseshoe on USC’s campus has several oak species. Willow oaks, laurel oaks, red oaks and white oaks provide ample shade.

A pecan tree on USC’s campus spent more than a decade growing through a chain-link fence.