By Shayla Nidever and Mary Ramsey

This story is one in a continuing series covering the crisis in public housing in Columbia.

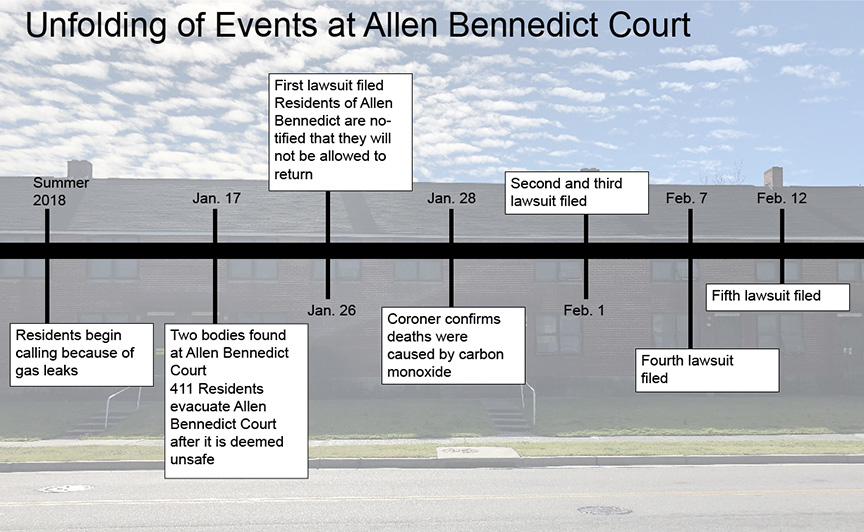

Lavice Goodwin is still adjusting to a new normal after she and more than 400 of her neighbors at Allen Benedict Court were pulled from their apartments following a fatal gas leak last month.

Goodwin, who had lived at the aged Columbia public housing complex for eight years, was evacuated in the middle of the night on Jan. 18, about 18 hours after emergency officials discovered two men dead in separate apartments from carbon monoxide poisoning. Emergency officials swept through the 26 brick buildings at the complex off Read and Harden streets and found 65 apartments in the 244-unit complex with high levels of fatal gases, prompting permanent shutdown of the entire complex.

“It was hell,” she said.

Calling it an issue of “significant public importance,” Columbia Mayor Steve Benjamin, along with Fire Chief Aubrey Jenkins, Police Chief Skip Holbrook, and Columbia Housing Authority executive director Gilbert Walker held a news conference a day later that emphasized the scope of the disaster.

“Based on their work, we’ve determined that this gas leak is not only significant but consistent throughout this property and it is their best judgment and our best judgment, supporting their decision 100 percent, that this property should be closed,” Benjamin said. “We will be closing this property immediately working with the housing authority on relocating the citizens here to safe and suitable housing, some that might eventually be permanent, but certainly temporary housing that these families can live safe and secure.”

When Goodwin evacuated her apartment at 2 a.m., she was told a carbon monoxide detector was reading a level of 3,000 parts per million in her home. That’s enough to kill a person in an hour, according to the National Fire Protection Association. Health effects begin at 10 PPM.

“The whole time, my dog was trying to tell me that something is wrong. Because I asked the veterinarian, why are his eyes staying watery? I know some dogs do that,” she explained. “And he said the whole time, your dog was trying to tell you that you’ve got a gas leak or something … And he said he was trying to tell you you were getting sick. And I stayed sick with upper respiratory infections. I stayed sick.”

Besides the leaks, Goodwin said she had to deal with a variety of issues while living at the pre-World War II complex, including lax maintenance that at times left her without heat or hot water.

“I liked it, and then again I didn’t like it because when we have problems they don’t come and solve the problems. That’s the only thing that I didn’t like about it,” said Goodwin.

After the evacuation, Goodwin was shuffled among three different hotels and didn’t know where her next meal would come from. She missed two weeks of work, and two weeks worth of pay. She had to give away her dog when the veterinarian told her the chihuahua couldn’t survive the stress of moving every few days.

After two weeks of uncertainty, Goodwin was given a HUD voucher to find a new home. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development oversees the housing choice voucher program, which provides rent assistance to low-income residents, elderly and the disabled. Local housing authorities administer the program, matching residents to suitable landlords willing to take the HUD vouchers. Participants must pay 30 percent of their monthly adjusted gross income toward the rent.

Goodwin is now living in an apartment in the North Main area with the help of the voucher, paying less than the $616 a month she was paying when she lived at Allen Benedict. The voucher lets Goodwin live in an apartment not owned by the Columbia Housing Authority while still getting assistance for her rent.

But things still aren’t back to normal.

Goodwin used to live in the same complex as her elderly mother, and she now lives blocks away. Her adult daughter also lived at Allen Benedict before the leaks. Even though Goodwin works as a parking attendant at USC, she’s taking handouts just to get by.

“In a predicament like this it makes me feel ashamed, people coming to me and asking me, ‘what you need?’ And that’s embarrassing,” she said.

Goodwin said she’s grateful for coworkers and supervisors that have been understanding of her situation, but she’s still feeling the effects of missing work.

“Tomorrow is payday, and I ain’t getting no money because I wasn’t here,” she said. “So now I’m gonna have to go back to the housing authority for them to give me some food or something. You know? Because I wasn’t here.”

She said she lost money when trying to find a house of her own through the Columbia Housing Authority, which is facing lawsuits over the deaths and hard questions about how it operated the apartment buildings. Officials told her the money she’d already paid would go towards rent, but Goodwin said that never happened.

“They wasn’t treating us fair, they were really just beating us out of a whole lot of money,” she said.

Maintenance issues were a near-constant struggle, Goodwin said. She spent much of the holiday season without heat, and requests for everything from a clothesline to tree trimming were never met.

“They really wasn’t doing nothing for us,” she said. “I just made it my home because I didn’t have anywhere else to go.”

She added that she would often just do projects, such as repairs to her water heater, on her own. Spending her own time and money on home improvement proved more fruitful than spending day after day asking management to keep their promises.

“They throw us in anything. And when I say anything – anything. Long as it’s a roof over your head, you’ve got to make it your home,” she said. “And it ain’t right. It ain’t right, because when I was paying $616, I should’ve been in a house. Paying that kind of money.”

Now that Goodwin is out of Allen Benedict, she’s learning a new normal. She’s back at work and helping her mother get into an apartment in her new complex or close by using a voucher.

One of the most important parts of getting back on her feet has been reminding herself that others in positions of authority bear responsibility for upending the lives of Allen Benedict residents.

“It’s not our fault. We’re all thinking that we did it, but it’s not our fault. It’s all on housing. It was very stressful to me because it made me feel like I was literally kicked out of my home for not paying rent, but it was a gas leak and it wasn’t my fault,” she said.

“It still made me feel bad because I’ve never been in a predicament like this having to go from pillar to post, once I get comfortable here I gotta pack up and move.”

The Columbia Housing Authority is across the street from public housing complex Allen Benedict Court.

Allen Benedict Court sits empty after residents were evacuated due to gas leaks last month. The buildings will not reopen.

Goodwin recalls that maintenance at Allen Benedict Court took six months to reported to her request for a new window for her apartment.

The story that began when two bodies were found at Allen Benedict Court is ongoing.