Children from Logan Elementary School run and jump on playground equipment during their recess. During the early days of the pandemic, children weren’t able to play together. Photos by Anna Mock

Since the pandemic began in March 2020, those who work with children as counselors and teachers suggest it’s been difficult for children to get the socialization that they need.

Kiaya Demonbreun, a licensed therapist from Columbia, said much of the struggle with children’s mental health is that increased isolation, a finding that is central to the American Academy of Pediatrics’ alarming new report about childhood struggles.

That organization, along with the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Children’s Hospital Association, declared last month that children’s mental health is a “national emergency” due to ongoing stressors from the pandemic.

“Technically speaking it’s a traumatic event, especially mainly with children in regards to the kind of period of isolation when they had to stay at home, get schooling done at home, but then also, limited free time with friends, activities outside of home. It kind of disrupted their whole lives, to be honest,” Demonbreun said.

According to the Oct. 19 declaration from the three organizations, “As health professionals dedicated to the care of children and adolescents, we have witnessed soaring rates of mental health challenges among children, adolescents, and their families over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, exacerbating the situation that existed prior to the pandemic.” The findings showed that the pandemic has intensified the children’s mental health crisis that has been accumulating since 2010.

Although everyone is affected by the pandemic, children with pre-existing mental health concerns are more likely to get hit harder by its effects.

“The kids that are most at risk because of the pandemic are the ones who, before the pandemic, already were struggling with their mental health,” said Schafer, an assistant professor of psychology at University of South Carolina.

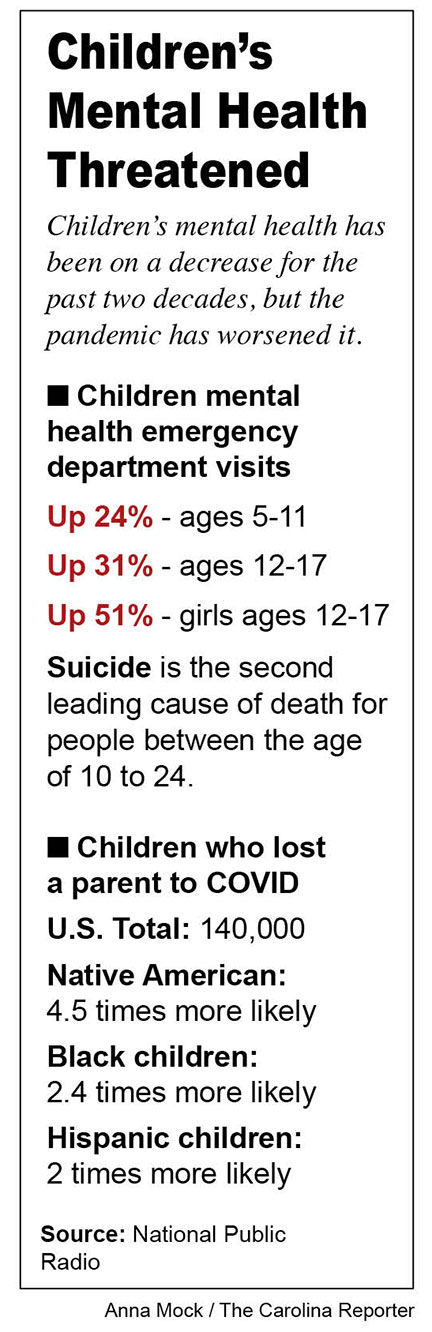

Since the pandemic began, suicide rates have risen 24% for children ages 5-11 and 31% for ages 11-17, according to NPR. Schafer thinks harmful content on social media could be a contributing factor to this increase.

“With the advent of access to unfiltered internet at all times, and social media apps that are using algorithms to take kids sometimes down dark pathways, it may be giving kids exposure to more content that’s more violent or self-harming,” Schafer said.

Parents during the pandemic have often faced stress from job insecurity or financial trouble, which in turn affects their children.

“Obviously, as kids get older, they’re more capable of understanding and processing parental feelings. But when kids are small, they really need to be shielded from the stress, financial stress, you know, employment stress, the kind of things that kids have zero control over because it will make them feel helpless,” Schafer said.

The financial stress can also prevent kids from accessing therapy. Jessica Pena-Cabana, a licensed professional counselor in Columbia, recommends policymakers implement financial programs to cover mental health services.

“Parents won’t bring them, because they can’t pay for it, or their insurance won’t cover it or the co-pay’s too high,” Pena-Cabana said.

Another barrier to help is a shortage of therapists. As of March 31, 2021, about 37% of the American population was living in an area with a shortage of mental health professionals. South Carolina ranks higher than the national average, with 44% of its population experiencing a shortage, according to U.S. News.

“One of the things that is a concern right now is there is a real shortage of mental health workers. That real shortage is not just something we see on the national news. It’s one that we’re experiencing here in South Carolina,” said Toni Campbell, lead coordinator for school counseling services in Richland One.

Although the pandemic brought it to the forefront, children’s mental health is not a new issue. According to Schafer, children’s mental health has been an epidemic for the past two decades due the impact of evolving technology.

“Children were kind of given more access, you know, to internet, more access to video gaming systems, more access to all these things that are taking them away from human interaction … that is really detrimental to emotional regulation and like, positive social development,” Schafer said.

Although these are challenging times, Schafer has hope that kids will be able to bounce back with adequate support.

“Kids really are resilient and capable, but parents and caregivers are the primary function of how they fare afterwards,” Schafer said.

As for what exactly parents can do to help, Schafer recommends limiting screen time and prioritizing face-to-face interaction within the family.

“Have dinner together, have conversations, have family game night, things that are where parents and children are looking into each other’s eyes and having conversation. Being able to hear your kid’s feelings, being able to respond, and be compassionate and be present,” Schafer said.

Toni Campbell, lead coordinator for school counseling services in Richland One, is concerned about the changes she’s seen in children’s mental health. “For lack of a better term, a perfect storm of things have occurred,” Campbell said.

Richland One’s Lyon Street Services Center is one of the facilities Campbell works in, providing counseling to students within the school district.

Emily Schafer is a former therapist who now teaches psychology classes at University of South Carolina’s Union campus. She believes that children are resilient and adequate support from parents will help them overcome mental health issues. Photo courtesy of Emily Schafer