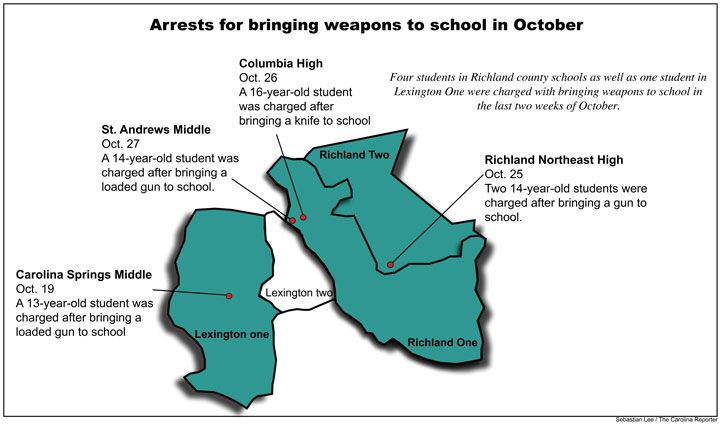

In the last two weeks of October, five students were involved in incidents bringing weapons to schools in the Midlands area. Photo by Hannah Wade.

This story was updated on Nov. 4, 2021.

In the last two weeks of October, four Richland County students were charged with bringing weapons to school. A fifth student, in Lexington County, was also charged with a weapons violation.

For those charged with keeping schools safe, the reports are troubling, but not unexpected. They suggest an increase in violence across the state as well as an ongoing mental health crisis in school-aged children are contributing factors for these incidents.

“Schools are a microcosm of their communities, and it’s inevitable that the level of violence in our communities right now would be brought into schools, and we’ve seen that,” said Mo Canady, the executive director for the Alabama-based National Association of School Resource Officers.

The number of firearm-related incidents in or near school campuses has increased across the nation. There have been nearly 113 incidents since Aug. 1, with 12 of them being in South Carolina schools, according to Canady.

Violence in schools a symptom of rising violence in communities

In a June 2021 press release, SLED, the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division, announced preliminary crime statistics for 2020. South Carolina’s rate of murders went up about 25% while aggravated assaults were up 9%, according to the release. Canady said school resource officers were preparing for an uptick in these incidents in schools.

The incidents occurred at four different Midlands schools – Richland Northeast High School in Richland 2, Columbia High School and St. Andrews Middle School in Richland 1, and Carolina Springs Middle School in Lexington 1.

Richland 1 schools have put up signage that discourages bringing weapons to school and generally encourages students to let someone know if they see something, according to Superintendent Craig Witherspoon.

He urged parents to take preventative steps as well like communicating with their children, checking their bookbags and being involved in their school.

Students’ mental health declined during COVID-19 pandemic

Mark Weist, a psychology professor at the University of South Carolina, partially attributed the string of incidents to pandemic fatigue.

“I think we know that it’s pretty much an unprecedented mental health crisis for everyone, including children in schools,” Weist said.

For middle and high school students, aged 12 to 17, emergency department visits related to mental health increased 31% between January and October 2020, according to a report published by the U.S. Department of Education.

The report also found that the pandemic created more barriers for students to get access to mental health resources.

“Even before the pandemic, mental health challenges facing children were a great concern, but COVID-19 has exacerbated underlying mental health conditions,” said Dr. Margaret Meriwether, the director of school mental health services for the S.C. Department of Mental Health.

Superintendent Witherspoon said the school district utilizes resources like trauma-informed training for teachers and staff, mentorship programs for students and mental health programming.

For the district’s approximately 22,000 students, there are around 30 social workers, which is about one social worker for every 733 students, according to Witherspoon.

Is there a solution?

Canady, a former resource officer himself, said he “would love to see a situation where for every SRO in this country, there is a school psychologist paired with them.”

The National Association of School Psychologists recommends that states have at least one school psychologist per 500 students. South Carolina has one school psychologist for every 1,413 students, according to data, which is only a couple hundred away from the national average of one per 1,211 students.

“School safety, in regards to weapons, is a multi-layered issue and requires a multi-disciplinary approach, a multi-hazards approach, and SROs are a layer of that,” Canady said.

Each school in Richland 1 has at least one school resource officer, according to Witherspoon, with some of the larger high schools having multiple. Resource officers focus on building trust with students to help curb incidents like these.

“Our SRO program is such that students feel comfortable talking with them and administrators and so forth and try to have that climate and culture that we do find out and we can take appropriate steps so that no one gets hurt,” Witherspoon said.