Gabby Baressi is graduating from USC’s College of Engineering and Computing in May. With determination and resilience, she has been able to stick with her civil engineering major. (Photo by Caroline Barry)

Engineering and computing are male-dominated fields, but that doesn’t mean women aren’t stepping up to the plate and claiming their place in classrooms and the workplace.

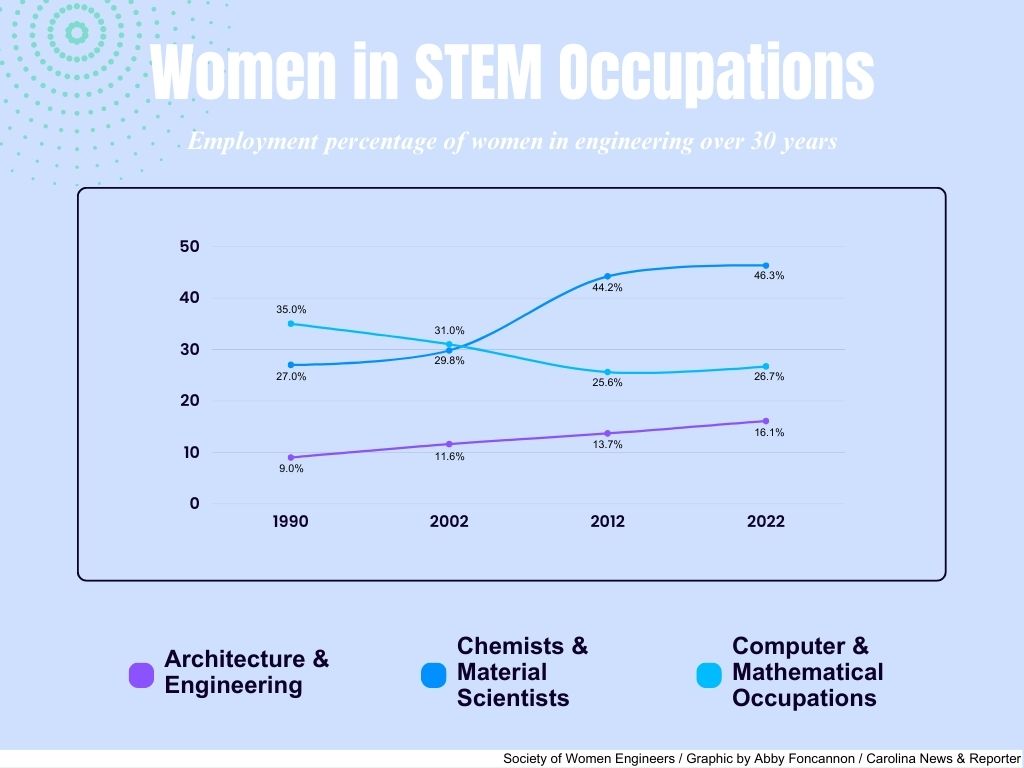

The United States has seen a slow and steady increase in the number of women entering STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) occupations.

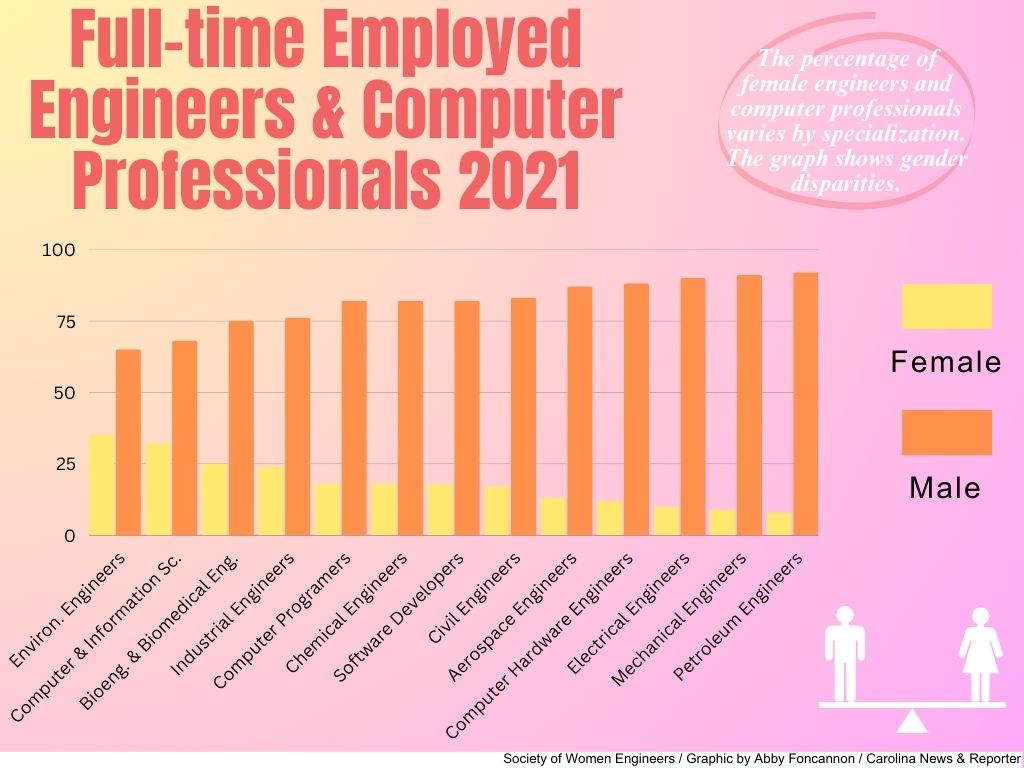

While life science occupations, such as biology, have closed the gap between the percentage of men and women working in these fields, the percentage of women in engineering has slowly increased in the last three decades, according to the Society of Women Engineers.

Young women, whether they are in middle school or high school, are doing their part to follow their dreams and shrink the gap between men and women in the STEM world.

The same is true for female students and professors at the University of South Carolina.

“Go for your dreams,” said Jennifer Naglic, a fourth-year chemical engineering doctoral student at USC’s College of Engineering and Computing. “Just because you’re a woman or a mother or whatever doesn’t mean you can’t do this. … It’s been tough, but it’s definitely doable.”

Young women in STEM

Gabby Baressi is a fourth-year civil engineering major, also in the College of Engineering and Computing.

Her major has included classes in environmental, geotechnical, transportation and structural engineering.

“I think in terms of gender breakdown, civil may have one of the higher rates of girls,” Baressi said. “Just because of how broad of a major it is.”

Looking further into the specific disciplines, such as structural engineering, the field is mostly male dominated.

“For me, it was more so wanting to prove myself in a college at USC that’s mostly male dominated,” Baressi said.

She said she was surprised by how few women there were in her classes. She also noticed a divide between the young men and women in her first-year classes.

“It would be a lot of, like, the girls working with the girls, and the boys working with the boys,” Baressi said.

But she saw a shift in classroom mentality in her second-, third- and fourth-year classes. She noticed that male students began to work with their female counterparts after seeing that many of them had taken part in reputable internships.

“That has been a product of the girls having to work harder to just prove themselves,” she said. “… I think it took the boys a while to see that.”

Baressi and her female classmates also have had to prove themselves to some professors.

Baressi recalled a day when a female friend raised her hand in class to answer a question. The professor called on her but told her that the answer she gave was incorrect. A male student answered the question with the same answer she had given and was told he was correct.

It stunned Baressi, her friend and other classmates that the professor looked over her friend’s answer, even though it was correct.

“Was she just quiet? Did he not hear? Did he kind of blow her off pretty quickly because she was a girl?” Baressi remembered asking herself. “And she was the first one to speak up.”

She understands that being a woman in engineering means having to face situations such as this.

“You may have to speak a little louder,” she said. “You have to get your point across a little quicker because you may get blown off. … And trying to deal with that, you laugh about it at the end. But I think it may go a little deeper than that.”

Baressi worked as a hydrology intern at the Michael Baker International office in Columbia during the summer before her senior year and her final fall and spring semesters.

She was the only woman in her department.

“You’re kind of walking on eggshells,” Baressi said. “… You feel like you have to overcompensate being a young person in our generation. I felt the same way as a girl. You want to prove yourself quickly.”

Baressi recently accepted a position at Kimley-Horn, a civil engineering consulting firm in Washington, D.C. The firm was ranked one of the best workplaces for women in engineering by FORTUNE in 2022.

Despite the hardships she and her female friends may have faced in the classroom and in internships, Baressi thinks a number of her professors made all the difference.

“I have had some fabulous professors,” she said. “… Those are the ones that make you really want to stick with it and make you want to push and not be better than the boys, but prove yourself to the boys.”

Adam Burke, a USC Honors College chemical engineering alum, is currently in a master’s degree program in chemical engineering.

The chemical engineering department is male-heavy on the faculty side, with only three female professors in the department, Burke said.

“I can imagine that’s got to be kind of tough to see,” he said. “If you’re aspiring to become a professor and you (look) well up (into) academia, at least on the South Carolina side of things, it’s basically only men.”

So he empathizes with women in the engineering field and his fellow female classmates.

“It is more of an uphill battle, I would imagine for female students, especially in engineering,” Burke said.

Time management and resilience are key components in making it in the engineering world, he said.

“It’s the name of the game,” Burke said. “… If you enjoy doing it, at least in part, then push through it. Because it is work, but there is an upside. It gets better.”

Educators in STEM fields

Sharon Gumina is an integrated information technology instructor at the College of Engineering and Computing. She teaches classes in cybersecurity operations and software design.

Gumina notices the ratio of female-to-male students in her classrooms is significantly skewed.

“(Women) are always a minority in my courses,” she said. “I would say for every one they’re always a minority, which is a continuation over the past few decades. The numbers are not rising significantly.”

Gumina is frustrated by the lack of women in her field. She said the problem starts before college.

“I think we have not reached females adequately, and it’s frustrating to me because they are capable of doing the work,” Gumina said. “… I think it’s happening at the middle school level, and I can’t fix that. But I think females are getting discouraged somewhere in our educational system.”

Female students at the middle-school level are getting subtle messaging that is preventing them from wanting to reach their full potential in STEM, she said.

Gumina said she tries hard to create an equal platform for her female and male students. She is used to working with men in the industry and in academia, so she has adapted herself to a male-dominated workplace.

“I worked in network security, and there were 300 people,” she said. “Only six of us were female.”

Gumina believes that women in the engineering and computing fields need to have more confidence in themselves and believe in their capacity.

“We’re all human beings first. Gender is second,” Gumina said. “And every female student of mine is capable of coding as well or better than any male student. And they need to know this about themselves. STEM is not a female or a male thing. It’s a human thing.”

She thinks female students shouldn’t listen to the subtle messaging and the microaggressions that may occur on a daily basis in the classroom or workplace.

“You’re going to have to work hard and be good at what you do to get recognition,” Gumina said.

Gumina has found that even though she works in a male-dominated field, academia is where she has found the best workplace for women.

“I do think there is an effort at the College of Engineering and Computing to encourage diversity and inclusion,” she said.

Biomedical engineering might be different than cybersecurity operations and software design.

James Blanchette teaches biomedical engineering. He sees a fairly different ratio of male-to-female students in his classes than Gumina.

“I would estimate it’s probably between 55 to 60% female,” Blanchette said. “… I think it’s very equal. I haven’t noticed any differences.”

Working primarily in academia also might make a difference, Blanchette said.

Women have always been in his field a fair amount, he said.

“The first lab I worked in after I got my bachelor’s degree was run by a woman,” Blanchette said.

He also participates in recruiting events for biomedical engineering, conveying to female recruits that the ratio between males and females in the field is not as uneven as they may think.

“The classes that you’re going to take in the major are probably going to be at least 50/50,” he said. “And in many cases, there will be more women in those classes than men.”

Naglic received her bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering from USC in 2019 and is completing her doctorate within the next year.

Her position in chemical engineering shares more similarities with Gumina’s female-to-male ratio than Blanchette’s.

“I would say probably a 30/70 split between females and males,” Naglic said. “There’s definitely a lot more males in this field. I’ve been the only female in our group for quite a while.”

Naglic, the doctoral student, doesn’t necessarily see women at a disadvantage in the field of chemical engineering.

But before coming to USC, she attended Midlands Tech in Columbia and had an experience that made her want to prove herself more.

“I went to my first advisement appointment and the advisor asked me what I was wanting to pursue and I told him chemical engineering,” she said. “And he actually laughed. … I did not find that funny.”